Damaged park will show off restoration

LESTERVILLE, Mo. -- On Dec. 14, Kimberly Burfield's dream job became a nightmare. But Burfield, who at the time was assistant superintendent of Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park, didn't take much time for personal disappointment. She dived into the job of rebuilding the park after 1.3 billion gallons of water crashed from nearby Proffit Mountain, devastating the park and wiping out the home of her boss, Jerry Toops, and his family...

~ More than 14,800 truckloads of debris have been carted out of Johnson's Shut-Ins.

LESTERVILLE, Mo. -- On Dec. 14, Kimberly Burfield's dream job became a nightmare.

But Burfield, who at the time was assistant superintendent of Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park, didn't take much time for personal disappointment. She dived into the job of rebuilding the park after 1.3 billion gallons of water crashed from nearby Proffit Mountain, devastating the park and wiping out the home of her boss, Jerry Toops, and his family.

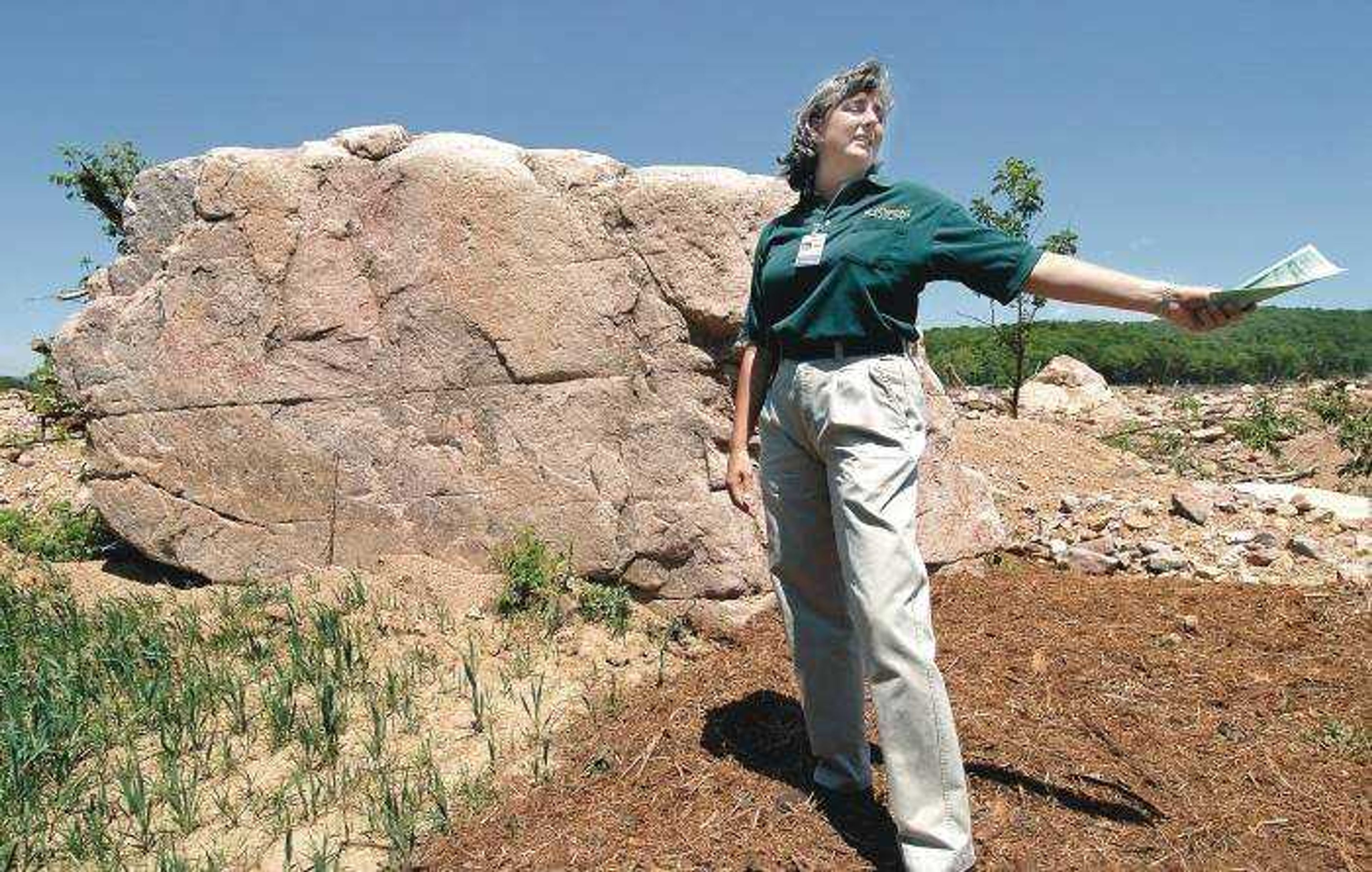

Now Burfield is the superintendent of the state park, which is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the state system. And she's getting ready to welcome visitors back Saturday to show them how much restoration work has been accomplished. The park will open at 8 a.m., closing at 7 p.m.

"We don't know what to expect" in terms of crowds, Burfield said while leading a pack of reporters and photographers on a preview tour. "We'll be managing it as we would any other day. We may have everybody, and we are prepared for everybody."

On the morning of Dec. 14, the wall of the AmerenUE reservoir atop Proffit Mountain collapsed. The reservoir, which fed a hydroelectric generating plant, released a torrent that scraped bare the mountainside, denuded the valley below and left a mix of sand, gravel and boulders as much as eight feet deep covering some of the main user areas of the park.

An independent consultant's report released Thursday by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission confirmed that the broken water gauges in the reservoir led to the reservoir being overfilled. Water washed over the top of the earth-and-rock wall, eroding it until it collapsed.

Burfield had been in her job less than six months. Hired in July, she holds a master's degree in geology, an interest inspired by a visit to the park with her mother 23 years ago. Her mother was a geology student at the time, she said.

"My first visit here set my path in life," Burfield said. "I went to college, got a degree, and it took me 23 years to find my way home."

Before the reservoir collapsed, Burfield knew Toops planned to take another job in the state park system. And she was eager for the promotion that would put her in charge of the park that inspired her life's work.

The catastrophe only strengthened her desire for the job, she said. "I wanted it before, and I wanted it after. It gave me even more drive to be a part of the team to get it back."

Despite her short time with the park sytem, state parks director Doug Eiken said Burfield proved she is ready. "We couldn't get a better person than her right now," he said. "We've got a lot of confidence in her."

The restoration has been a huge effort, starting with the staggering amounts of debris that had to be removed. According to figures provided Thursday, crews have mulched and removed approximately 122,000 cubic yards of woody debris. Another 6,000 cubic yards of silt have been trucked out of the park.

In all, more than 14,800 truckloads have been carted out of the park.

The cost of the damages is being borne by AmerenUE, which has estimated that the company will spend $53 milion to $73 million.

The east fork of the Black River now runs clear through the shut-ins, where for weeks after the collapse of AmerenUE reservoir atop Proffit Mountain it ran gray with silt. Parking areas have been restored, the park store is ready for business and interpretative signs have been installed near the popular shut-ins and along an auto tour route for visitors.

Two things have changed for visitors this year -- no one can play in the water as it courses over the billion-year-old rocks of the shut-ins and no one can camp in the park.

The water isn't safe, said Greg Combs, district supervisor for state parks in eastern Missouri. Every time substantial rain moves through the area, he said, more debris is dislodged.

Rains Wednesday night and early Thursday left a four-foot piece of iron reinforcing bar lodged in the middle of the Black River. And in a pool just downstream from the shut-ins, the water level is down more than 10 feet from last year and divers have found sunken trees lodged in silt.

"We have to assume there may still be more hazards out there," Combs said.

Areas barred to visitors are clearly marked, both with signs and a chain-link fence stretches across most of the park.

The massive debris removal effort included bulldozers and giant mulching machines. But in one sensitive area, the debris removal involved shovels and hand-guided vacuums as workers sought to save a wetlands area.

The area known as a fen has cool, spring-fed water percolating up through the rocks. Rare plants that are survivors from the ice age dominated the fen before the disaster.

Johnson's Shut-Ins has more plant diversity than any other state park, said Ken McCarty, chief of the Natural Resources Management Section of the Division of State Parks. Approximately 20 percent of those species were in the fen.

The fen had to be saved before the growing season, and McCarty hopes enough was accomplished. "We had to do it in a way that the plants weren't trampled or squished," he said. "We had 20 to 30 people in here with wheelbarrows and shovels."

Not all the debris has been removed. A field of boulders surrounded by sand, silt and small stones has been left in place. In front, a plaque describes the scene of "The day that changed Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park."

"The air is damp and cold with a heavy mist. The sun will rise over the mountains in about two hours. From the top of Proffit Mountain to the east, you hear a rumble louder than any thunder and then a roaring sound like a giant freight train coming straight at you."

Visitors will be welcome to walk a trail out into the boulder field and take a close look at the massive stones, many too heavy to be removed with the equipment on hand. One six-foot-tall boulder at the edge of the field is munger granite, Burfield said to the assembled reporters, and it traveled well over a mile from the top of Proffit Mountain.

Despite the restrictions on uses of the park, Burfield said she hopes visitors will be pleased with what they see. "I hope they see that we have made a lot of progress," she said. "This is only the first stage in creating a new park."

rkeller@semissourian.com

335-6611, extension 126

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.