Central faces troubling statistic with black graduation rate

Central graduates less than 60 percent of its black students, according to the latest school district report card from the state's education agency. In contrast, 85 percent of white students in the class of 2006 graduated last spring. Statewide, the black graduation rate in 2006 was 75.9 percent...

Central graduates less than 60 percent of its black students, according to the latest school district report card from the state's education agency. In contrast, 85 percent of white students in the class of 2006 graduated last spring.

Statewide, the black graduation rate in 2006 was 75.9 percent.

Both Lands and Hill recently enrolled at the district's Alternative Education Center to finish their coursework and earn high school diplomas. Their personal ordeals are just two of the stories behind the troubling statistics.

Lands attended Central High School her freshman and sophomore years before dropping out and moving to New Madrid, Mo., with her boyfriend. "A lot of kids drop out because they don't do well in school," she said.

Grades weren't her problem, though. She said she got mostly A's and B's. Lands said she dropped out because of conditions at home. Her mother's boyfriend and his friends were around the house a lot. Lands said she had no privacy. "I had to sleep in the front room."

A year and a half after dropping out, she has returned to Cape Girardeau and to school. Now 17 and living with her aunt, Lands hopes to earn her diploma by October.

She has career plans. "I want to model and have my own clothing line and do some interior design work," said Lands, her hair braided tightly with strands of red and white yarn.

Many girls drop out after becoming pregnant. Others just aren't motivated to stay in school. "They don't want to put in the effort to get up early five days a week," Lands said.

Ultimately, she said, school administrators and teachers can't force students to attend school. At age 16, students can legally drop out. "I think it is all up to the students," she said.

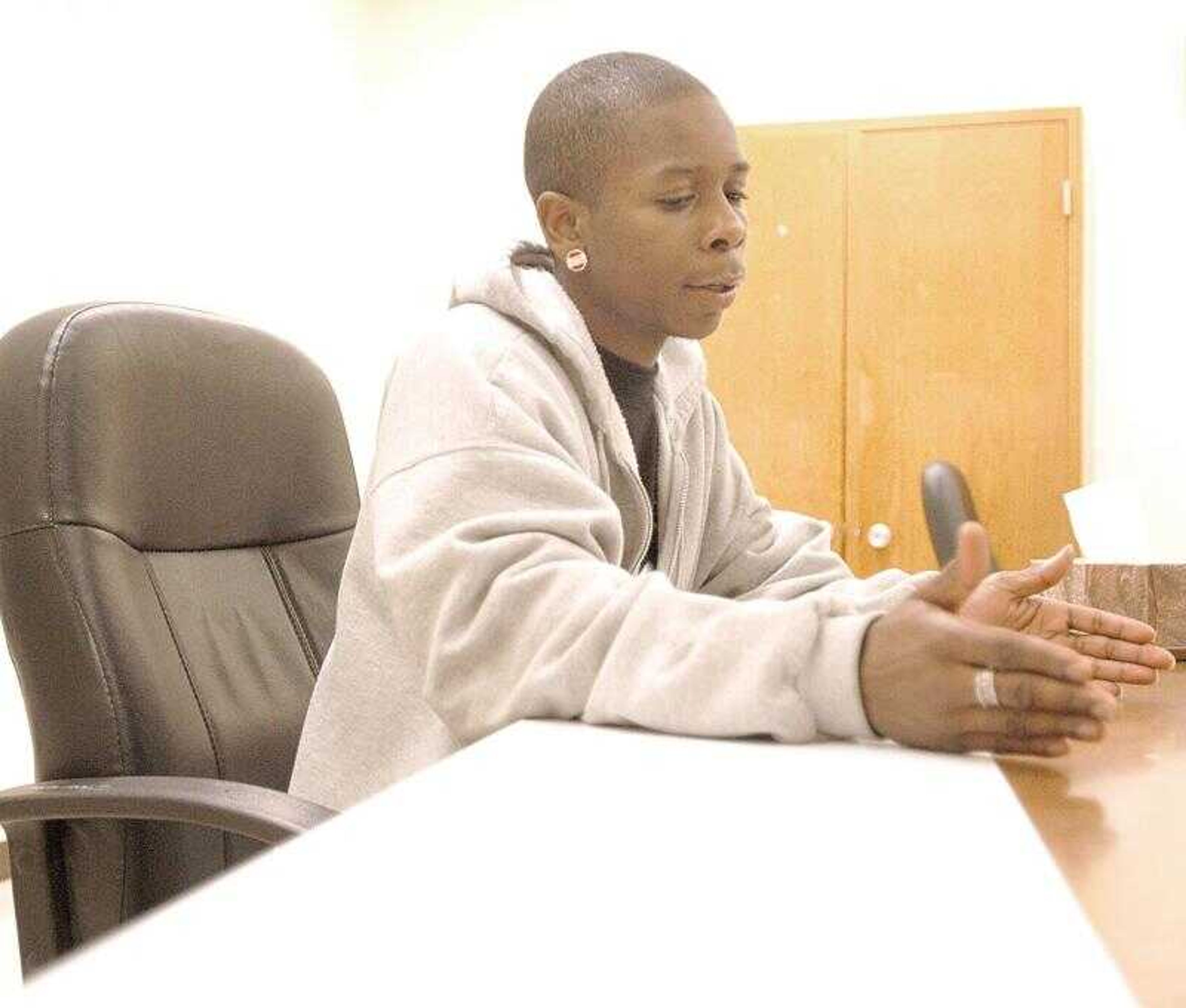

Hill, 18, said he was close to finishing his junior year at Central when his poor attitude led him to quit school. He said he acted badly to get attention.

"I would get mad at teachers. I never wanted to listen. I was hard-headed," he said.

He moved to Colorado and worked in construction. But after fathering a child, Hill decided he needed to get an education and be a better role model for his daughter, who is almost a year old.

He began attending classes at the alternative center earlier this month.

"I plan on going to college and getting a decent job and at least make a decent living," he said.

Hill said many black students find it hard to get through high school because they grow up in southside neighborhoods where drug use and drug dealing are common. "It's basically peer pressure," he said. "You just have to walk against that wind."

While Central's black graduation rate of 59.3 percent is well below the 74.4 percent rate at which black students graduated in 2003, it's nearly 5 percentage points higher than the black graduation rate at the school in 2005.

Central isn't alone in its low graduation rate for black students. Nationwide, only 51 percent of black students graduate from high school.

Black females graduate at a higher rate than black males, 57.8 percent compared to 44.3 percent, according to the Editorial Projects in Education Research Center based in the Washington, D.C., area.

Cape Girardeau school officials have no immediate answers to boosting the graduation rate among black students.

Cape Girardeau School District assistant superintendent Pat Fanger pointed out that the dropout rate among black students declined last year in the district. Only seven students dropped out compared to 35 the previous year.

But the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education calculates the graduation rate on the basis of each graduating class. That takes into account students who first entered high school four years earlier and those who subsequently dropped out.

On that basis, 22 black students failed to graduate in 2006. Thirty-two black students graduated, state statistics show.

Fanger said the district is working to implement a parent liaison program in all its school buildings. The program is already in place in Franklin and Jefferson elementary schools and at Central Middle School.

Each of those three schools has a liaison who works with parents to address their questions and concerns and encourage more parental involvement.

Hill thinks the high school needs to provide more tutoring and hands-on guidance for students at risk of dropping out after their freshman year. High school principal Dr. Mike Cowan said that's something to consider. But he said the high school staff has focused more on helping freshmen for a reason.

"That is where we lose the majority of our children," he said. Students who don't pass enough courses to be classified as sophomores in many cases end up dropping out.

"There is a strong identity for children to want to be graduated with their class," Cowan said. "Once they get so far off track and realize they won't be able to graduate with their class, suddenly graduation loses its magnetic pull for some children."

Some students leave school for a paycheck at a minimum-wage job, he said.

Poverty, he said, is also a factor. Research on a national level shows that many dropouts come from low-income families. Nationwide, high school students living in low-income families dropped out of school at nearly six times the rate of students from higher-income families, according to a 2004 report from the National Center for Education Statistics.

In 2001, eleven percent of high school students from low-income families dropped out nationwide. At the same time, only 5 percent of middle-income students and 2 percent of students from wealthy families dropped out of school, the education statistics center reported.

The number of low-income students at Central High School has been growing, Cowan said. Nearly 38 percent of Central High School students were eligible for free or reduced-price school lunches in the 2005-2006 school year, state statistics show. That's up from 23.6 percent in the 2001-2002 school year.

Many dropouts have parents who themselves dropped out of high school, Cowan said. "If the mother is a high-school dropout, the likelihood that the student will be a high-school dropout greatly increases."

Parents who are dropouts often are reluctant to talk to teachers or get involved in school life, he said.

Fanger said the district hopes to expand the parent liaison program to all schools in the district by August, but that depends on securing federal grant money to fund the positions.

A parent liaison program at the high school might improve the graduation rate but won't solve the problem, she said. "I don't think there will be any one magic solution."

mbliss@semissourian.com

335-6611, extension 123

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.