'The Lives They Left Behind'

NEW YORK -- One left a starter pistol and a blue suit jacket, barely worn. Another left a lace-trimmed christening gown, probably made for an infant daughter who died. The artifacts, part of an exhibit opening Monday at the New York Public Library, were culled from 400 suitcases left behind by patients at the Willard Psychiatric Center in upstate New York, which closed in 1995...

NEW YORK -- One left a starter pistol and a blue suit jacket, barely worn. Another left a lace-trimmed christening gown, probably made for an infant daughter who died.

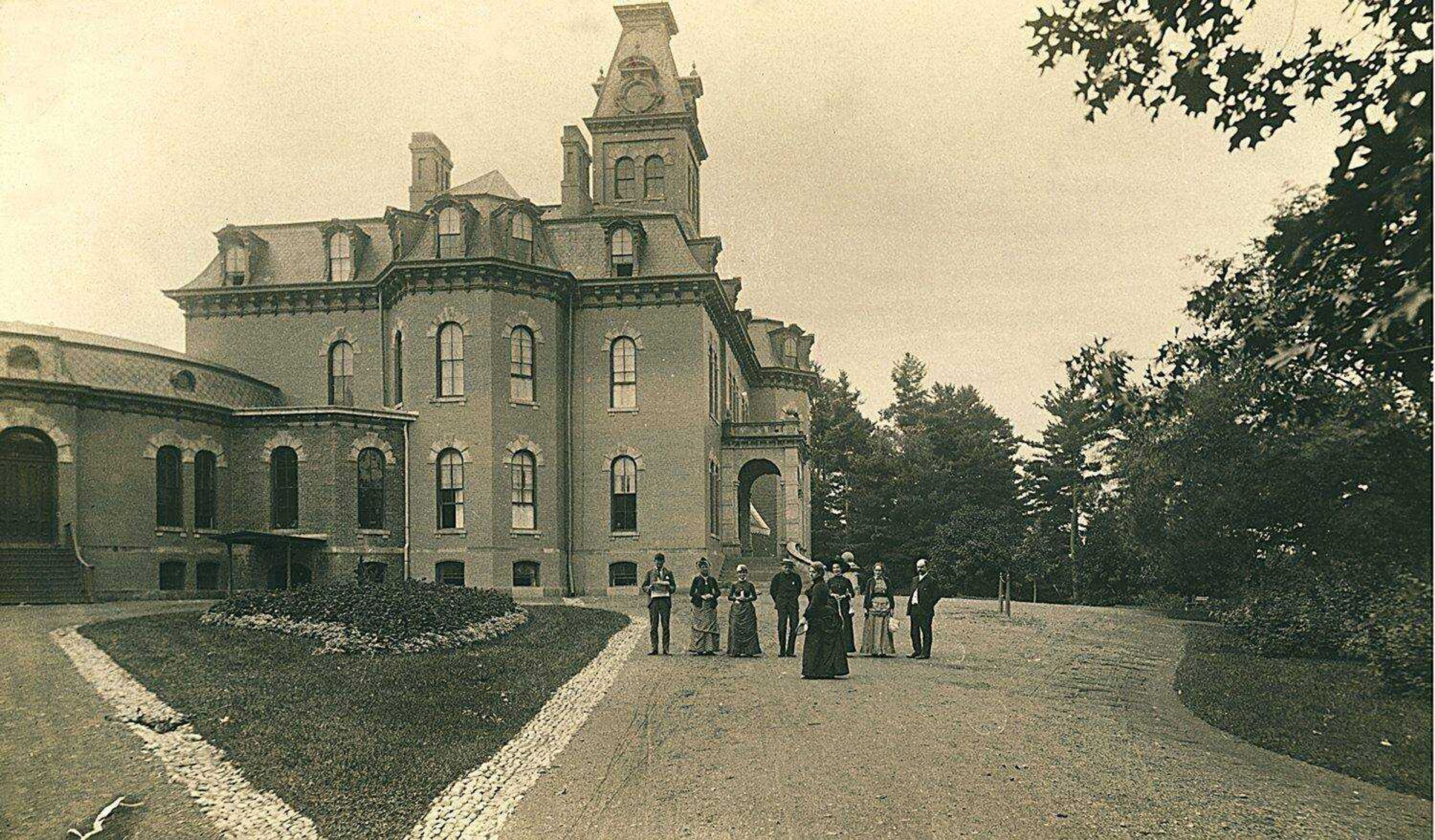

The artifacts, part of an exhibit opening Monday at the New York Public Library, were culled from 400 suitcases left behind by patients at the Willard Psychiatric Center in upstate New York, which closed in 1995.

The exhibit sheds light on the little-known world of patients who spent decades at the state institution for the insane, arriving with their belongings and in most cases never leaving.

"There were one or two people who had access to their belongings somehow over the years. But most of them never saw their stuff again," said Dr. Peter Stastny, a psychiatrist who is an organizer of the exhibit and co-author of an upcoming book, "The Lives They Left Behind: Suitcases From a State Hospital Attic."

Formerly known as the Willard Asylum for the Insane, the hospital opened in 1869 in the Finger Lakes region -- about 300 miles northwest of New York City -- and closed 126 years later as part of the nationwide move toward de-institutionalization of psychiatric patients.

'Warehousing people'

"It was started as the state's hospital for people who were considered hopeless," said Darby Penney, a former state mental health official and the other author of the book about the artifacts, due out in January from Bellevue Literary Press.

"They weren't trying to help anybody get better," Penney said. "They were warehousing people and they tried to do it as cheaply as possible."

The exhibit -- on display through Jan. 31 at the library's science, industry and business branch on Madison Avenue -- features artifacts from just three of the suitcases found in an abandoned attic at Willard plus information about 10 former patients, the same 10 profiled in the book.

Stastny and Penney received permission to view medical records of the patients they chose to focus on in order to tell their stories. None of the patients is alive, but they were given pseudonymous last names in the book and are identified only by first names in the exhibit.

Patients landed in the mental-health system for various reasons -- they drank too much, they heard voices, they despaired after a loved one died.

Frank and Ethel

Frank, a natty dresser whose suitcase contained the jacket and starter pistol, was an Army veteran who made a scene when he was served a meal on a chipped plate at a Brooklyn restaurant in 1945.

"I thought that someone planned to kill me," he told a doctor at Kings County Hospital.

Frank arrived at Willard nine months after the restaurant incident and was deemed incurably insane. He was transferred to the VA system, where he died in 1986 after spending more than 40 years in institutions.

Ethel's suitcase contained the christening gown along with booties, a knitted baby bonnet and six silver spoons.

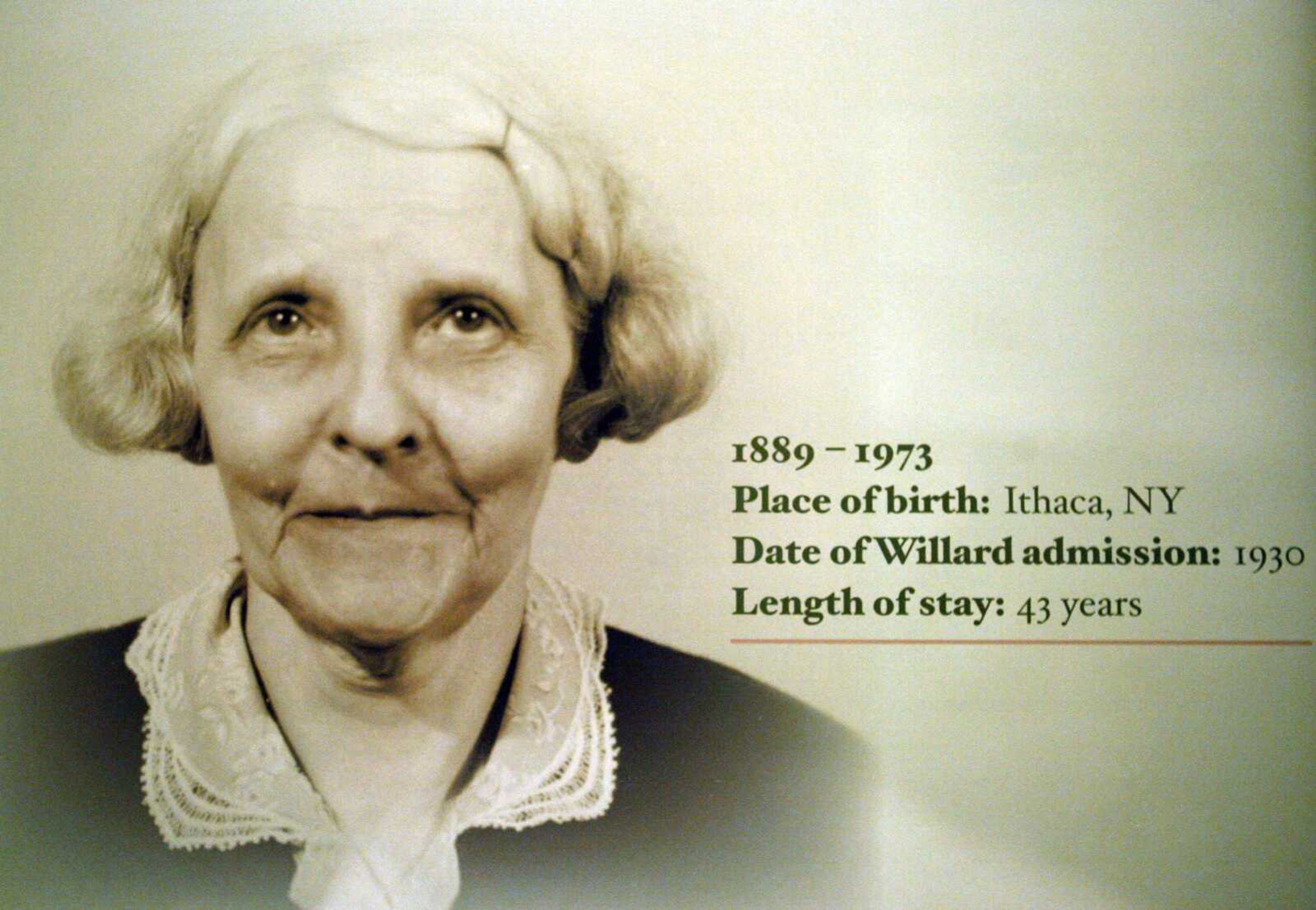

Ethel was 40 when her marriage to an abusive husband ended in 1930. She had two living children; two daughters had died in infancy. Her landlady in the village of Freeville told authorities that she had heard Ethel laughing in the middle of the night and that Ethel "constantly consulted the spirits about where she should go and what she should do."

Ethel denied the landlady's accusations and said the two had quarreled over money, but she was committed to Willard and died there in 1973.

Willard housed more than 3,000 patients during its fullest years, from 1910 to 1920, Penney said. It was a small city that ran on the unpaid labor of patients who grew food, made clothing and shoes, and worked in the slaughterhouse, brickworks and blacksmith's shop.

That practice ended after 1973 when courts ruled that patients at institutions were covered by the Fair Labor and Standards Act and could not be forced to work for free.

The exhibit is sponsored by the library, the city Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

Wendy Brennan, executive director of the alliance's New York City metro chapter, said she reacted emotionally to the artifacts.

"We pass people by on the street all the time who are ill, and we don't pay attention to them," she said. "And you can't do that."

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.