Finding the lost boys: Author talks about book on history of homeless boys in St. Louis

Some ideas come and go, but for Bonnie Stepenoff, the idea of a book shining light on the forgotten and misused youth of midcentury St. Louis came in the 1970s and has finally gone to print. Her fifth book, "The Dead End Kids of St. Louis: Homeless Boys and the People Who Tried to Save Them," details the lives of young boys trying to survive in a city that did not have the resources to help them...

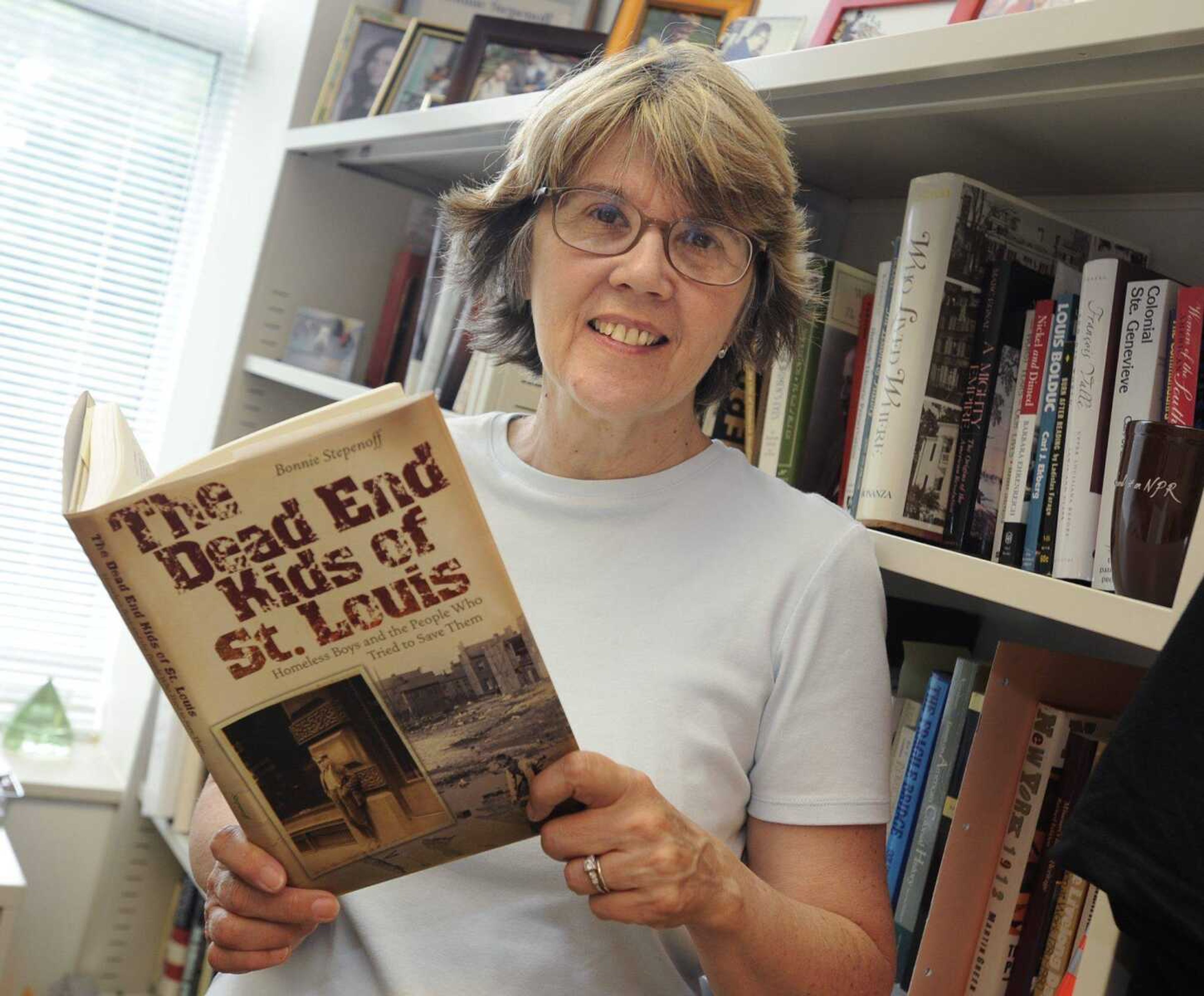

Some ideas come and go, but for Bonnie Stepenoff, the idea of a book shining light on the forgotten and misused youth of midcentury St. Louis came in the 1970s and has finally gone to print. Her fifth book, "The Dead End Kids of St. Louis: Homeless Boys and the People Who Tried to Save Them," details the lives of young boys trying to survive in a city that did not have the resources to help them.

Stepenoff, a history professor at Southeast Missouri State University, volunteers at the Cape River Heritage Museum and lives in Cape Girardeau with her husband, Jerry, and her dog and cat. She answered a few questions from SE Live about her latest tome and her plans from here.

SE Live: How does "The Dead End Kids of St. Louis" differ from your other books?

Bonnie Stepenoff: Well, my first book was about girls. I wrote about girls and young women who worked in the silk mills in Pennsylvania, where I grew up. My other four books have been about Missouri, although the topics are very different. This new one is about the boys who spent their days and nights in the streets of St. Louis, working as messengers, selling newspapers, begging, gambling, getting into trouble with the law and sleeping in vacant lots, lumber yards and even in caves. It covers the period from 1860 to 1960, a long time span, with a lot of changes, but the problem of these homeless boys did not go away, even though a lot of people tried to help them.

SEL: How long did the research take for this one?

Stepenoff: My research on this really began in the late 1970s, when I was working at the State Historical Society and browsing in their book collection. I found a book called "A Tour of St. Louis" that was all about the dark side, the down side, of the city's life. There was a section in it about the boys who wandered the streets, eking out a living and sleeping wherever they could find shelter. Between then and now I worked on a lot of other things, but I kept thinking about this topic. In 2006 I spent a semester teaching in the Missouri London Program, and I had a chance to poke around in London's museums and libraries. I learned that the problem of homeless boys was common to industrial cities. Oliver Twist and the Artful Dodger were fictional characters, but they represented thousands of real boys who drifted through the London streets. And there were boys like them in St. Louis, too.

SEL: Were there times when you thought the research would never end?

Stepenoff: For a long time I thought that I would not be able to find enough information about these boys, who lived under the radar. I spent a lot of hours reading microfilmed copies of old St. Louis newspapers. Anybody who does historical research will tell you that can be tedious. Just ask my students. But then there were breakthroughs. An archivist at the Missouri Historical Society in St. Louis pointed me to the journals of the House of Refuge, which listed the names of hundreds of boys, and a much smaller number of girls, who had been committed to that grim facility between 1854 and 1899. The journal told why they had been committed and what happened to them when they were released. Some were "indentured" as apprentices. Some went to hospitals or the poor house. Some escaped. Some ended up in adult prisons. There were lots of stories there.

SEL: What did you find out that surprised you?

Stepenoff: Lots of things surprised me. One thing I learned was that the romanticized picture we have of hobos riding the rails during the Great Depression is way off the mark. Climbing onto freight trains was dangerous and caused a lot of boys and young men to die or lose limbs. A startling number of the people riding the rails were very young and easily preyed upon by older men.

SEL: What are you working on next?

Stepenoff: Well, this summer I am stomping about the streets of Ste. Genevieve, helping the Midwest office of the National Park Service put together a report on properties there that have national significance in connection with French exploration and settlement. After that, who knows?

SEL: The book is about lost boys. Were there no lost girls?

Stepenoff: There were girls who ended up in the streets, and their stories are worth telling, but they are different from the stories of the boys. Boys overwhelmingly outnumbered girls in reformatories. Far more boys than girls picked up and left home and rode the rails. Hobo jungles, for instance, were exclusively male environments.

SEL: As a woman, was it hard to give voice to boys, especially boys who lived generations before you?

Stepenoff: I am a mother of two daughters, but now I have a grandson; so finally I can observe a boy growing up. One thing that helped me to give voice to boys who grow up in previous generations was the fact that several famous men emerged from the street life of St. Louis. Some of them wrote autobiographies. Others had biographies written about them. Archie Moore was one of them. So was Sonny Liston. Both of them became famous as boxers. William S. Burroughs was not a homeless boy or a street kid, but he wrote nostalgically about Skid Row in St. Louis. I spoke with the daughter of a boy who had been sent to several orphanages and ran away from all of them, and she told me how his early experiences had made it hard for him to be a family man, even though he grew up to be successful in business.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.