Ben Rushin, teenager with autism, shattered expectations and will graduate Thursday

I hadn't talked to Ben Rushin for more than a passing hello since 2004, when he was just a 10-year-old boy. He was the protagonist in one of the best stories I'd ever written; more specifically, I co-wrote the four-part series with Callie Clark before she became Callie Clark-Miller, years before we had two sons, both of whom have had speech delays like Ben...

I hadn't talked to Ben Rushin for more than a passing hello since 2004, when he was just a 10-year-old boy.

He was the protagonist in one of the best stories I'd ever written; more specifically, I co-wrote the four-part series with Callie Clark before she became Callie Clark-Miller, years before we had two sons, both of whom have had speech delays like Ben.

When I last reported on Ben, he had just won a youth wrestling tournament, such an incredible accomplishment for a boy who suddenly stopped talking for two years and had significant problems with motor skills. During most of his boyhood, he had trouble running. Didn't learn to tie his shoes until a few months before he won the tournament. Significant speech issues. In essence, at 10, he had already gone toe-to-toe with autism, absorbed some blows, punched back, persevered and emerged a champ. The wrestling tournament wasn't necessarily the story. The back story was the story. Ben went through hundreds upon hundreds of hours of various types of therapy before he attended school. The story eight years ago was more or less a story about his parents, Richard and Debby, who were desperate to hear their son's voice. Parents who didn't tell the school about the diagnosis because they would not let autism define their son.

Ben will graduate from high school Thursday. The boy I remembered is a man now, some six feet tall, about 200 pounds, sporting a well-groomed beard with no mustache. A handsome, athletic teenager. Confident. Sure of his strengths and aware of his shortcomings.

I casually followed Ben Rushin the athlete in our newspaper over the years. I saw a mention here and there of an athletic accomplishment; he played three sports in high school: football, wrestling and track, where the shot put was his specialty. He lettered four years in every sport except football, where he lettered beginning his sophomore year.

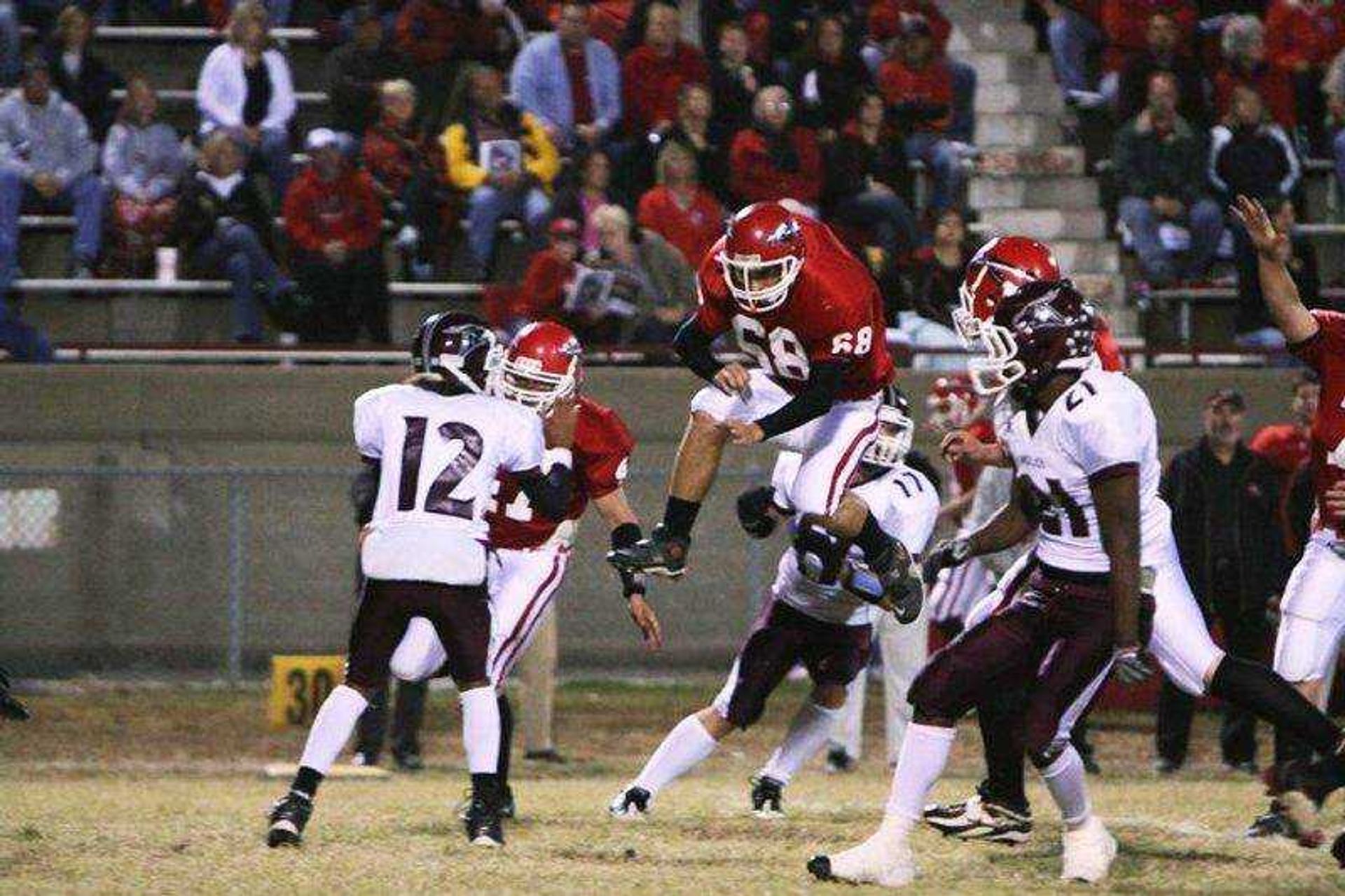

I watched Ben play live in the Jackson vs. Central football game last fall. He was relentless. Undersized at roughly 215 pounds, the nose tackle was all over the field, making sacks, pressuring the quarterback, living up to his nickname, Triple-B, for "Big, Bad Ben." He even recovered the onside kick late in the game that gave the team a chance to win. He was a crowd favorite, there was no question. But I didn't realize the totality of his athletic accomplishments until he listed them for me.

* Football team co-captain

* Second team all-conference, football

* First team all-region, football

* Wrestling team, co-captain

* Conference champ, wrestling

* State qualifier, wrestling (38-9 record, senior year)

* Conference champ, shot put

* State qualifier, shot put

Like his wrestling tournament as a 10-year-old, his list of athletic accomplishments isn't the story. Ben Rushin is not the best athlete Jackson has ever seen. He isn't the fastest or the strongest. He's not a blue-chip recruit. Ben's story is not about the climax; it's the rising action detailed by his painstaking desire to crush his own natural limitations. In a world where there's an excuse for everything -- so as to not have to do anything -- Ben Rushin has half-nelsoned his potential and pinned it the mat. To Ben, potential has never been something to meet. It is to be conquered.

"You have to tell him when to stop, because he'll just keep going," said Steve Wachter, wrestling and track coach. "In practice, I'm telling you it's full go, it's go till he can't go no more. There's no half-speed with Ben."

Eight years ago, Ben was this passionate bundle of energy. He slurred some words a bit, and was at times difficult to understand. His enunciation is much clearer now, but he still talks fast, as though his competitive nature spills over and nothing less than full throttle is acceptable.

For someone who didn't talk from ages 2 to 4, Ben Rushin has a lot to say now.

He's known for giving inspirational half-time speeches in the locker room. He likes talking in front of people, though he admits his grammar in the written word is an academic weakness. He made the honor roll for this first time in a few years last semester. He still requires a bit more time for test-taking; the physical act of writing is still a challenge.

He scored a 21 on his ACT, which is about average; however, he scored an impressive 27 on the mathematics portion of the test. He says he wants to be a special needs or elementary schoolteacher. He says he's had some great teachers who have really helped him over the years. He wants to be like that.

His prospects for college are good; he's looking into a track scholarship offer at a junior college in the Kansas City area, where he thinks it will be pretty cool to live in an apartment.

A lot of people who meet Ben don't realize he was diagnosed with autism as a young boy. There are subtleties that can be identified if a person knows what to look for. He speaks with a certain unemotional, matter-of-factness that could be mistaken for arrogance. Sometimes his language sounds a bit scripted, as he pulls quotes from movies or TV shows to answer questions, all done in the appropriate context.

In so many more ways, Ben seems so very un-autistic.

An extrovert, he has a way of engaging people in conversations, developing relationships with friends across the state. He says he has friends in all circles of high school life, and doesn't believe in cliques. He doesn't judge, he says. He sticks up for people who are being bullied. He's in a service club for teens; he's helped coach younger athletes, and he's very philosophical. He was voted homecoming king. He has 1,400 friends on Facebook.

It's clear that Ben missed the memo that autistic teenagers aren't supposed to be highly sociable.

Wachter said sports captains are voted on by the team. He said the school as a whole has embraced him.

"His attitude is so positive," Wachter said. "He's very considerate of others all the time. They just know who Ben is, what he stands for and what he does. Ben's very likable, and Jackson, though it's a big school, it's tight-knit; the students know him, know his heart and know where he comes from. They like Ben a lot. They understand Ben is so good-hearted. There's no fake to Ben. What you see is what you get. I think kids see that in him."

Ben's older sister Rachel astutely points out that Ben was not a borderline autistic as a young boy. Rachel hears that a lot. "Well, given the way he is now, he must not have been that bad," they say.

Ben Rushin couldn't talk when he was 4 years old. This was a child who would bang his head against the wall and punch himself. This was a child who couldn't tell his parents that he had cut his foot. This was a boy who did not flinch when firecrackers went off at his feet. This was a boy who fell off a slide, nearly snapped his arm in two and didn't cry. His hurdles were huge. Diagnosed with Pervasive Developmental Disorder on the autism spectrum, Ben Rushin could have gone many different ways. And therein lies the message from the Rushin family to any parent dealing with a new diagnosis. Stay positive. Keep fighting. Keep pushing. Never settle. If Ben can do it, your child could, too.

I asked Triple-B why he turned out so well given his childhood challenges, where he learned to be so tenacious, and Ben gave the credit to his mother. Debby, a schoolteacher at Oak Ridge, approached her son's development in much the same way Ben approached sports. Dad was the athlete and softhearted toward his son, but it was Mom who stubbornly, insistently kept pushing Ben to improve and engage. Whatever it took.

On Thursday, Ben Rushin will graduate high school. It will be an emotional time for Richard, Debby, Ben's two sisters and younger brother. But for Ben, it will be another milestone, just another thing to add to the list.

There's all new potential out there now that high school's behind him. Ben's got a lot more pummeling to do.

Bob Miller is the editor of the Southeast Missourian. He can be reached at bmiller@semissourian.com

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.