OMG: Social media may wreck your kid's writing

The prevalence of Facebook, Twitter and texting has all but obliterated punctuation, capitalization and apostrophes in schools, threatening the future of formal writing, educators say. And it's no wonder. Cape Girardeau public school students, for example, start learning keyboarding in kindergarten to get them used to technology, curriculum coordinator Theresa Hinkebein said. But she noted kindergartners already know how to operate smartphones and have computers at home...

The prevalence of Facebook, Twitter and texting has all but obliterated punctuation, capitalization and apostrophes in schools, threatening the future of formal writing, educators say.

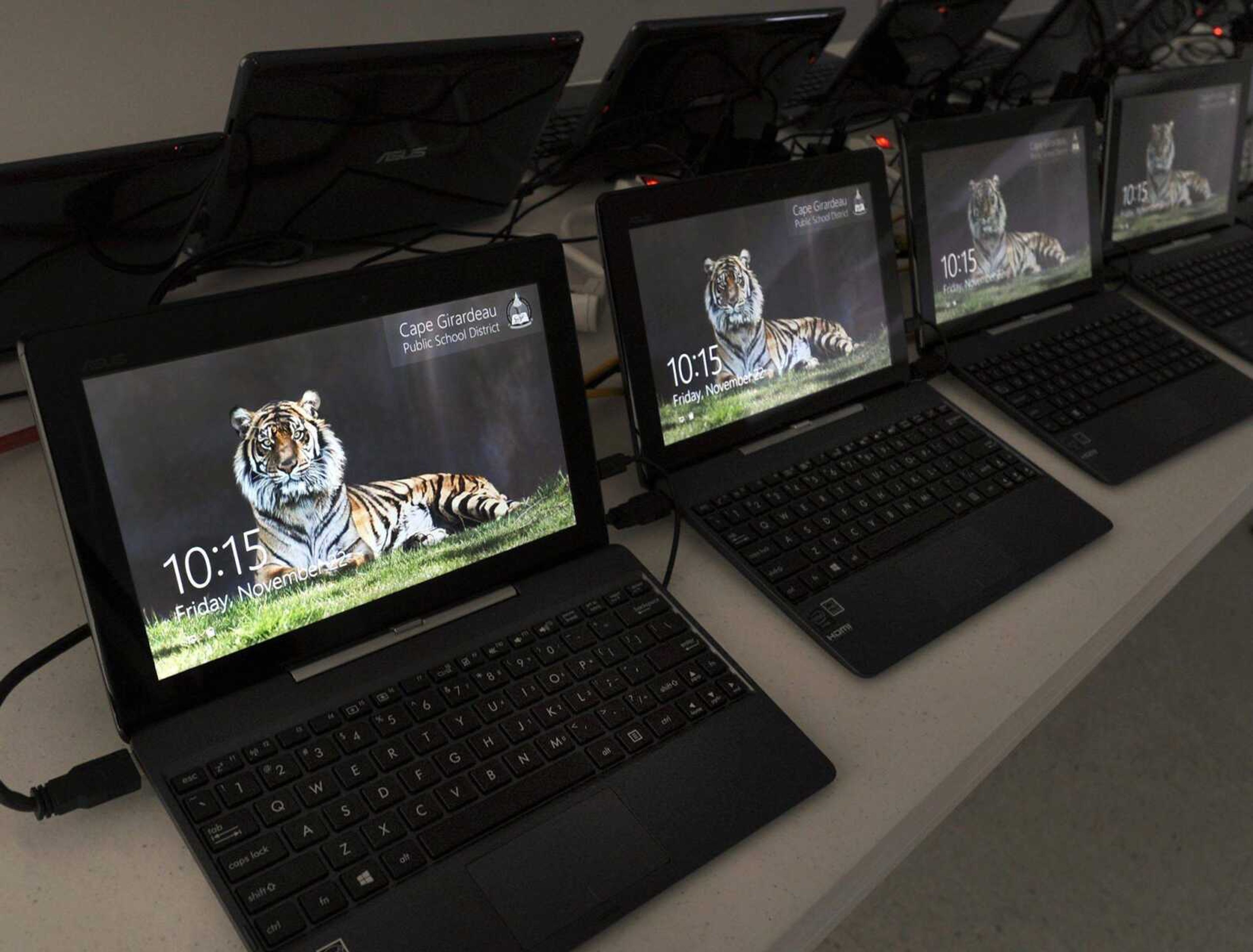

And it's no wonder. Cape Girardeau public school students, for example, start learning keyboarding in kindergarten to get them used to technology, curriculum coordinator Theresa Hinkebein said. But she noted kindergartners already know how to operate smartphones and have computers at home.

Keyboarding itself doesn't have an effect on grammar and formal writing, but with people relying more on electronic devices, physical handwriting also is disappearing.

Hinkebein said students are taught cursive writing the second semester of second grade, and kindergarten through 12th-grade students are taught when it's inappropriate to use informal language.

"Our teachers really try to help our students understand the difference between formal and informal writing," she said.

But students come to school "already immersed in technology," Hinkebein noted.

Assistant superintendent for academic services Sherry Copeland said though spell-check and grammar software exist, students still need to know how to spell and use correct grammar. Copeland said she has been on job interviews where a prospective employer has asked her to sit down and write something longhand.

Southeast Missouri State University writing instructor Eric Sentell said in an email to the Southeast Missourian that since he began teaching six years ago, he's noticed a difference in the quality of students' writing.

"Students are more likely to commit certain grammatical errors because they use the conventions of texting, tweeting and Facebooking in their formal academic essays. Occasionally, I see actual 'text language,' like using the letter 'u' instead of the word 'you,'" Sentell wrote.

Most of the time, it's lack of capitalization, punctuation and apostrophes, Sentell said.

"Everyone speaks and writes differently for different audiences, but some students struggle to switch between the informal codes of texting and social media and the more-formal codes of standard written English and academic or professional writing. After noticing increases in text language and other grammatical errors, I began emphasizing 'code-switching,' or adapting one's writing to one's audience," Sentell wrote.

"I observed a significant reduction in those errors and an increase in the overall quality of my students' writing. But some capitalization, punctuation and apostrophe errors still creep in every now and then."

Central High School principal Mike Cowan, a former English teacher, said texting language has become so commonplace, he even noticed a billboard between Cape Girardeau and Oak Ridge that used "U" instead of "You."

"If we have a disciplinary situation in school, we always invite the student to write a statement about what happened to try and get down to the facts of the situation. They'll write in that kind of informal expression. I see it more all the time. I think it is indeed an academic battle that faculty teachers are fighting ..." Cowan said.

For a while, Cowan said he fought texting, but he's doing it himself now.

"Often I'll get comments that I've been texting in complete sentences. Now I'm going for declarative sentences. I guess I've even relented to some degree," he said.

The bottom line, though, is over time people lose writing skills.

"I guess you could argue it's not a loss, but it's a displacement, a change. I'm not so sure how far you can change and still continue to communicate accurately," Cowan said.

Becky Atwood, coordinator of the Cape public school's Adult Education and Literacy Program, said her students are excellent at texting, because that's their primary written communication.

Older students -- those in their mid- to late 40s -- are "totally lost" on that score, she said.

The two largest age groups served by the Adult Education and Literacy program are 19 to 24 and mid-20s to 40s. Atwood said it doesn't serve "all that many" in the 17- to 18-year-old range.

Atwood said economic and education background affect electronic literacy, as well. "If you were raised ... middle class or above, you're probably technosavvy," she said. "People in some of the lower income brackets, not so much," because they haven't had access to technology.

"It has affected students' ability to write and write coherently. They have to relearn what they might have already known, or learn new skills that they never mastered, because again, they're used to writing informally and now we're asking them to write with a much more formal ... purpose, defending their reasoning, and that's not what they're doing when they're communicating, oftentimes, between friends," Atwood said.

Older students, meanwhile, struggle with the basic computer skills that are needed even at lower-paying jobs.

Also, a lot of the assessment tests students take in high school or adult education programs are computer-based.

"They have to have the ability to keyboard and communicate their thoughts in that manner," Atwood said. "The use of pencil and paper is going away."

Over the next year, Atwood said, her program will launch a transitions course in which adult education and literacy staff will work with students on the next steps to take after earning a high school equivalency diploma.

"Because that or a high school diploma will not be enough to earn a living," she said.

Adult Education has a resource called Missouri Connections, an online program that allows students to access interest surveys, do research on employment, put together resumes and get information on interviewing.

Missouri Connections also has a section on postsecondary education. "We'll help our students use those resources," Atwood said.

If employment is what students want as their next step, she said, the program will help them, and if further education is the goal, support also is available.

rcampbell@semissourian.com

388-3639

Social media studies

An online survey by the Pew Research Center's Internet & American Life Project, in collaboration with the College Board and the National Writing Project in 2012, conducted among 2,462 middle- and high-school teachers showed while half of teachers say digital tools make it easier to teach writing, 18 percent say those tools make it more difficult.

Socialmediatoday.com notes Twitter has made people more concise, as has blogging.

Meanwhile, teachers in the Pew study "expressed concerns about the 'creep' of informal grammar and style into 'formal' writing, as well as students' impatience with the writing process and their difficulty navigating the complex issues of plagiarism, citation and fair use."

* 68 percent of teachers polled by Pew say digital tools make students more likely to take shortcuts and not put effort into their writing.

* 46 percent said these tools make students more likely to "write too fast and be careless."

Pertinent addresses: One University Plaza

301 N. Clark St.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.