Organizations across area striving to cut energy waste

Being green is easier than it used to be. LED and compact fluorescent bulbs use less energy than the incandescent type, reusable and recycled materials can be used in buildings, and energy efficient heating and air-conditioning units are readily available...

Being green is easier than it used to be.

LED and compact fluorescent bulbs use less energy than the incandescent type, reusable and recycled materials can be used in buildings, and energy efficient heating and air-conditioning units are readily available.

With their new construction, Southeast Hospital and Saint Francis Medical Center are taking advantage of all this -- and rebates from Ameren Missouri as well.

Southeast Missouri State University, Southeast Hospital, Saint Francis Medical Center and the city of Jackson are all examples of entities that have discovered the benefits of going greener.

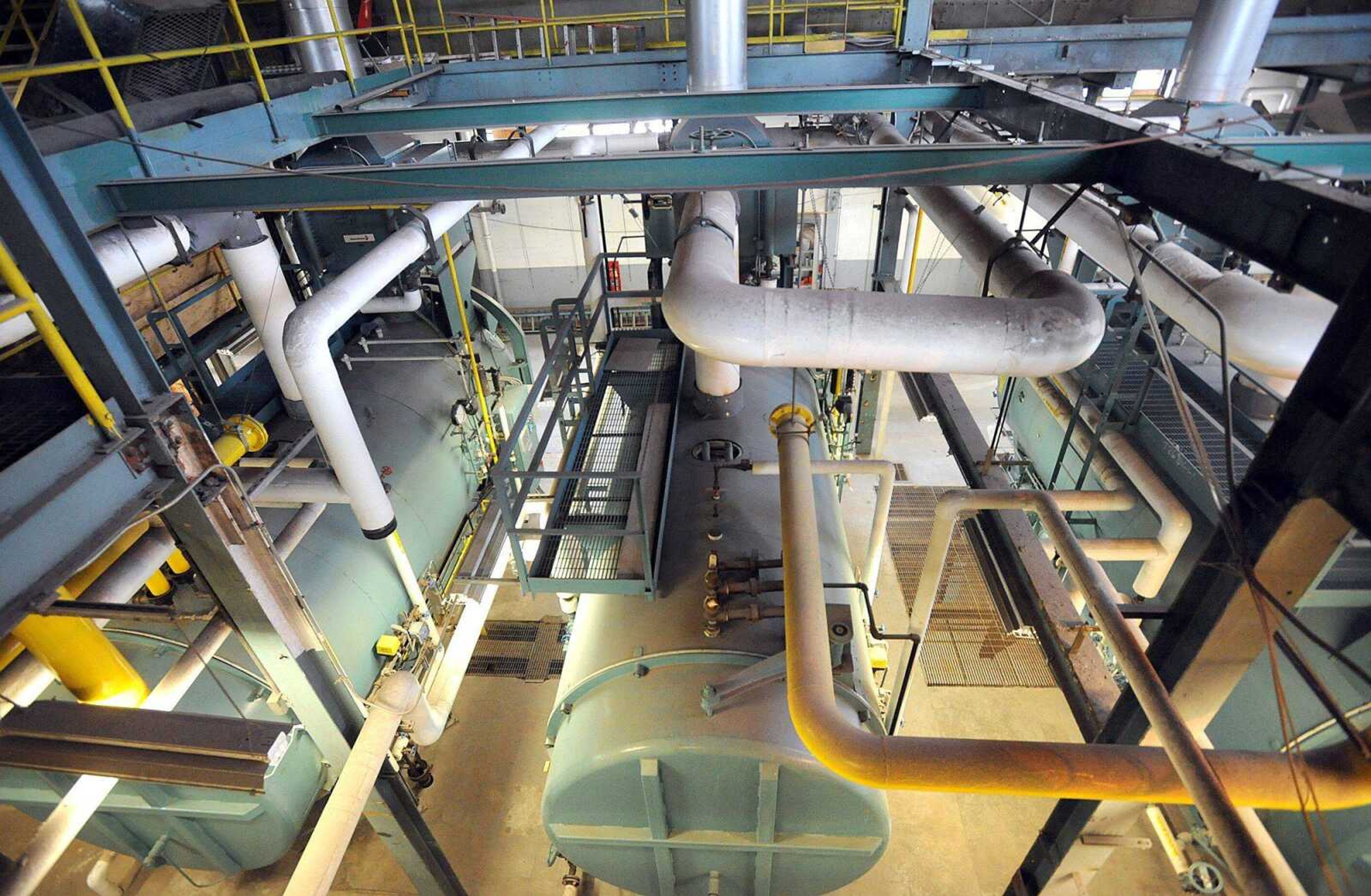

In the past several years, the university has made several environmentally friendly moves, including converting its power plant from coal-fired to natural gas, reducing carbon dioxide emissions from the facility by 65 percent. It also offers car pool tags for students, has put up more bike racks and has planted more trees.

Completed in spring 2012, the power plant conversion has reduced overall university emissions by 25 percent. The project cost $5.8 million, including work on the north chiller plant, said Angela Meyer, director of Facilities Management.

The university's Sustainability Committee, chaired by Chris McGowan, dean of the College of Science, Technology and Agriculture, annually audits the university's carbon emissions, and has been in existence since 2009.

"The goal of the committee is to get CO2 emissions to zero, and we're doing this piecemeal. ... There were economic driving forces, besides the green driving forces, especially in the power plant," McGowan said.

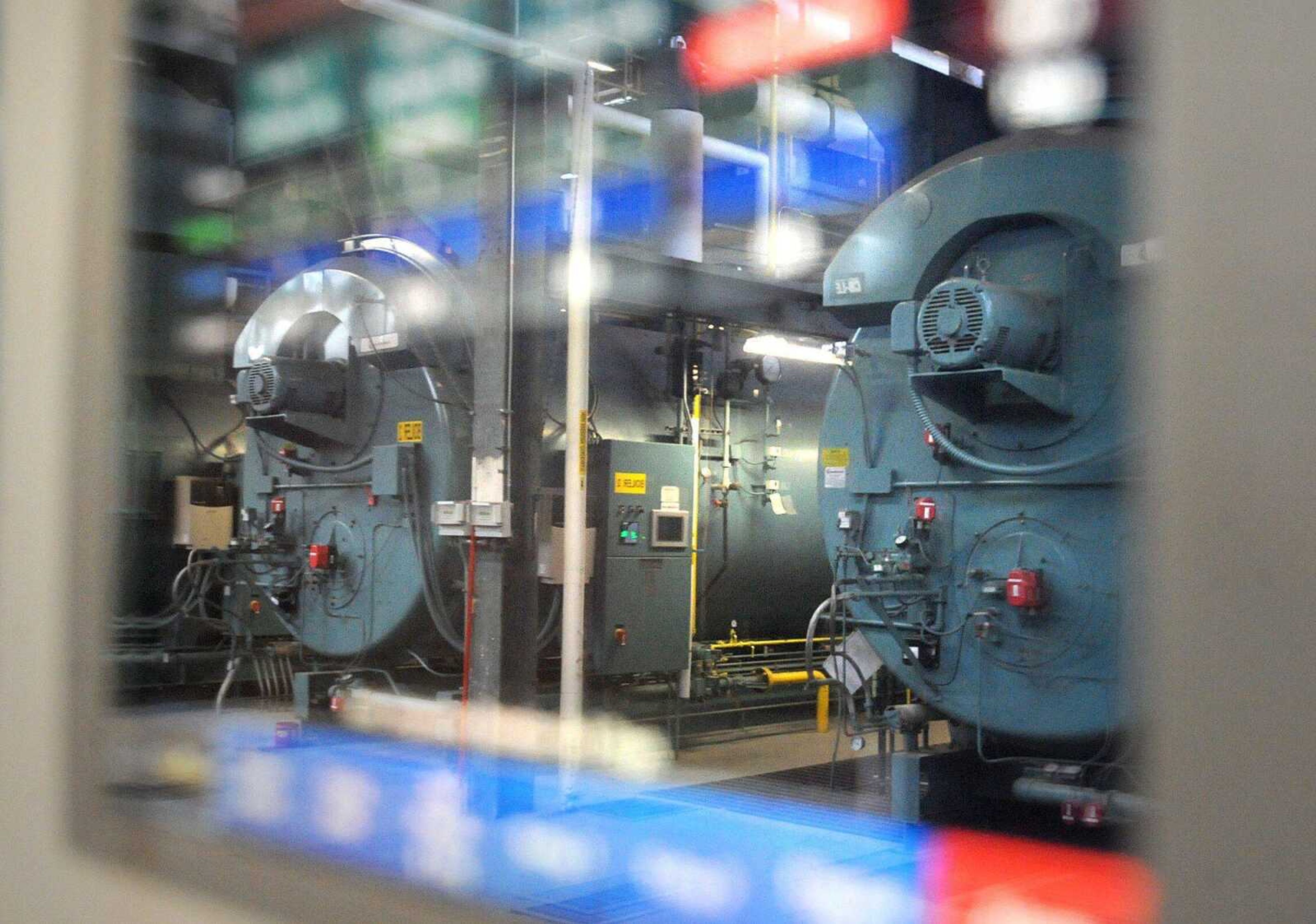

Just off Henderson Avenue on Cheney Drive, the plant still has two coal-powered boilers that boiler plant manager Dustin Cauble says will be torn out. "I think it's cleaner and more efficient [now]," Cauble said.

Additionally, the refurbishment of Academic Hall and Magill Hall, which cost $24.5 million and $22 million, respectively, included features that made them more efficient. On Magill Hall alone, McGowan said, the university could save $1 million a year on utility bills.

"We're saving a lot of money by burning less fossil fuels. We're also producing fewer particulate emissions because natural gas is a very clean-burning [fuel]," McGowan added.

Magill Hall, a science building built in the 1960s, had more ventilation hoods than it was designed to handle. "It was sucking air from outside into the building and then right up the flue from the hoods," McGowan said.

He added the heating and air system was not designed to handle that amount of airflow, so the renovation included redesigning the air handling system.

Academic Hall, built in 1905, had single-pane windows and crumbling infrastructure, so double-pane windows and a more efficient heating and air conditioning system were installed, McGowan said.

Offering hanging parking tags for students who carpool also is a chance to reduce greenhouse gases. Two or three students can get together and buy a placard for less than the cost of two or three individual passes, he said.

In an attempt to reduce the number of cars on campus, more bicycle racks have been set up, and because trees are a natural way to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, the campus is home to more than 2,000 mature trees.

Future carbon reductions will be achieved through large-scale tree planting programs originating at the David M. Barton Agriculture Research Center and the Miller Reserve Wetlands Restoration Project in Scott County. More than 2,500 trees planted during the past year will remove atmospheric CO2 for decades to come, a university news release said.

The university also is looking into replacing lights with LEDs. "There's an investment involved up front, but the energy savings and the payback period is not all that long, so we're investigating that right now as well," McGowan said.

Under its own power

Don Schuette, director of electric utilities for the city of Jackson, said his municipality has been part of the Missouri Public Utilities Association since 2006 to gain some purchasing power. It had been buying power off the grid and through contracts, but looked for an alternative for economic reasons.

MPUA is a not-for-profit service organization representing municipally-owned electric, natural gas, water, wastewater and broadband utilities working together to benefit of their customers, and, in effect, owning the utilities in their community, the group's website says.

"At the time that our contract [was] up, it was becoming so [cost] prohibitive. ... Prices to renew were quite a bit higher," Schuette said.

Jackson uses a mix of coal, landfill gas, solar, wind and natural gas turbines to power the city. Schuette said he didn't think the city was using hydropower at this time. "Our No. 1 concern when we're buying and purchasing power is maintaining the cheapest price for our customers," he said.

The residential price is about 10.5 cents per kilowatt hour. The commercial cost is 11 to 12 cents per kilowatt hour, depending on usage and demand.

Ameren Missouri

Ameren Missouri, which has 1.2 million electric and 127,000 natural gas customers in central and eastern Missouri and whose service area covers 63 counties and more than 500 towns, still uses mostly coal, nuclear and natural gas to generate power, but wind, hydro, solar and methane gas are starting to play a larger role, according to company information.

Fuel prices, generator and transmission system constraints, and the amount of renewable generation and system demand for electricity all factor into the Midcontinent Independent System Operator, a regional transmission organization meant to assure consumers of unbiased regional grid management and open access to the transmission facilities under MISO's supervision.

The energy mix favors coal, since it is the least costly most of the time within MISO, Ameren information says. But these plants are aging and cannot be replaced quickly or easily, the information says.

The company began construction on the O'Fallon Renewable Energy Center in April and is expected to begin delivering electricity to customers by the end of the year.

The plan calls for 19,000 solar panels spanning an area approximately the size of 19 football fields. The solar energy center is the latest milestone in a history of renewable energy investment that reaches back more than 100 years. In 1913, the company's first hydroelectric energy center opened.

In 2012, the company opened the Maryland Heights Renewable Energy Center, one of the largest plants in the nation turning landfill gas into energy, or "methane to megawatts," a news release says. It produces enough energy for nearly 10,000 homes.

New construction

Southeast Hospital and Saint Francis Medical Center are using renewable and recycled materials in their new construction, as well as more efficient lighting.

Several strategies for energy reduction were used in two projects at Southeast Hospital. Brian Gilliland, director of Facilities and Construction at SoutheastHEALTH, said the Nashville, Tennessee, design firm Gresham, Smith and Partners collaborated with the facility's staff to come up with energy savings.

The new extended stay outpatient recovery, Level III neonatal intensive care unit and well baby nursery will open this week. Strategies included using local architectural suppliers and manufactured goods, improved thermal insulation and implementing more bedside patient care support in lieu of distant support spaces.

Engineering strategies included reducing lighting energy by more than 5 percent, independent electrical controls with occupancy sensors and upgrades to existing heating, ventilation and air-conditioning systems for improved air flow and energy performance, according to an email.

At Saint Francis, the hospital is adding 240,000 square feet on the south side of the hospital and about 7,500 on the north side and renovating 140,000 square feet of patient care space in the main building.

"It's an actual guts-and-start-over type of thing. It's a total renovation for those areas to create private rooms where there were semiprivate accommodations," said Rick Essner, director of facilities management for Saint Francis.

The additions are expected to be completed in July 2015 and the renovation in mid-2016, Essner said. Work began Dec. 4, 2012.

The original building was constructed in 1975 and opened around 1976, Essner said.

For the new construction, Essner said it was a conscious move to be as energy efficient as possible. "This has really been a continuation of what we've done in our existing buildings," replacing boilers and chillers with more energy efficient models, he said.

Lighting also has been swapped out and the hospital has taken advantage of Ameren rebates, plus motion sensors have been employed to turn lights off and on as people move in and out of different areas. LED lights feature less wattage, but last longer than incandescent bulbs.

In the new building, Essner said, the hospital is enrolled in the Ameren Energy Efficiency Program and is on track to receive about $300,000 in incentive payments for using energy efficient items.

'It's the norm'

Since the 1990s, and especially the early 2000s, consideration for the environment has become more than a trend, said Jean Ponzi, green resources manager for the EarthWays center of the Missouri Botanical Gardens in St. Louis.

"It's the norm for the building industry," Ponzi said.

The trend gained traction through the 1990s and really took off in the early 2000s because of the influence of the U.S. Green Buildings Council, which has chapters nationwide and internationally.

The organization developed a standard for green buildings that addressed energy efficiency and other benchmarks.

The green building industry also has been a mover in changing how items such as cabinet bodies and vinyl are made so they don't give off pollutants that people shouldn't be around.

rcampbell@semissourian.com

388-3639

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.