Solutions for high gasoline prices might seem painfully far off to drivers as summer travel season begins, but experts say the skyrocketing costs of oil and gas have given new momentum to the push to develop alternative fuels and alternative energy sources.

The efforts are readily apparent in the Midwest, where a boom in ethanol is expanding and scientists are working to turn agricultural waste or "biomass" such as switchgrass, wheat straw, cornstalks and miscanthus into a fuel called cellulosic ethanol that could be produced commercially to reduce U.S. dependence on oil.

In Illinois, biofuels research is underway at Argonne National Laboratory, the University of Illinois, Southern Illinois University, a U.S. Department of Agriculture lab in Peoria and elsewhere, and projects are in the works to revive the coal industry and put up hundreds of wind towers across the state.

The driving force for all the varied efforts: oil. And researchers are thrilled about the impetus that soaring prices have given their work.

"With petroleum prices being as high as they are, the stars are aligning for looking seriously at alternative fuels and chemicals," said Hans Blaschek, a University of Illinois microbiology professor working on the conversion of corn into butanol, a promising alternative to petroleum-based fuels.

Ethanol

Corn-based ethanol might not hold the key to an oil-free future, but it is providing at least a stopgap remedy while scientists look beyond corn for an answer.

The runup in gas prices has softened for now the argument that it isn't economically competitive without federal subsidies, and it has accelerated plans for ethanol plants by farmers' cooperatives and Archer Daniels Midland Co., among others.

Already the No. 2 ethanol-producing state behind Iowa, Illinois is expected to increase its capacity by 50 percent in the next year or two, according to Hans Detweiler, deputy director of energy programs for the Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity, who notes that ethanol-blend gasoline cuts about 8 cents per gallon off the pump price.

All that expanded production will boost ethanol's percentage of the gasoline supply -- currently 3 percent nationwide. Still, its potential is limited by cost and transport issues and the fact that even those seemingly endless fields of corn in the Midwest are finite. Experts say corn-based ethanol isn't ever likely to displace more than 10 percent of the gasoline supply.

"We just don't have enough corn," said Dan Basse, an analyst for Chicago-based AgResource Co.

Biomass

That's where biomass comes in. By using other crops and forest waste along with the entire corn plant, not just the kernels, the Department of Energy says enough cellulosic ethanol could be produced by 2030 to lower U.S. gasoline consumption 30 percent.

Miscanthus, switchgrass, corn stover and other plant waste can be made into ethanol through a process that uses an enzyme to ferment the cellulose, the primary structural component of green plants, into sugar, which is then distilled into ethyl alcohol, or ethanol. Then, just like corn ethanol, it can be blended with gasoline.

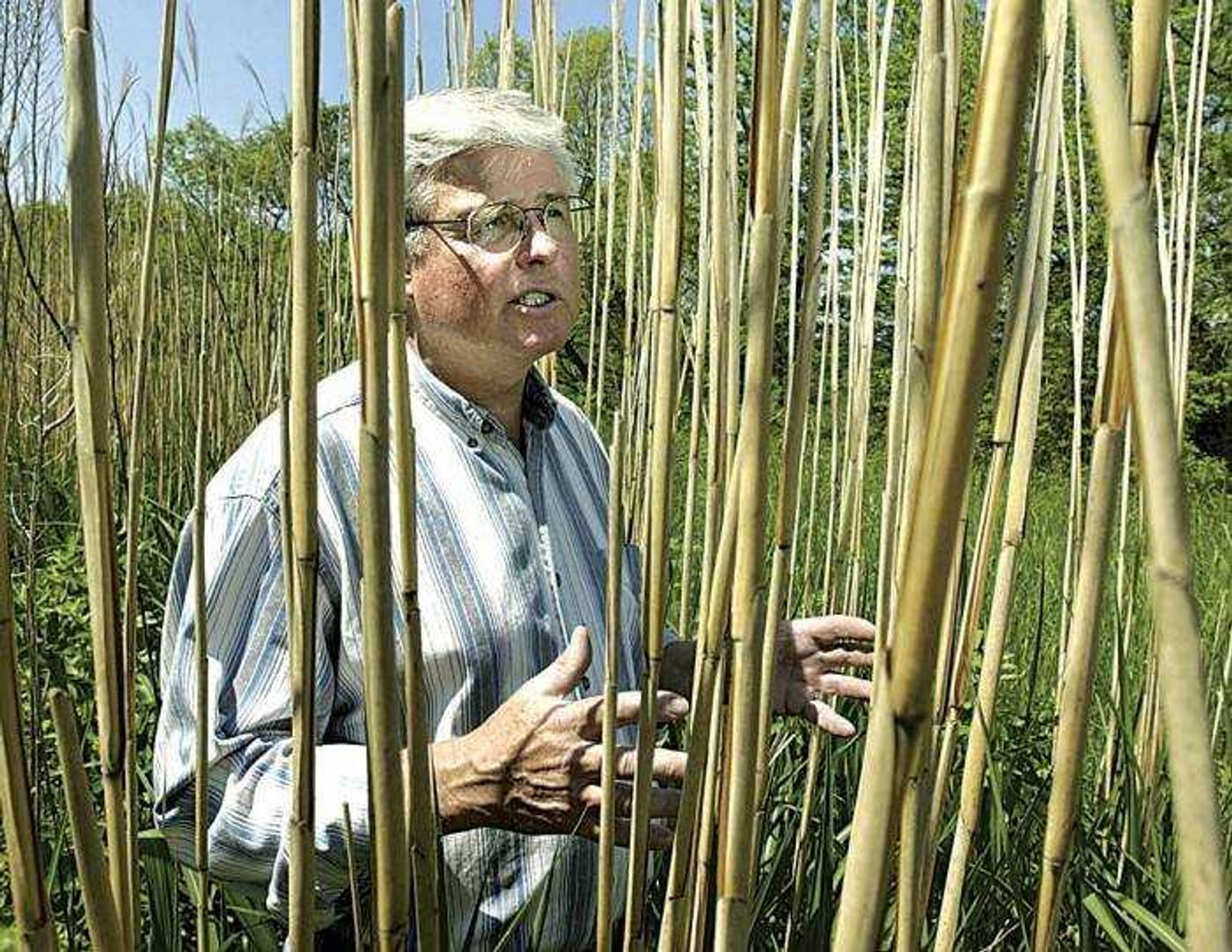

Switchgrass, a prairie grass that can reach heights of seven feet, is being used as a test fuel at a power plant in southern Iowa and has potential as a source for cellulosic ethanol, researchers say. But miscanthus could be an even better source, and a better crop for farmers.

Harvest at test plots across the state indicate that miscanthus could yield 15 to 20 tons per acre, at least double the yield of switchgrass.

"Just as we talk about grain yields and bushels per acre, we're beginning to talk about energy yields in barrels of oil equivalent per acre," said John Caveny, who grows miscanthus on his farm near Monticello, Ill.

Scientists at Argonne, 25 miles southwest of Chicago, and the National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research in Peoria are working on how best to break down the cellulose into sugars.

Mike Cotta, who heads the USDA-run center in Peoria, says many technical challenges remain to be overcome. But a lot has happened in recent years to move them closer to their goal, including great progress cited by Cotta in developing cheaper, more efficient enzymes to break the materials down.

"We're going to need some major breakthroughs, but once these things get in place ... it's going to happen," he said.

Environmentalists and scientists alike applaud the fact that alternative fuels and alternative energy sources are in the spotlight more than ever, but they say energy efficiency is still being neglected.

"There are many people who believe that biomass has the power to replace our appetite for gasoline," said Kimberly Gray, professor of civil and environmental engineering at Northwestern University. "But that will only occur with significant improvements in energy efficiency and smart growth."

Biodiesel

Another biofuel with promise is biodiesel, which uses vegetable oil and other nontoxic ingredients and can be blended with conventional diesel fuel. The trucking industry in particular has interest, and the Department of Agriculture says it can reduce carbon emissions by 78 percent.

But biodiesel is not likely to be an everyday alternative for motorists in the near future. Only a handful of large biodiesel plants exist nationwide.

"It's a small interest, pretty much where ethanol was back in the '80s, but it's growing," Basse said.

Coal

As Illinois' coal industry makes its comeback from darker days a decade ago when clean air regulations made the state's high-sulfur coal unpopular, politicians and energy experts are enthused about the prospects of FutureGen, a prototype for tomorrow's pollution-free electrical generation.

Four Illinois communities are among a dozen from seven states vying for the billion-dollar project, which would turn coal into a hydrogen-rich gas used to produce electricity or fuel pollution-free vehicles.

"FutureGen could be the future of power in the United States," said Rep. Thomas Holbrook, D-Belleville, chairman of the Illinois House Energy and Environment Committee. "We have the largest source of coal in the U.S. The problem with our coal is the high sulfur content, and with scrubbing we think we can take care of that."

Regardless where FutureGen is built, officials are optimistic that Illinois coal has new markets with the spread of cleaner-burning power plants that are better able to burn the state's high-sulfur black ore. Three new mines with a combined 9 million-plus tons of annual production capacity are expected to open this year in the state.

Wind

Illinois has more nuclear power plants (six) than any other state, and that electricity source could someday expand if researchers find a solution to troubling issues of waste disposal and long-term storage. Solar energy, too, might become more than just a niche market if innovations like IIT's solar window can help surmount the same substantial cost challenges that are slowing the commercial development of hydrogen-based projects.

What seems certain, though, is a proliferation of wind farms in a state that until recently had none.

Thanks to the introduction of larger, more efficient turbines, a wind rush is starting to take root on the prairie. Dozens of huge towers now churn the air at two wind farms along a gentle ridge in north-central Illinois and many more such farms are in the planning or development stages.

The U.S. wind energy industry is on pace to install a record 3,000 megawatts this year, according to the American Wind Energy Association, and that's just a precursor to what's coming. In northern Illinois alone, the Chicago-based Environmental Law and Policy Center says, 5,169 megawatts of active wind generation development projects are in planning -- the equivalent of five nuclear power plants or 10 coal plants -- with another 318 megawatts under construction.

"It provides a new income stream for farmers, brings new economic development for rural areas that badly need it and provides environmental quality benefits by avoiding pollution," said Howard Learner, the center's CEO. "At the same time, it's a step toward increasing energy independence."

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.