Local home inspector uses drone technology to zone in on property problem areas

Sam Herndon recently detected a cracked capstone atop a chimney during a home inspection for a potential buyer. That in itself didn't make it a notable discovery. It wasn't his first such find. Rather it was the location of the chimney, situated away from the home's center line -- imagine a smokestack on the side of a mountain -- which it needed to rise above to draw air properly. The pitch was so steep, Herndon, who used to repel and climb, said he'd been reluctant to climb on it with a rope...

Sam Herndon recently detected a cracked capstone atop a chimney during a home inspection for a potential buyer.

That in itself didn't make it a notable discovery. It wasn't his first such find.

Rather it was the location of the chimney, situated away from the home's center line -- imagine a smokestack on the side of a mountain -- which it needed to rise above to draw air properly. The pitch was so steep, Herndon, who used to repel and climb, said he'd been reluctant to climb on it with a rope.

"This unsupported span of this chimney is probably about 30 to 35 feet straight up," Herndon says. "Well, nobody had ever looked at it since the house was first built."

So how did this 60-year-old home inspector get a look to detect the problem?

He sent his Phantom 3 Professional drone to take 4K video and 12-megapixel photos.

"I was able to circle it and check out all the mortar joints, and then checked the capstone on top," Herndon says.

He noted that if a capstone gets cracks, it allows water to penetrate the mortar, causing the joints to weaken.

"Well it had three big cracks in the capstone -- nobody but a drone probably would have found that," Herndon says. "Any other inspector would have looked at it from the ground with binoculars and said, 'OK, it looks OK to me guys. That's all I can tell you.'"

It also might have been his read when he bought the Cape Girardeau-based AmeriSpec Home Inspection Service franchise in November of 2015 and used traditional techniques.

Instead, he was able to inform the potential buyer of the problem.

"I was able to say, 'Hey, you need to get a contractor out here and they're going to have to set up scaffolding and crawl up there. Somebody has to either seal it or replace the capstone on top of that chimney or it's going to disintegrate quickly -- in the next 10 years or so,'" Herndon says. "It allows me to get in places that I couldn't otherwise get in."

In addition to getting Herndon looks at roofs with steep pitches, the drone allows for close examination of roofs constructed with materials such as old asbestos cement shingles, clay tile and wood shingles that can not be walked upon. Other materials are perilous to walk on, such as metal, a surface which Herndon describes as "like walking on a sliding board."

"It allows us to inspect any roof, any place, no matter how high it is, no matter how steep it is, no matter what it's made of, we can inspect that roof," Herndon says about the use of drones.

His conviction of performance is accompanied by appreciation. He climbed all the roofs he could for the first six months of being an inspector.

"I never fell off a roof, but I slid down a roof a couple of times," Herndon says. "Enough to say, 'It doesn't bother me at all to never get another ladder out of a truck.' That's where a home inspector can die is sliding off a roof. We've had inspectors at AmeriSpec that have been hurt real bad falling off of roofs. Plus we're by ourselves. If I fall off a roof at a house, it might be an hour or two before anyone finds me."

Since last May, he's kept his feet firmly planted on the ground, leaving any mishaps to the 2.5-pound drones, which he says he uses 99 percent of the time.

He's damaged two on trees, but he's come a long way since buying one on eBay last April and the first test flight in his own front yard and the ensuing test examinations of his own two-story home.

He later obtained his Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) license and had his drone licensed to meet government regulations, and began on-job use of it when AmeriSpec formulated drone-use guidelines for inspectors in May 2016.

In November, Herndon attended AmeriSpec's national conference, where a company was brought in to teach a seminar on flying drones. He found out he was among a small number of company employees using the technology.

"In North America, there were only three other inspectors there that were using drones on a daily basis," Herndon says.

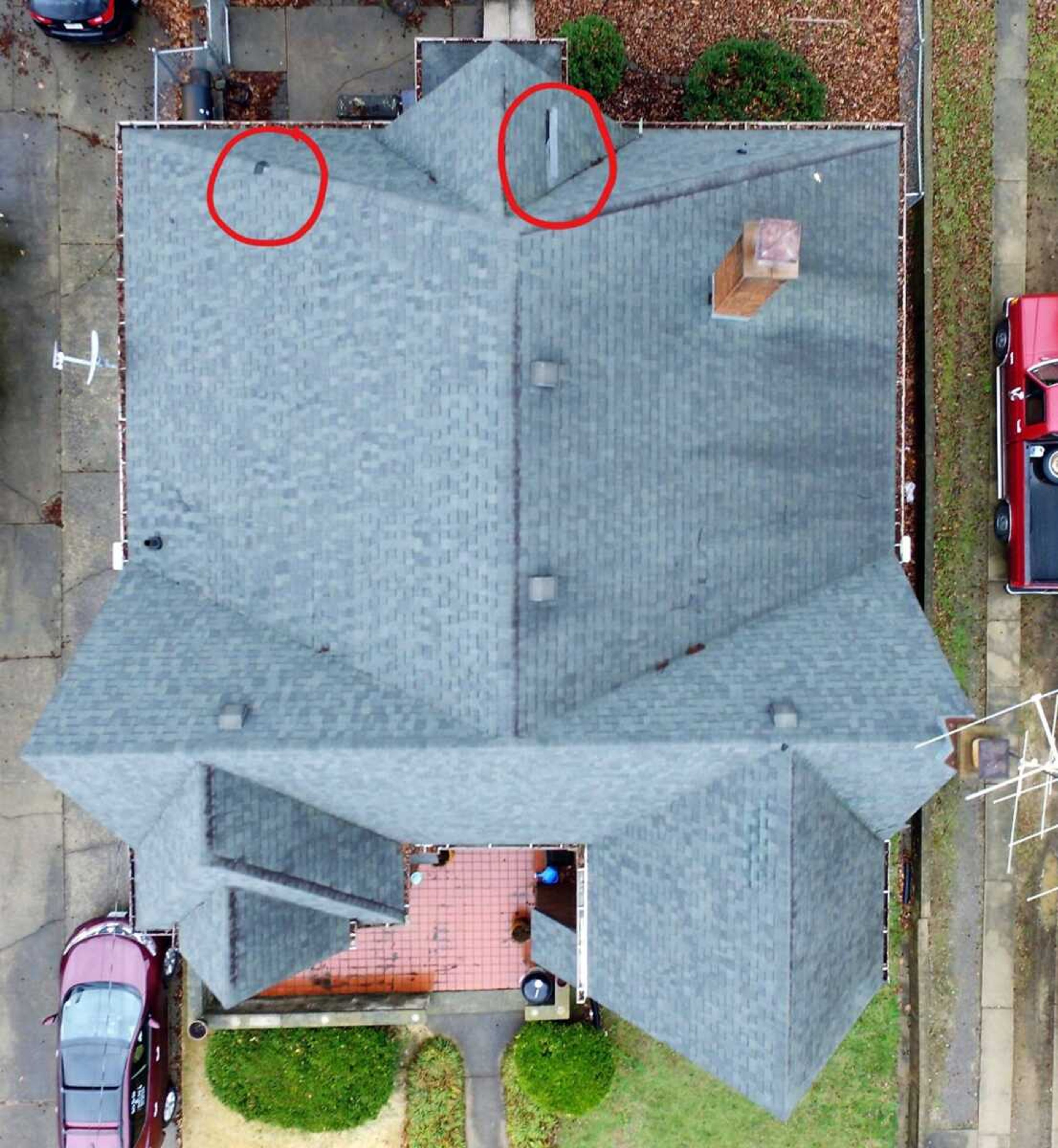

Not only can he get up-close views of roofs, but a distant bird's-eye view provides a perspective that can reveal variations in coloring and potential problem spots.

"It allows me to inspect things that I couldn't see even if I crawled up there," Herndon says.

He's also found the drones to be valuable in examining larger lots, looking for such things as dump sites or buried tanks that are sometimes overlooked on foot. He said one house was located on 38 acres of land, and he was able to video the entire property in flyovers from an altitude of about 100 feet, showing remote fence lines and providing an overall feel for the property to the buyer.

"We looked at the whole piece of property from the air in about five minutes," Herndon says.

The aerial views have sparked Herndon's interest for other hard-to-reach areas of homes, most notably crawl spaces, which contain water pipes, air ducts and the potential for termites and rodents. He said such spaces sometimes can be less than a foot high and inaccessible. Others that do have enough clearance might be too risky to enter due to mold or the potential of venomous spiders or other inhabitants.

He believes radio-controlled crawlers equipped with lights and cameras are the answer to such crawl spaces, which he said are encountered about 2 or 3 percent of the time.

On other fronts, thermal-sensing devices are allowing inspectors to "see" potential problems inside of walls, and improved radon testing equipment is also available, alerting owners and buyers to a potential health hazard.

"We want to be able to tell them everything we can about a house," Herndon says. "And if I can't get into an attic or get into the house, there's a big area I can't tell you anything about that I want to be able to tell you about. So we're always looking for safer, more effective ways to get into every nook and cranny of a house. That's our goal, to be able to deconstruct a house without damaging anything. Take the house apart and tell you what's inside the walls, that's the future direction of this."

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.