Measure what matters. If you're not tracking what drives success, how do you make meaningful change?

This philosophy applies not only to business but also to America's pastime, and in recent years, technology has made it more attainable. From Major League Baseball to college programs -- and even younger in some cases -- coaches and players use analytics to dive deeper into the game.

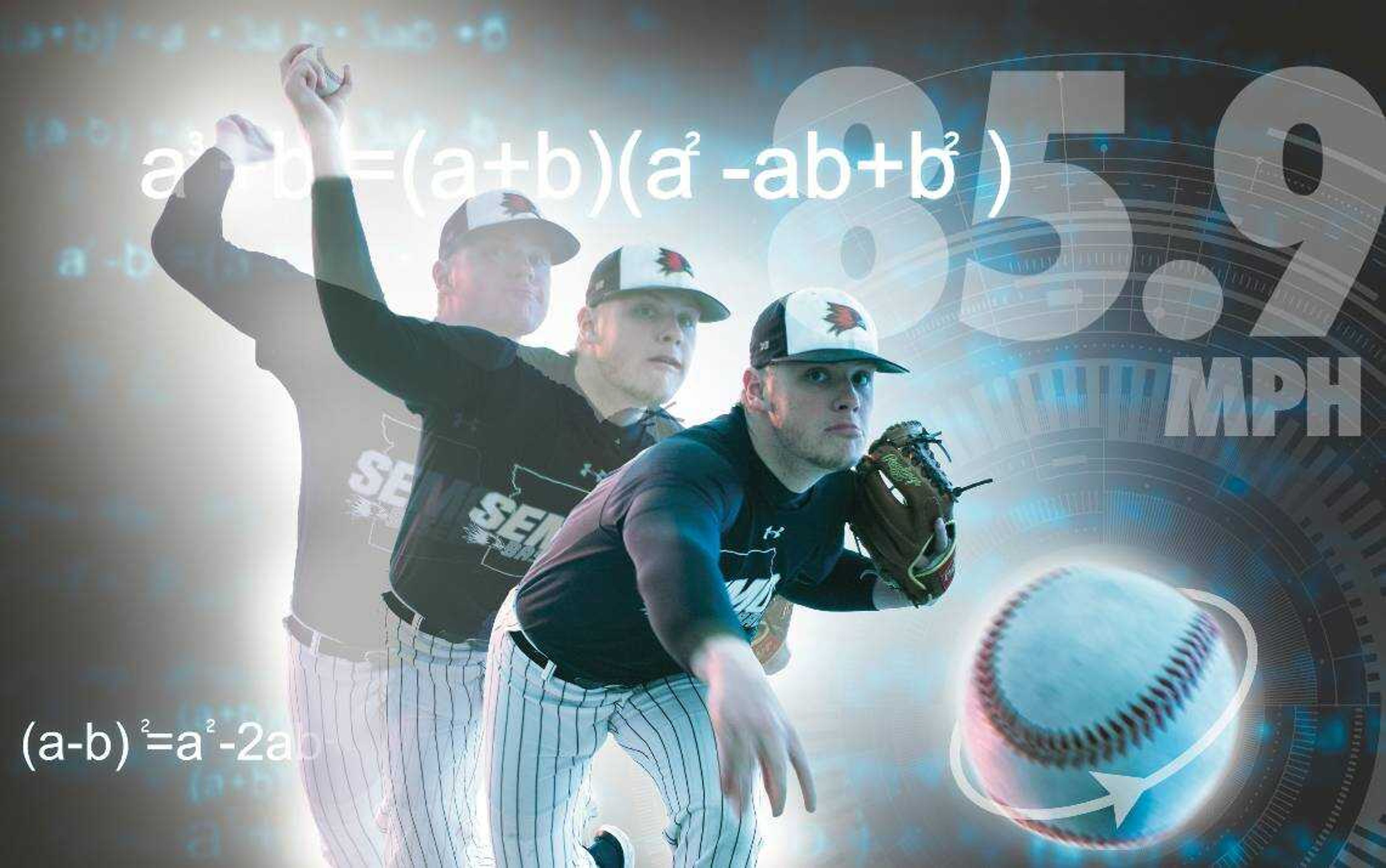

It's not just about wins and losses for a pitcher or batting average for a hitter. Instead, pitchers are looking at spin rate and pitch efficiency, and hitters are tracking exit velocity and launch angle, among other statistics, to understand what they are naturally inclined to succeed in as well as create strategies for development.

On a cold afternoon in February, only days before the Southeast Missouri State baseball team opened its season at the University of Louisiana-Monroe, coaches and players filed into the new indoor practice facility at Capaha Field.

Three batting cages were set up -- two for hitters and a third for Dylan Dodd, the senior left-handed starting pitcher. Dodd was throwing his final bullpen session before opening day using the team's new Rapsodo pitching device setup 15 feet, six inches in front of home plate.

Unlike some younger players who have used similar technology before, this is the first season for Dodd to implement Rapsodo. He said it's helped "tremendously," giving him data to better pinpoint his strengths and weaknesses on the mound.

Redhawks pitching coach Matthew Kinney, seated behind a safety net as Dodd delivered each pitch, gave the catcher instructions on what pitch he wanted to see as he followed analytics displayed on an iPad.

"I just want you to feel your shoulders go down rather than side to side," Kinney said to his pitcher. The reference was toward the pitcher's slider, a relatively new pitch for him, but one that could help change the eye level of opposing hitters.

If Dodd pulled off toward his glove side, the pitch would overdeliver on the horizontal plane. Instead, the coach wanted his pitcher to focus on follow through to maximize the vertical differential while retaining command.

"I try to make sure I'm engaging the lower half," Dodd said after his session, "and making sure every pitch looks exactly the same and the only difference is my grip or just a little movement here in my hand."

For Dodd, the "spin efficiency" stat is important. He said it indicates how a particular pitch looks to an opposing hitter.

"It's really hard for me to feel a difference, but when I can physically look at something and see, 'OK, this is the difference. This is when it was good, and this is when it was bad,' it really kind of helps get consistency of what you're doing right and what you're doing wrong."

Dodd wants to release each pitch in the same spot while having them finish in different locations.

"Video game feel"

Nearby, junior infielder Tyler Wilber finished a round of batting practice using the HitTrax machine. Each batted ball is measured for statistics such as exit velocity -- the speed at which the ball leaves the bat -- and launch angle -- the angle at which the ball leaves the bat. Bigger, stronger players will typically have a higher exit velocity and therefore can pursue greater launch angle to maximize home run potential, whereas a shorter and lighter player will focus on hard-hit ground balls and low-hanging line drives. Fly balls are more likely to be caught.

"I'm trying to get the ball in the air a little bit more," Wilber said. "I'm kind of a little bit of a hybrid. I'm looking to go doubles and alleys and work up from there. So like, I'm trying to hit the ball hard in the gaps, and if it gets up in the air, it might go out for a homer."

Fourth-year Redhawks head coach Andy Sawyers said HitTrax has more of a "video game feel to it." It offers a hard-hit competition and can measure swing quality, which, he said, lends to more players using it.

"It's built that way," he said. "The players like it, so they hit more on it. So for some of those guys who are the tremendous self-starter, it's almost like a game to get them hit more."

Bieser's influence

One coach gaining national attention is Southeast alumnus and former head baseball coach Steve Bieser, who is entering his fourth season as head baseball coach at the University of Missouri.

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported in January that Bieser received a three-year extension that will keep him in the black and gold through the 2024 season.

Bieser's teams at Mizzou have won 104 games during his tenure, the most of any Mizzou baseball coach in his first three seasons. He's humble about the record and is quick to credit the players and coaches. Even so, Bieser -- who previously served as the head baseball coach at Southeast Missouri State from 2013 to 2016 -- is getting results combining baseball intelligence with the latest technology.

Bieser is a data guy, but first he said a coach has to have "great knowledge of the game," understand body mechanics and realize not all players' bodies work the same way.

The analytics are primarily a tool for coaches, he said, but there are some players who really gravitate toward the data.

The Athletic, a subscription-based sports journalism website and app, reported in a Jan. 3 story that three college programs are "on the cutting edge," and even ahead of some Major League programs when it comes to technology. The three: Vanderbilt, Wake Forest and the University of Missouri.

"I want to know as much information as I can get," Braves prospect and Mizzou alum Trey Harris told The Athletic. "I want to be consistent in the right way, I want my ball to take off to all fields."

Harris is one of eight former Missouri players now in professional baseball who used the Mizzou facilities regularly this off-season.

Bieser said he preaches a "growth mindset" to his players.

"We're not immediately going to dismiss something because it's different," he said. "We're going to go ahead and dig into it and see if there's an advantage and we can use it to help us. And I think our players have taken that with them to pro ball."

It's also translated to attracting smart people studying at the state's flagship university to work with the baseball program, mining data and providing insight to the coaches.

"We employ a lot of our students in the stats program and business," Bieser said. "We try to get as many people across the campus who have a lot of interest in the game of baseball, as well."

During Bieser's tenure, five Mizzou students who worked with the team on analytics have moved on to careers in Major League Baseball analytics departments. The university now offers an analytics certificate.

Using data in coaching

St. Louis Cardinals players made their way to Cape Girardeau in January for the annual Cardinal Caravan. When asked about analytics, several hitters talked about not overcomplicating it. The college coaches interviewed for this story agreed. Some players want to know the analytics, others less so. But it's not always about sharing the information directly with players.

"There's certain things I might share with a player, and there's things I would never think about sharing with a player," Bieser told B Magazine. "It can become a mental block for them and get them struggling."

Sawyers referenced the importance of not falling into the paralysis by analysis trap.

"You can get really into the pitching side of things," Sawyers said. "Every pitch, there are like 15 different metrics you can look at if you really want to. The pitcher's not going to look at that while he's throwing, so that lends itself more to the coach taking the data, interpreting it and then using that to help the players improve."

Still, Kinney said for many players, synthesizing data is how they learn.

"The thing is, a lot of our guys, especially the high school guys and the junior college guys, this is how they learn baseball now," Kinney said. "They throw a bullpen and their entire bullpen is rated in Rapsodo. That's great. It doesn't get the whole picture in terms of winning a baseball game, but it's great. So we've got to be able to relate to them with that data with us coaching the way we know how."

Sawyers said the tools can work in a couple of ways. Using pitching as an example, he said the data can help design body manipulation in a way to create specific pitches. But it's also a way to better understand a player's natural abilities and compete from a position of strength.

For hitters, Sawyers referenced the concept of "measurement is motivation."

"We ask everybody to hit the ball as hard as they can on a line," he said. "If you come in and you train and you hit the ball at 88 miles per hour consistently, because you're measuring it, you're probably motivated to improve yourself."

Over time, a player hitting with an exit velocity around 90 miles per hour can begin to see that number increase.

"So in a good round of BP, they're kind of challenging themselves to get more out of their body and be a little bit more aggressive," he said.

Ultimately, baseball is still a game. You're competing. But the data makes some previous subjective discussions more objective.

"Every pitcher would like to throw 95 [miles per hour], and every hitter would like to be a home run hit," Sawyers said. "That's human nature. Rather than it being a negative and the coach saying, 'You can't do this. Like you're not good enough,' [it's] 'Let's see what the data says.'"

As Hall of Famer Yogi Berra once said: "Baseball is 90% mental, and the other half is physical."

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.