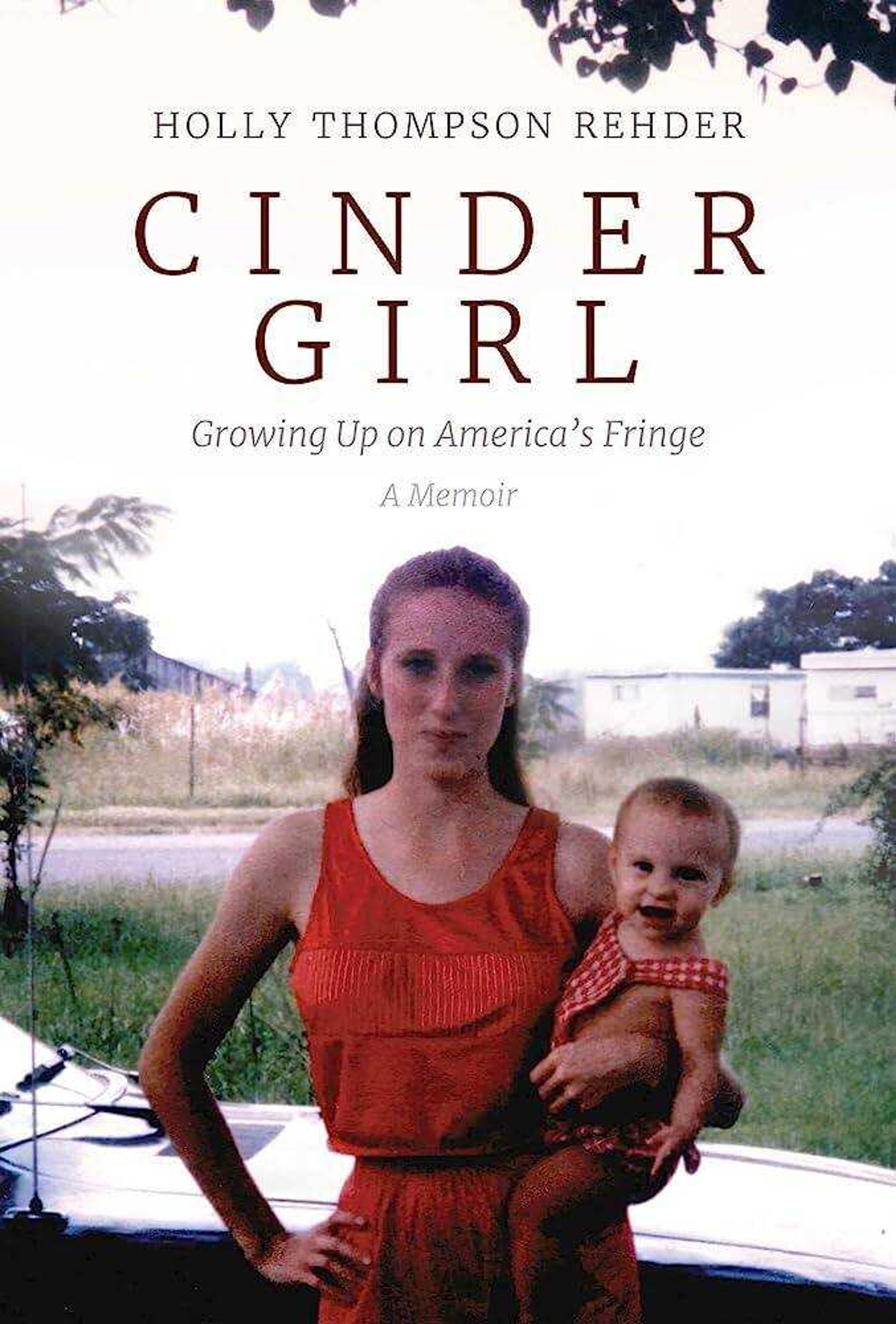

Sen. Holly Thompson Rehder’s memoir: powerful and important to read

Reading “Cinder Girl: Growing Up on America’s Fringe” by Holly Thompson Rehder, who represents a large swath of Southeast Missouri in the Missouri Senate, I couldn’t help but cry, regularly. In this raw, highly intimate and ultimately uplifting memoir, Thompson Rehder tells her story about breaking out of poverty, sexual assault, exploitation and broken homes through Christian faith, hard work and self-discipline. ...

Reading “Cinder Girl: Growing Up on America’s Fringe” by Holly Thompson Rehder, who represents a large swath of Southeast Missouri in the Missouri Senate, I couldn’t help but cry, regularly. In this raw, highly intimate and ultimately uplifting memoir, Thompson Rehder tells her story about breaking out of poverty, sexual assault, exploitation and broken homes through Christian faith, hard work and self-discipline. She does it with a keen eye for detail and scene-setting drama — and a voice full of compassion, even to those who wronged her and others in deep, horrible ways. Throughout, she also serves witness to the ravages of mental health problems, particularly with her mother, and to the miracle of a substance use intervention with her own daughter, who had become addicted to opioids. There are few good men in the book; physical abuse and sexual predation are common occurrences. And police are often powerless — or worse, dismissive.

It’s a book that business and government leaders should read to gain an unvarnished view into a world that surrounds them but is at the same time easily invisible — or ignored, especially by the affluent. For leaders in Southeast Missouri, the book is even more bracing because the towns, institutions and street names are our own, and it puts vivid portraiture to the challenges too many of our neighbors are facing: food insecurity, financial instability, drug addiction, homelessness, mental illness and family breakdown.

Powerful, poignant and written in a conversational vernacular — at times rural and always accessible — it is not a comfortable read.

At one point, a 13-year-old Thompson Rehder, traumatized by the constant beatings and raping of her mother, puts a plan together to kill the man who has drawn her mother in and trapped her.

“To the person who has had a normal life growing up, this seems extreme, I know," writes Thompson Rehder. "But for months I had lain awake to the sounds of my mother slowly dying, being murdered right in front of me and my little sister. Kissing my broken Mama goodnight every evening, her beautiful smile gone, the constant tears in her eyes and the bruises on her neck and arms – sometimes even bite marks – was enough to break anyone’s mind. And it did mine.”

With shotgun in hand, Thompson Rehder was ready to shoot:

“If I didn’t try, he was going to end up killing her. We all knew it. This was our only chance of survival.”

I’ll let you read the book to find out what happens next.

Other parts of the book deal openly with Thompson Rehder’s own sexual assault by a trusted family member, which in part led to marrying at age 15, pregnancy at 16. It was baby Raychel, though, and Thompson Rehder’s foundational Christian faith that gave her focus to break out of the cycle of poverty.

“To me, raising Raychel was the ultimate job and it actually held life-or-death outcomes. I knew the stakes if I screwed this up. She was a live human literally depending on me for everything but breathing.”

There’s a lot of talk about social ills in today’s America, and whether they should be attributed to underlying “systemic” or “structural” causes. Contrasting views emphasize the centrality of personal responsibility and the opportunities in America to “bootstrap” out of poverty. Thompson Rehder’s book provides context to both arguments without getting into politics. It’s a memoir, not a policy analysis. But in her introduction, she touches upon how her experiences shaped her views on government:

“What I have learned, though, from my upbringing, is that our current welfare system too often hinders people’s ability to rise to their potential – like it has for many of the women in my family. As a new state legislator, I quickly realized that those trying to make policies to bring people out of poverty had never seen it from the inside. They have never experienced it, much less gotten themselves out of it. I don’t want to hear the number of people that were cut off of welfare this year; tell me the number of those individuals that are now working full time or have received a degree or training certificate. That’s the number that helps to ensure that generations to come experience upward mobility, and that our tax dollars are not just feeding the cycle.”

She continues later:

“Those of you trapped in the poverty cycle need to see that there is hope, that your upbringing and/or your previous bad choices do not have to define you. Those who have never been in the poverty cycle truly need to understand that many of us are raised very differently. Life has trained us differently. We are jaded. We start from a different lane. Our obstacle course is very different, so, many times, our paths to success simply cannot be the same as those of mainstream America. Government programs that begin by attempting to mash us into that ‘normal’ box do not work well.”

What is clear from Thompson Rehder’s story is that random good deeds — and good people, good education and good government — can make a difference. And support programs, especially those that help feed women and children can be godsends. Having lived in more than 30 houses and trailers by the time she was a teenager, eventually owning her own home changed Thompson Rehder’s situation dramatically, as did being gifted a car — a reward for earning her GED — giving her ability to travel to higher education and work without being dependent on others. The book’s unanalyzed corollary is the perpetuation of poverty through the lack of stable housing and transportation, compounded by landlord exploitation and misaligned public assistance: too much work and pay leads to a greater loss of benefits.

While much of Thompson Rehder’s early life was fraught with harm, her memoir also shares tales of joy and beauty, too, laughter and deep love, even for and from many of those most flawed. Thompson Rehder sprinkles Bible verses throughout as touchpoints of inspiration that give her strength. Without God’s intervention, she is certain she would not have prevailed.

In the end, Thompson Rehder’s book is as much about compassion, hope and forgiveness than anything else. In one of her closing chapters, entitled “Forgiveness,” she writes:

“Why have I been pulled from my pile of ashes – the life I grew up in and the problems I’ve brought on myself? Because one of the greatest gifts God has given me is understanding the importance of forgiveness.

“Jesus taught often about love; love conquers all and the greatest commandment is to love your neighbor as yourself. He said we are to love our enemies and pray for those who persecute us. Easier said than done, I know. I have learned, however, that the key to loving all crazy like Jesus does is forgiveness. And forgiveness is a tricky little thing. On the surface, forgiveness seems like it’s something you do for someone else. Something you are giving them – your forgiveness. But that’s not actually how it works. Forgiveness is something you do for yourself. Proverbs 14:30 says that ‘envy, jealousy, and wrath’ rots the bones. Holding onto that is unforgiveness in a nutshell. And that’s not talking about the person who did you wrong – that’s your bones. When you forgive someone, it is you that gets set free. It is you that finds peace.”

For an inspirational read of hope, triumph and forgiveness, and a stark, oftentimes brutal tour of rural inequities and human failing, which everyone in business and government leadership should grapple with, “Cinder Girl: Growing Up on America’s Fringe” should be on your list.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.