Southeast Missouri Roots & Branches: Getting organized to write your family history

Learn how to organize and write your family history effectively. This guide offers practical tips to preserve your research, overcome writing hurdles and create a compelling narrative.

Most family historians hope to make their research and conclusions available to family or to other researchers. Unfortunately, too many fail to do this. The next several columns will help you start, assemble and write your family history and make it available.

There are good reasons to write a family history other than making it available. It is the best way to preserve your research. Few interested family members appreciate receiving a pile of files, especially if they are unorganized and lack context. Writing is the best way to organize what you have, even if you plan to pass your research along to a younger family member. Oftentimes, there are gaps in your research, and writing up the results is a terrific way to point toward further research to bridge these gaps.

So why do so many family genealogists fail to write a family history? The most common excuse is the fear of being incomplete. However, no family history is ever complete! Even the best researchers miss records, new records become available, insights may occur later, or a family member may fail to bring forth crucial information. You should write about what you have, pointing out gaps that future researchers may fill. Even the best researcher gets side-tracked and goes down a “rabbit hole”. I find myself doing this all the time, but one way to steer back to a writing goal is to decide to allow only an hour or a day to pursue any distraction.

All writers experience writer’s block. If you are “stuck”, then write about another topic or another aspect of the history. Coming back to the “block” later may help overcome it. I often hear good researchers say, “I’m not a good writer”. No one is a perfect writer – that is why we proofread, use spell checkers or grammar checkers, or have others read what we have written and make suggestions. Write it down and revise it later! Finally, all of us know researchers who we perceive as being better than us. This gives rise to “imposter syndrome”. That is, considering we cannot write our family history because we are not the best person to do it. If you get it done, you were the best person to write your family story.

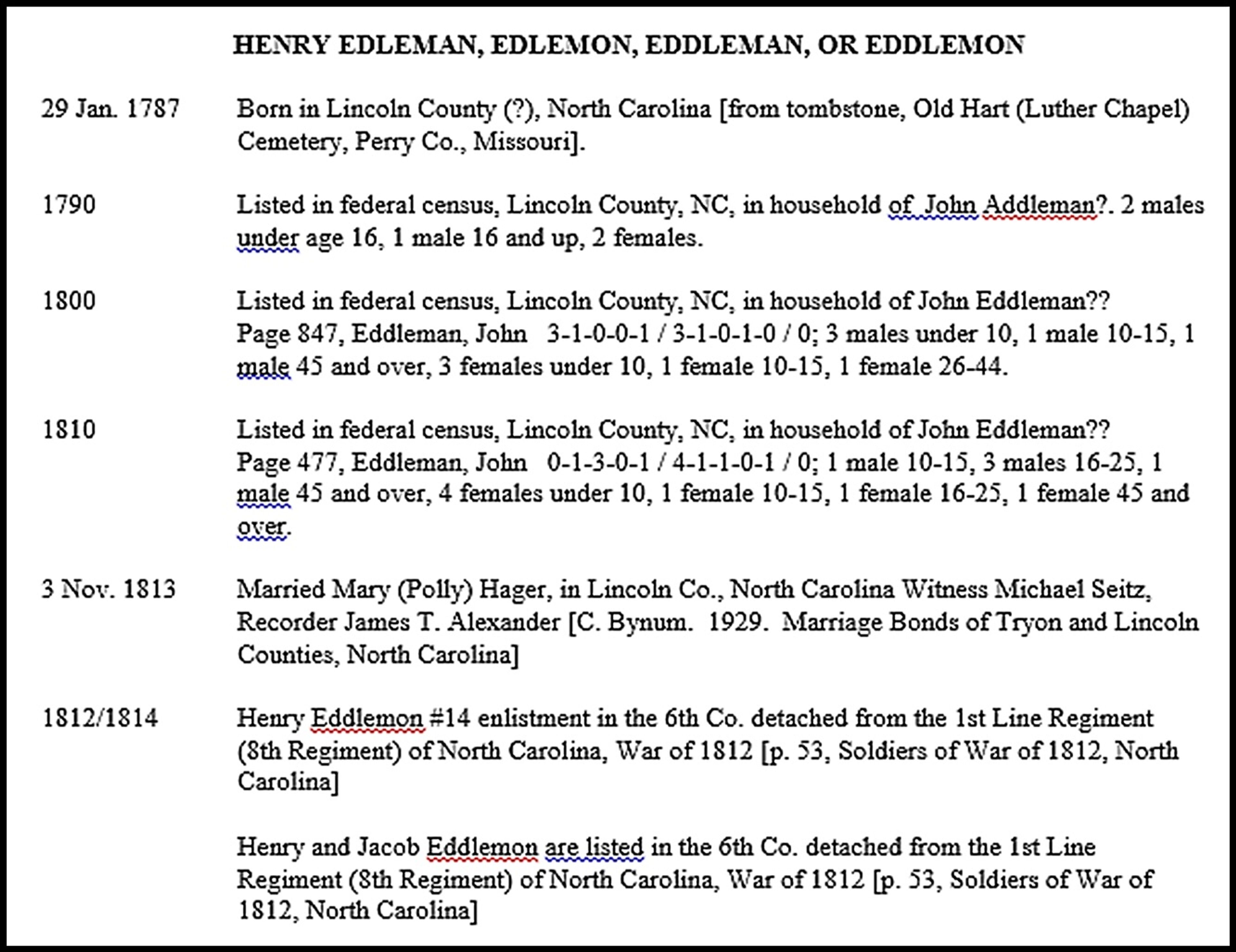

The first step toward writing a family history is to organize your data. In general, this can be by surname, then specific ancestor, and then location if they relocated. A valuable way to do this is to create a timeline of key events in the ancestor’s life. Each event should include citation(s) of sources to support the event. For example, if the ancestor purchased land, you would need a deed book citation (book and page numbers). A good timeline allows you to place the ancestor’s life in chronological order, place events in context and tie your ancestor into events in the larger world. A timeline also leads to an outline of what you want to write about the ancestor and points toward research gaps. If you need practice creating a timeline, start with yourself. Decide on the major events of your life, then find dates and source materials to support the events.

This is also an ideal time to organize files, whether you use paper or electronic files. If you just have a huge pile or piles of paper, organize in binders or file folders, then label and/or color code. Alphabetize by surname, then by couple or family unit. Within files, arrange documents chronologically — for each couple from marriage to death. File children’s information with the parents’ file until the child generates his own records. You can file information about locales, social history and other topics in separate binders or file folders. You should also consider scanning your files. Passing along electronic files is much less daunting than passing along paper files.

If you already store your genealogical research electronically, organize information in directories and sub-directories (equivalent to paper binders and file folders). Use relevant file names, for example, surname — given name — file contents — source (Smith John – Cape Gir Co Deeds 6 - p 340 – 6 Jun 1840). Include scanned photos and document images in the appropriate directory and store in tif or gif format. Images should include attached citation information (equivalent to writing on the back of originals). Back up electronic files often — at least monthly — and store a backup disk in a separate physical location. Strongly consider cloud storage for electronic genealogy files as well and share the password with a trusted relative.

Bill Eddleman, Ph.D. Oklahoma State University, is a native of Cape Girardeau County who has conducted genealogical research for over 25 years.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.