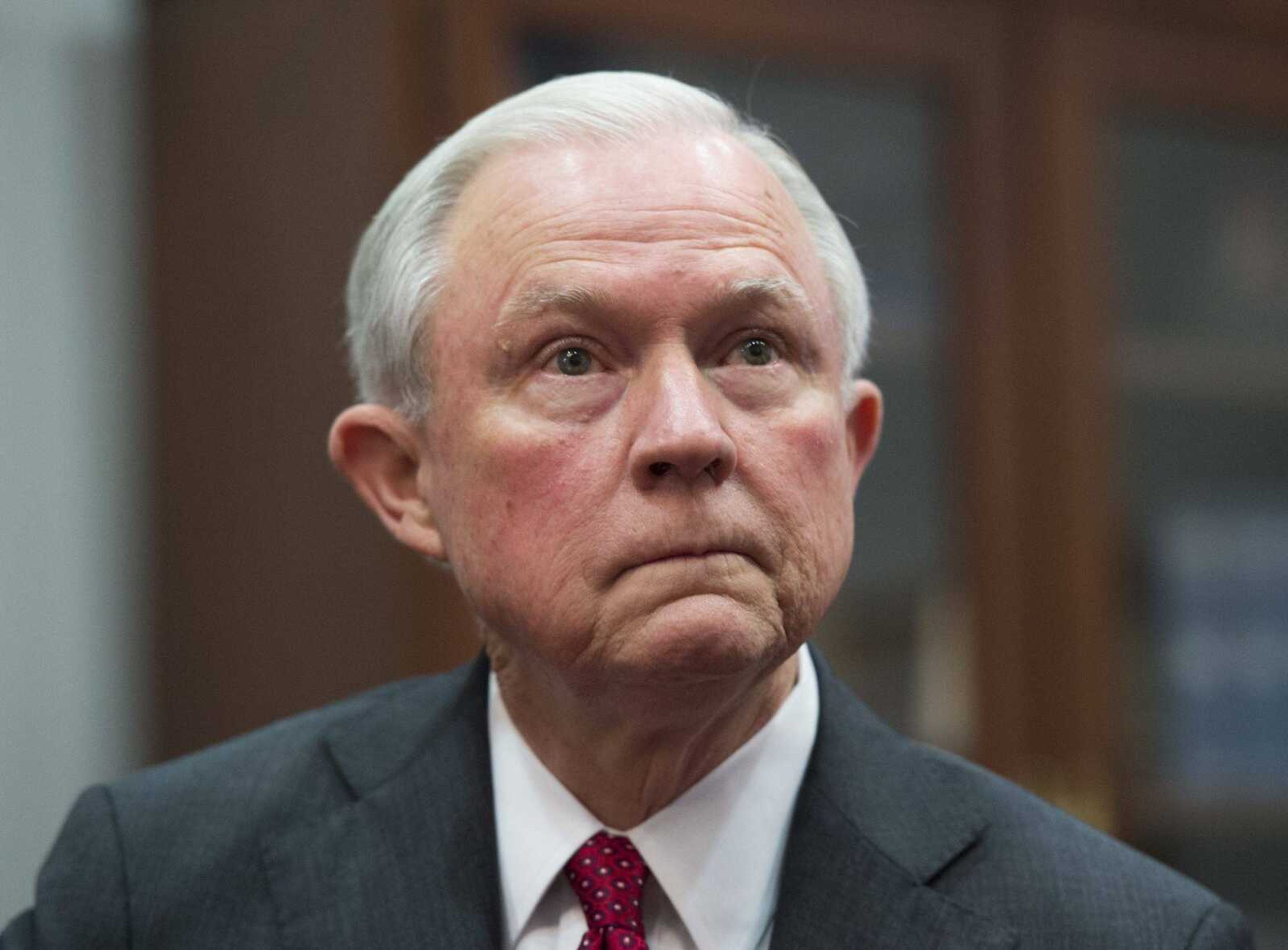

1980s voting-fraud case likely topic at Sessions' hearing

WASHINGTON -- A failed voting-fraud prosecution from more than 30 years ago could re-emerge as a contentious issue during Sen. Jeff Sessions' confirmation hearing for attorney general. Sessions was dogged by his handling of the case as U.S. attorney during his 1986 confirmation hearing for a federal judgeship, when he tried to fend off complaints of a wrongful prosecution...

WASHINGTON -- A failed voting-fraud prosecution from more than 30 years ago could re-emerge as a contentious issue during Sen. Jeff Sessions' confirmation hearing for attorney general.

Sessions was dogged by his handling of the case as U.S. attorney during his 1986 confirmation hearing for a federal judgeship, when he tried to fend off complaints of a wrongful prosecution.

He devoted more space to that case than any in a questionnaire he submitted this month to the Senate Judiciary Committee for the attorney general post, suggesting the matter likely will come up again during his Jan. 10 and 11 confirmation hearing before the panel.

The 1985 prosecution involved three black civil-rights activists, including a former adviser to Martin Luther King Jr., who were accused of illegally tampering with large numbers of absentee ballots in rural Perry County, Alabama.

The defendants argued they were assisting voters who were poor, uneducated and in some cases illiterate, and marked the ballots with the voters' permission.

A jury acquitted the three after just a few hours of deliberation.

Howard Moore Jr., a member of the defense team, said he didn't think it was a legitimate prosecution.

"That's why we defended the case so vigorously," he said. "We felt that it would have had a chilling effect, if they had been convicted, throughout the South."

Sessions has defended the decision to bring the case and suggested in his questionnaire there was ample evidence for a conviction. His supporters note Justice Department officials in Washington approved the investigation and the indictment, and point to one voter's statement to the FBI her ballot had been manipulated and her preferences crossed out and replaced with a different slate of candidates.

The case matters because as attorney general, Sessions would be the federal government's top lawyer in voting-rights disputes, with the authority to challenge -- or support -- state laws dictating access to the polls. He would inherit an agency that under the Obama administration has sued states over potentially discriminatory voting laws but whose enforcement efforts have been stymied by a Supreme Court opinion that gutted a key provision of the Voting Rights Act.

And he could turn the Justice Department's focus to voting fraud, an issue he's sounded the alarm about but current leaders consider virtually non-existent.

"There's nothing in Sen. Session's record that would give me confidence that protecting voting rights from states intent on restricting them is something that would be a priority," said Dale Ho, director of the American Civil Liberties Union Voting Rights Project.

Sessions was U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Alabama from 1981 to 1993, and served two years as state attorney general before being elected to the Senate in 1996.

Ultimately, Sessions' 1986 judicial nomination was derailed by concerns over racially charged comments he was accused of making.

In the upcoming confirmation hearing, he's likely to try to highlight his concern for civil rights to assuage concerns of his Democratic colleagues.

Asked on the questionnaire about the 10 most significant legal cases he's been involved in, Sessions mentioned his office's investigation into the 1981 murder of a 19-year-old black man that resulted in the conviction of two Ku Klux Klan members, as well as litigation that pressed for school integration and for minority representation on a county commission and education board.

He also highlighted his involvement in a separate voting rights case: a 1984 Justice Department consent decree with Conecuh County following allegations that racial epithets were overheard at polling places and that only white poll workers were hired. The agreement required political parties to encourage the nomination of black poll workers and to "ensure that election officials would not engage in racially discriminatory conduct designed to harass or intimidate voters," Sessions wrote.

But the Perry County prosecution remains a focal point.

Sessions, in his questionnaire, wrote that he agreed to investigate the matter after the county district attorney told him that "extremely large numbers" of absentee ballots were being collected and stored in a central headquarters, where they were being altered to ensure they were marked for particular candidates endorsed by the activists. An FBI agent tasked with conducting surveillance outside a post office said he saw the defendants depositing more than 500 absentee ballots to be delivered for counting.

The FBI determined that 75 of 729 absentee ballots contained erasures and alterations, Sessions said, and that about 25 of the voters who were presented with their ballots said they hadn't authorized any changes.

Testifying about the matter at his 1986 hearing, Sessions said "it is horrible to change somebody's vote."

"If I come and pick up your ballot, and you voted for one person, and I walk over and change it and cast it in, that is horrible," he said. "That is not just a petty crime. To do that 25 times is a systematic crime of great magnitude."

The jury wasn't convinced. Nor were Democratic senators. Joe Biden pressed Sessions in the hearing on why a different vote-fraud allegation involving white Alabamians was not prosecuted; Sessions said the evidence was weak. Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts called the Perry County case "infamous," and said that without the help of the three prosecuted activists, "these black citizens would not have been allowed to vote."

Another defense lawyer in the case, Dennis Balske, said prosecutors had little to back up the charges. "We were prepared for 25 people to get up and say, yeah, I voted this way -- and they changed the ballot," he said. "That didn't happen."

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.