Cape center provides safe place for developmentally disabled, respite for parents

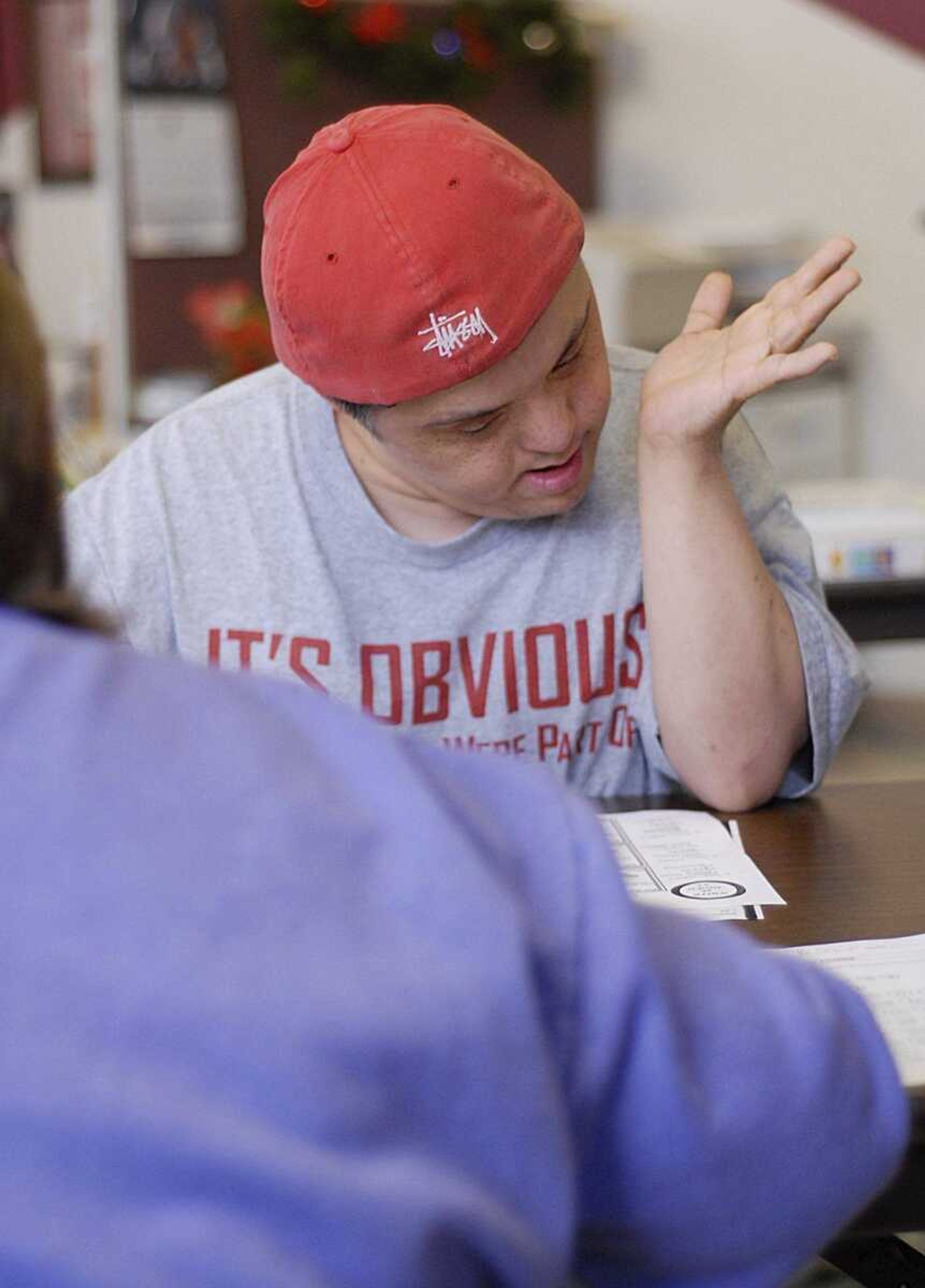

Cara Glueck stands at the front of a classroom quizzing her students about how to add a quarter, a dime, a nickel and a penny. Most know the answer and speak up when called on, although no one is required to. The 10 people in the classroom are all over 21 years old...

Cara Glueck stands at the front of a classroom quizzing her students about how to add a quarter, a dime, a nickel and a penny. Most know the answer and speak up when called on, although no one is required to. The 10 people in the classroom are all over 21 years old.

They learned how to add in special education classes. Glueck, the Horizon Enrichment Center's assistant director and teacher, is trying to assure they hold onto or learn the basic skills they'll need the rest of their lives.

In a different classroom, developmentally disabled adults who can't add or speak spend the day the way most people would like to -- doing pretty much whatever they want. Kim Hindrix, who is in a wheelchair and has cerebral palsy, picks up colored foam alphabet blocks. The support staff has adorned her perpetual smile in lipstick, and she likes it. Eugene Bradley, who is blind and severely mentally disabled, sways to blues music on his headphones.

Located in Notre Dame Regional High School's old building in Cape Girardeau, the center has three purposes: to provide a safe and nurturing environment for those enrolled, a respite for their parents and internships for Southeast Missouri State University students who want to work in the field.

The center can take away some of the stress parents have worrying about whether their children are in a safe environment. But whether they work or have retired, most parents have a bigger concern, director Cindy Schmoll said. "The stress comes from worrying about what's going to happen to their child when they're not able to care for them."

Because of improved health care, the life expectancy of developmentally disabled adults increased from 22 years in 1931 to 59 years in 1976 and 66 years in 1993. By 2030, the number of developmentally disabled adults in the U.S. over the age of 60 is expected to double to 1.2 million.

Some of the same people in the classroom stood on the stage in the gym the night before wearing Santa hats and one by one read lines and held up cards to spell out M-e-r-r-y C-h-r-i-st-m-a-s. Local musician Harry Martin played an electric guitar and led them in singing "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer" and "Jingle Bells." The 60 parents and family members in the audience applauded heartily.

Developmental disabilities are cognitive, emotional or physical impairments that halt or delay progress through the normal stages of childhood. Down syndrome, cerebral palsy and autism are the most common diagnoses of those at the center.

John Votta contracted bacterial meningitis when he was 8 days old. That led to a debilitating stroke.

The graduate of the special education program at Jackson High School needs a stimulating environment and loves being around people. He's a normal young man, said his mother, Mary. "He likes pickup trucks, motorcycles and girls."

Safety for her son was atop her list of priorities when she checked out the center before enrolling him last August. "I'm a 20 questions kind of woman, and I've never stumped them," she said.

John is eager to go to the center each day, she said. "He can only take so much of us. This is school for him."

Carol Hadley said her 36-year-old son, Travis, cries when he doesn't get to go to school. Travis' younger brother Christopher also attends.

'It's a godsend'

The center enables younger parents to work knowing their children are well cared for, said Scott Anderson of Jackson.

"It's a godsend and a blessing."

His 28-year-old son, Adrian, has many hundreds of gospel recordings he listens to at home. He loves going to a thrift store to find more. At the end of last year's Christmas program Adrian instructed everybody onstage to bow. This year his enthusiasm propelled the program along. "He's a free spirit," Anderson said.

One of the attendees arranges all the tables each day when she arrives. The staff at the Horizon Enrichment Center let her. "They allow them to be their own person," Votta said.

Others working at the center include nurse Linda Shirrell, who records all the medications taken, and support staffers Karen Halter and Jackie Carattin. "We're all like surrogate mothers to these guys," Schmoll said.

The center has just begun a relationship with the University Child Enrichment Center just down the block. The purpose is to foster interaction between the children and the developmentally disabled adults. The hope is that when these children grow older they won't experience the discomfort many adults have around people with disabilities.

Adrian Anderson was one of the original handful of attendees whose parents appealed to Southeast Missouri State University in 1998 for help establishing a center that would care for people too old to attend Parkview State School -- 21 is the limit -- and who either were too limited to work for VIP Industries or whose parents wanted a different environment for them.

Some 300 local people with developmental disabilities work six-hour days assembling and packaging products for VIP Industries in Cape Girardeau, Fruitland and Marble Hill.

The center is open from 8:30 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. weekdays. Harry Martin and Kelly Pujol come weekly to provide music therapy at the center. A Main Street Fitness trainer leads an exercise class twice weekly. Some participate in the Mississippi Valley Therapeutic Horsemanship program. Some go bowling.

Reiterating lessons

The higher-functioning individuals at the Horizon Enrichment Center can spend their time learning how to cook or handle money, learning about personal hygiene, learning social skills and exercising or even watching TV. "They are free to do what they want," Schmoll said.

One goal for higher functioning individuals is to reiterate what they learned in high school so it is retained.

After the Christmas program, everyone goes to one of the classrooms for sandwiches and desserts. Santa Claus walked through the door, causing an excited buzz.

Glueck said she learns more from her students than they do from her. "They're open with their emotions," she said. "They're more honest than anyone I've ever worked with."

sblackwell@semissourian.com

335-6611, extension 137

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.