Improved Cache flow

ANNA, Ill. -- The internationally recognized Cache River swamps and marshes sit at the junction of four dramatically different geological areas. Efforts to protect the wetlands from manmade damage bring together some equally divergent groups of humans...

ANNA, Ill. -- The internationally recognized Cache River swamps and marshes sit at the junction of four dramatically different geological areas. Efforts to protect the wetlands from manmade damage bring together some equally divergent groups of humans.

Environmentalists, scientists, farmers and public officials work together for a purpose recognized by the best award governments can bestow -- significant funding for projects developed as a cooperation between public and private interests.

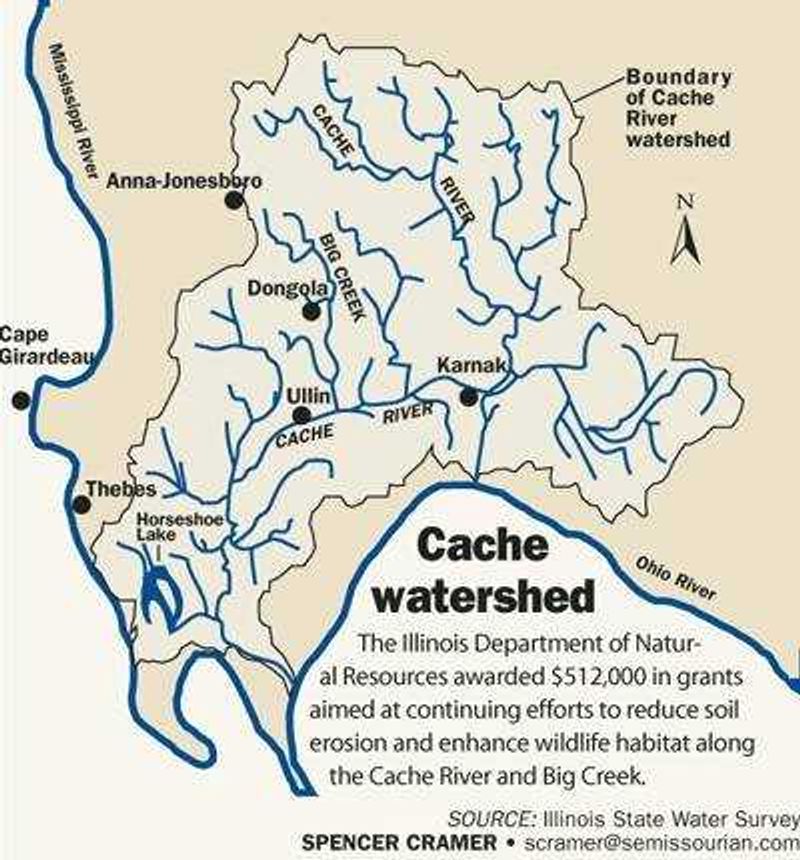

In November, the Illinois Department of Natural Resources awarded $512,000 in grants to the Union County Soil and Water Conservation District to fund three grant proposals. The grants -- 12 percent of the Conservation 2000 program funds awarded statewide this year -- are aimed at continuing efforts to reduce soil erosion and enhance wildlife habitat along the Cache River and Big Creek, a major tributary.

The money comes on the heels of $1 million the district has been using to construct water retention structures along the 51.7-square mile Big Creek watershed to slow down floodwaters and reduce erosion that clogs the wetlands.

The $1 million grant came when the Big Creek project was one of four pilot projects in Illinois designated to show best practices for erosion control and habitat enhancement. The Big Creek project is the only one that has survived to completion. Two never got out of the planning stages.

"It is a pretty massive task," said Randy Holbrook of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources. "It needs the right people and the right groups to spearhead it. And they have the right people who can handle a big project."

Cache River, its tributaries and surrounding landscape are dramatically different today than they were 100 years ago, district conservationist Keith Livesay said. Swamps have been drained, forests cut down and creeks straightened by landowners and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The changes, especially the loss of trees and the straightened creeks, dramatically increased erosion. A study conducted in 2001 by Misganaw Demissie for the Illinois State Water Survey found that 70 percent of the sediment reaching the lower Cache River was coming from Big Creek. Big Creek's Watershed covers only 14.4 percent of the 358-square-mile area drained by the lower Cache.

Demissie's study proposed dozens of alternatives for controlling runoff and sediment. Livesay, in conjunction with his district board and with help from the state, chose a proposal to control 5 percent of the runoff through a series of small water impoundments.

Rock structures along creek banks and creek beds slow down the water, allowing sediment to settle as it moves downstream.

There are very few restrictions on what landowners can do with the water stored, Livesay said. They can stock fish or just leave it alone. "They can irrigate with it, put a beach on it and have a swimming hole or they can use it for livestock watering," he said.

The district pays 75 percent of the cost with grant money. The remainder comes from the landowners, who can provide their share by doing work on the construction rather than paying cash.

While the $1 million pilot project funding was targeted to Big Creek, subsequent grants are based on competitive proposals. Union County's ideas fit well with the Conservation 2000 goals and score well, Holbrook said.

"They had the benefit of a lot of research, and they wrote good projects," he said.

When a big rain comes, the water filling the retention pools releases slowly through a 10-inch pipe. That helps simulate the release of water as it would flow if the land was still forested.

Soil and water conservation districts were first established following the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. Young engineers, fresh out of college with bright ideas, were sent to the countryside to figure out how to control erosion.

But they weren't well received, Livesay said. "They said, You need to do this, you need to do that. The farmers kind of rebelled."

Boards run by landowners helped. There's no rebellion today in the Cache River watershed over conservation proposals.

At the lower end of the Cache River are the Cypress Creek National Wildlife Refuge and the Cache River State Natural Area. The 35,000 acres, purchased with help from the Nature Conservancy, are listed among the world's most important wetlands under an international treaty signed in 1971 in Ramsar, Iran. The Cache River is a rare location because it drains one of the few areas in Illinois not covered with glaciers during the last Ice Age. The Shawnee Hills, the Ozark Plateau, the Mississippi Delta and the Central U.S. Plains meet along the Cache drainage area.

Other U.S. areas listed with the Ramsar organization along with the Cache River include the Everglades and the Okeefenokee Swamp.

Sediment is a major problem in preserving the marshes and swamps along the Cache, said Michael Baltz, Southern Illinois project director for the Nature Conservancy.

"There was a lot of sediment coming into the system that wasn't being flushed out," he said. "The headwaters were not coming in and unclogging the arteries."

The marshes are home to an average of 200,000 Canada geese every winter as well as more than 60,000 other waterfowl. Numerous endangered or threatened species make their home in the refuges.

Landowners along Big Creek consider themselves as dedicated to protecting the land as anyone, said Carlyn Light, chairman of the conservation district board. Light can trace his roots in the area back to the beginnings of European settlement.

"The key to these projects is the landowner," Light said. "Everybody is working together on this."

A typical water retention project will hold back runoff from a 50-to-100-acre area. And creek stabilization structures mean that the water that does drain goes more slowly.

Porterfield Creek, which runs near Light's home, had cut itself more than 10 feet into the earth during his memory. A small bridge over the creek has washed out numerous times, and in the past the water ran a chocolate brown with silt.

In the mid-November storms that dumped 8 to 10 inches of rain across much of the region, the small creek rose but did not flood the bridge. And while it showed it was carrying sediment, its color was more natural, Light said.

The investments in erosion control, which also include programs such as the Conservation Reserve Program of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, have made a big difference for wildlife, Light said.

What makes farmers enthusiastic, Light said, is that the programs aren't directives or orders. The district forms its ideas with input from landowners and applies the research to their needs, he said.

"Farmers don't get the credit they deserve for being the conservationists they are," he said. "They are proud of their land. They don't survive letting their farms go into ditches."

The importance of proving that a 5 percent reduction in peak flows along Big Creek can provide major benefits is it's an affordable goal, said Laura Keefer of the Illinois State Water Survey.

"Most of your sediment is eroded in very little time of the year, by large storm events and large flood events," she said. "If you reduce how high the peak is, you remove a lot of the energy out of that water to erode."

At one bend in Big Creek, for example, Livesay points out where a small amount of rocks placed strategically along the bank will stop a serious erosion problem. The water was hitting the bottom of the bend, cutting under the soil and causing large amounts of dirt to slough off into the current.

To use conventional methods, protecting the bottom 3 feet of the bank along the entire length of the bend would have cost $100,000, Livesay said. The rock in place, which was designed to hold a strategic point, cost $9,000.

"It will do its job for 30 years," he said.

rkeller@semissourian.com

335-6611, extension 126

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.