A 42-year-old woman returned from a weekend getaway in 1998 and, without provocation, stabbed her mother more than 40 times with a 10-inch knife before continuing her rampage on unsuspecting neighbors.

Two years later a Jackson teenager perched himself at the top of a stairway -- like a hunter in a tree stand, he would later tell police -- and shot his grandmother in the head, ending her life as she watched television.

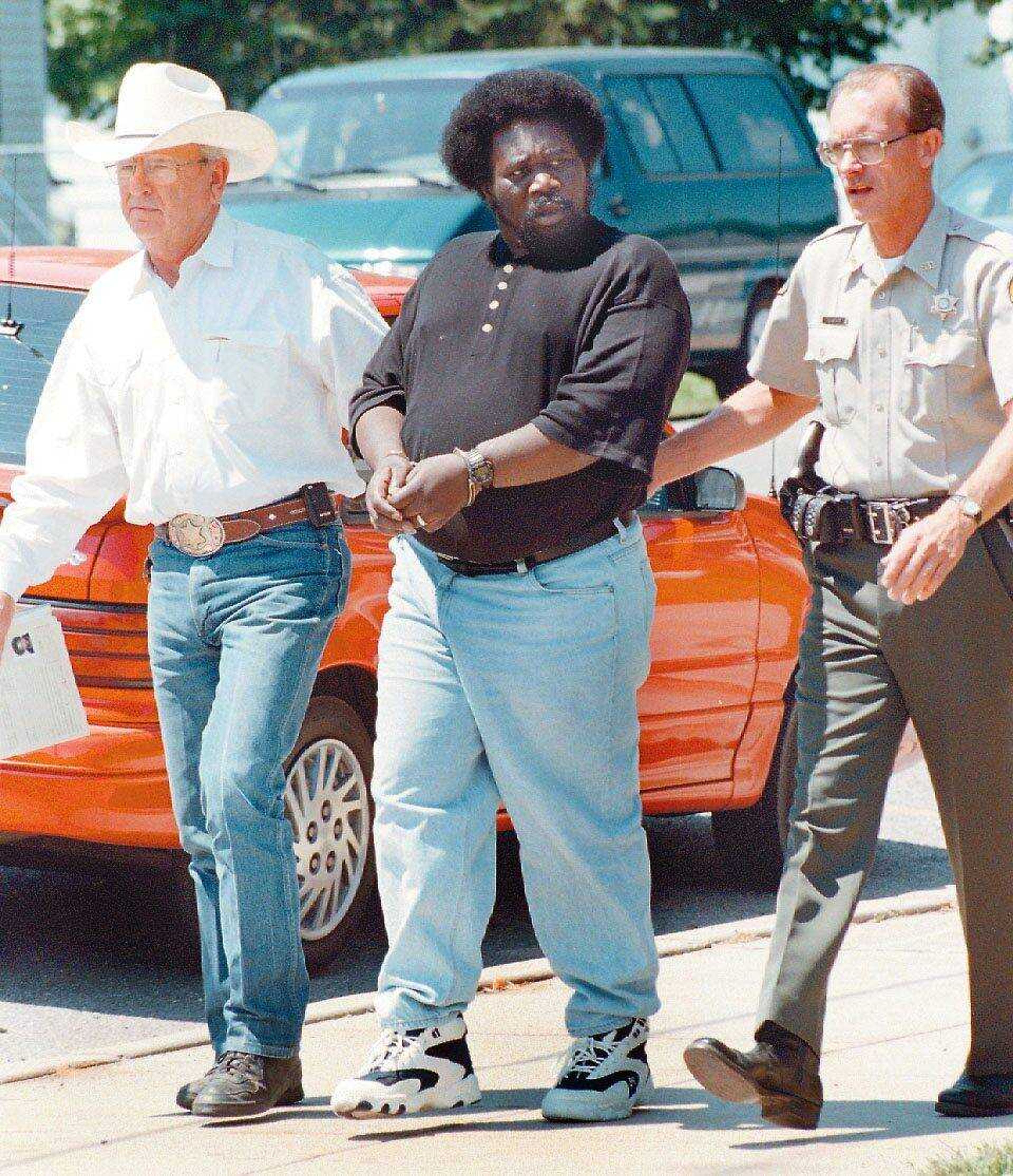

And, almost exactly 20 years ago, an imposing figure interrupted a quiet Sunday morning with three blasts from his pump-action shotgun, one for each of his targets: a former ex-girlfriend, her mother and the man's 11-month-old son.

These gruesome events all took place in Cape Girardeau County during the past 20 years. Though not unheard of, crimes of such fury are rare in Southeast Missouri and seldom garner media exposure elsewhere. But the accused here -- Roberta Burrell, Joshua Wolf and Andrew Lyons -- as well as several other local examples, have one thing in common with nationally notorious names such as John Hinckley Jr., David Berkowitz and Jeffrey Dahmer.

The insanity defense.

Burrell had been diagnosed with schizophrenia when she was a child. Wolf was said to be bipolar and to suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder. Lyons claimed to hear the voice of Jesus Christ and other auditory hallucinations as well as suffer from serious depression.

Now add Lawrence Guthrie of Jackson to the list. Guthrie's lawyer filed a motion earlier this month that claims his client's PTSD is what caused him to open fire in June on a handful of police officers and his estranged spouse. Before the shooting stopped, Guthrie, a military veteran, had turned the gun on himself.

Guthrie, 46, now with a chin brace, will be back in a courtroom Friday to ask a judge to reduce his $500,000 bond.

While his actions weren't deadly like the others, Guthrie and the other aforementioned former defendants are among the few in Cape Girardeau County and across the U.S. who attempt an insanity defense that asserts that their mental illness is so severe they didn't know what they were doing.

The insanity defense has been around for more than 100 years and since then has been one of the most hotly debated topics in criminal law. It is a discussion marked by stereotypes and misperceptions, skepticism and even denial. Some say most are fakers trying to avoid incarceration. Others say those who suffer from severe mental illness deserve compassion and treatment.

While public perception is otherwise, an insanity plea is as rare as the crime. A survey revealed that a majority of respondents believe it is used about 40 percent of the time, perhaps because the insanity plea is so often depicted in film and books. But one study shows that it is used in only about 1 percent of all felony charges.

Some also see it as a get-out-of-jail free card that works most of the time. That's not true either. It is successful much less often than it is tried -- about a fourth of that original 1 percent are found not guilty for that reason.

It is a system that is often misunderstood by a tough-on-crime populace, said Ann Dirks Linhorst, an assistant professor of criminal justice at Southern Illinois University-Edwardsville. Linhorst recently co-authored an article about the topic that analyzed nearly three decades of insanity cases in Missouri.

That's because putting the two systems, criminal justice and mental health, into the same conversation elicits various reactions from an often misinformed public, she said.

"The criminal justice system is complicated anyway," Linhorst said. "But when you then introduce aspects of mental health needs or potential needs, it becomes even more complicated."

Linhorst is in a special position to know. For 15 years before she entered the academic world, she was the forensic director of the Missouri Department of Mental Health. That means she basically ran the program that dealt with those who had pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity. Linhorst's research confirmed what she already suspected: that the public thinks a majority of those who use the insanity defense are guilty defendants trying to beat the system.

"Mental illness is not well understood," Linhorst said. "And most people have a belief, like we all do, that people who commit crimes need to be held responsible."

In Missouri, the statutes present two opportunities for someone charged with a crime to claim mental illness -- before a trial and during one, said Cape Girardeau County Prosecuting Attorney Morley Swingle. The U.S. Constitution prohibits anyone with a lack of mental capacity to be tried, convicted or sentenced, he said. A defendant, after all, has to be able to assist in his own defense, Swingle said.

The statute goes on to say when a judge has reason to believe that the accused lacks mental fitness to proceed, he can -- either on his own motion or one from the prosecution or defense -- appoint a state psychiatrist to perform one or more evaluations before trial. If the defendant is found to be mentally unfit, the judge can commit the defendant indefinitely to one of Missouri's four state psychiatric hospitals.

Lawyers for Andrew Lyons and Roberta Burrell, for example, each had psychiatric evaluations before laying eyes on a jury, though only one of them would avoid a trial altogether. In the week following the triple murder, Lyons attempted suicide in his cell by trying to electrocute himself while being held at the Cape Girardeau County Jail. He tried using telephone wires and then breaking through a metal casting around a light bulb in an effort to shock himself while standing in a puddle of water.

Judge Benjamin Lewis ordered Lyons, then 35, to undergo a mental evaluation at Fulton State Hospital. Lewis said at the time that Lyons was "a danger to himself," one of the requirements. After the 96-hour hold, Lyons was returned to jail.

Another judge, William Syler, said later at Lyons' arraignment that he wanted another mental evaluation to make sure Lyons was fit to proceed to trial. The state psychiatrists said that he wasn't. Lyons was found incompetent to stand trial for the three counts of first-degree murder after doctors said he wouldn't be a "willing participant" in his defense because of deep depression.

For more than a year, Lyons was a patient Fulton State Hospital. When he first arrived, he told psychiatrists he could hear "the voice of Jesus Christ and his son." Lyons was still suicidal when he arrived in Fulton. But he was taken off suicide watch the same month he got there and got a job in the laundry, where he was commended for his job performance.

For his good work, a judge eventually ruled, based on the recommendation of the Missouri Department of Mental Health, that Lyons was fit to stand trial for murder.

"The state said that they felt like he was ready to assist in his trial," Swingle recalled. "And the judge agreed."

The other case that was interrupted by the insanity plea before trial was the one of the woman who stabbed her own mother more than 40 times. This is one case of mental illness that Swingle didn't object to when it was broached by the defense attorney before trial.

In October 1998, police arrested Burrell for the murder. Diagnosed with schizophrenia as a child, Burrell was fine as long as she did not neglect to take her medicine. But Burrell had been away at a weekend religious retreat where she was told God would eliminate her need for the medicine and she should stop taking it.

She did.

On Sunday, when she got back, Burrell went to her mother's apartment on Linden Street and found her ironing. That's when she proceeded to stab her mother more than 40 times, including one final slit of her throat. After stabbing her mother, the knife-wielding Burrell terrorized the neighbors of the apartment building, breaking into apartments and making threats.

After she was arrested, Burrell was put back on her medicine. Swingle said when Burrell returned to her senses, she was horrified to learn what she had done to her mother. Burrell was taken to one of the state psychiatric hospitals without objection from Swingle.

Swingle said he couldn't help but feel sorry for the woman, unlike a murderer who commits the crime for greed or revenge.

"The criminal chooses to murder their grandmother because they want the inheritance money or they didn't like the person," Swingle said. "But the person who truly has an illness and didn't know what they were doing when they did it and then is horrified they did it? You really do feel sorry. It's a tragedy for everybody."

Coming Monday: Cunning killers or mentally ill? The trials of Andrew Lyons and Joshua Wolf.

smoyers@semissourian.com

388-3642

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.