Maritime traffic jam grows outside blocked Suez Canal

SUEZ, Egypt -- A maritime traffic jam grew to more than 200 vessels Friday outside the Suez Canal and some vessels began changing course as dredgers worked frantically to free a giant container ship that is stuck sideways in the waterway and disrupting global shipping...

SUEZ, Egypt -- A maritime traffic jam grew to more than 200 vessels Friday outside the Suez Canal and some vessels began changing course as dredgers worked frantically to free a giant container ship that is stuck sideways in the waterway and disrupting global shipping.

One salvage expert said freeing the cargo ship, the Ever Given, could take up to a week in the best-case scenario and warned of possible structural problems on the vessel as it remains wedged.

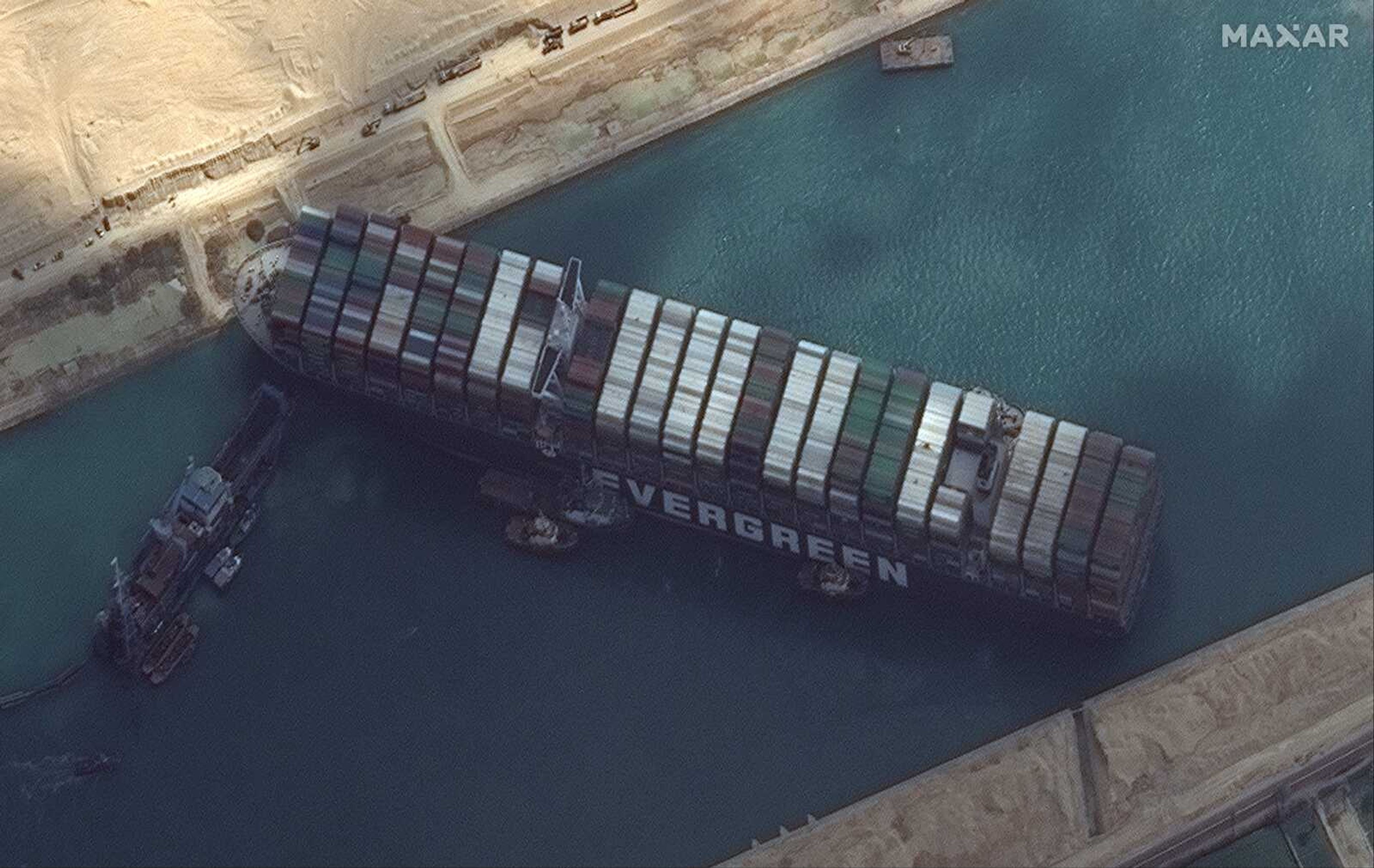

The Ever Given, owned by the Japanese firm Shoei Kisen KK, got wedged Tuesday in a single-lane stretch of the canal, about 3.7 miles north of the southern entrance, near the city of Suez.

A team from Boskalis, a Dutch firm specializing in salvaging, is working with the canal authority, using tugboats and a specialized suction dredger that is trying to remove sand and mud from around the port side of the bow. Egyptian authorities have prohibited media access to the site.

An attempt Friday to free it failed, said Bernhard Schulte Shipmanagement, the technical manager of the Ever Given. Plans are in the works to pump water from interior spaces of the vessel, and two more tugs should arrive by Sunday, the company said.

The Suez Canal Authority said it welcomed international assistance. The White House said it has offered to help Egypt reopen the canal. "We are consulting with our Egyptian partners about how we can best support their efforts," press secretary Jen Psaki said.

The canal authority released a video showing Lt. Gen. Osama Rabei inspecting efforts to free the Ever Given and telling workers: "Good luck, God willing."

An initial investigation showed the vessel ran aground due to strong winds and ruled out mechanical or engine failure as a cause, the company said. GAC, a global shipping and logistics company, had previously said the ship had experienced a power blackout, but it did not elaborate.

Bernhard Schulte said two canal pilots had been aboard the ship when it got stuck. Such an arrangement is customary, but the ship's captain retains ultimate authority over the vessel, according to shipping experts.

In addition to the over 200 vessels waiting near the canal, more than 100 ships were en route to the waterway, according to the data firm Refinitiv.

Apparently anticipating long delays, the owners of the stuck vessel diverted a sister ship, the Ever Greet, to head around Africa instead, according to satellite data.

Others also are being diverted to avoid the canal. The liquid natural gas carrier Pan Americas changed course in the mid-Atlantic, now aiming south to go around the southern tip of Africa, according to satellite data from MarineTraffic.com.

About 10% of world trade flows through the canal, which is particularly crucial for the transport of oil. The closure also could affect oil and gas shipments to Europe from the Middle East.

Oil markets are absorbing the disruption for now, said analyst Toril Bosoni.

"Oil inventories have been coming down but they are still relatively ample," he told The Associated Press, adding that he believes the impact might be more pronounced in the tanker sector than in the oil industry.

"We are not losing any oil supply but it will tie up tankers for longer if they have to go around" the tip of Africa, he said, which is roughly an additional two-week trip.

At the White House, Psaki added that the U.S. does see "some potential impacts on energy markets from the role of the Suez Canal as a key bidirectional transit route for oil. ... We're going to continue to monitor market conditions and we'll respond appropriately if necessary, but it is something we're watching closely."

Freeing the Ever Given is "quite a challenge" and could take five days to a week, .Capt. Nick Sloane, a maritime salvage expert who led the high-profile effort to salvage the cruise ship Costa Concordia in 2012 told the AP.

The Ever Given's location, size and large amount of cargo make the operation more complex, Sloane said. The operation should focus initially on dredging the bank and sea floor around it to get it floating again, rather than unloading its cargo, which could take weeks.

That's because the clock is also ticking structurally for the vessel, he added.

"The longer it takes, the worse the condition of the ship will become, because she's slowly sagging," said Sloane, vice president of the International Salvage Union. "So ships are designed to flex, but not to be kept at that position with a full load of cargo for weeks at a time. So it's not an easy situation."

International companies are preparing for the effect that the canal's blockage will have on supply chains that rely on precise deliveries of goods. Singapore's Minister of Transport Ong Ye Kung said the country's port should expect disruptions.

"Should that happen, some draw down on inventories will become necessary," he said on Facebook.

The backlog of vessels could stress European ports and the international supply of containers, already strained by the coronavirus pandemic, according to IHS Markit, a business research group. It said 49 container ships were scheduled to pass through the canal in the week since the Ever Given became lodged.

The delay could also result in huge insurance claims by companies, according to Marcus Baker, global head of Marine & Cargo at the insurance broker Marsh, with a ship like the Ever Given usually covered at between $100 million to $200 million.

Those trying to free the vessel want to avoid complications that could extend the canal closure, according to an Egyptian official at the canal authority. The official spoke on condition of anonymity as he was not authorized to talk to journalists.

Satellite and photos distributed by the canal authority show Ever Given's bow touching the eastern wall, while its stern appeared lodged against the western wall.

The Ever Given was involved in an accident in northern Germany in 2019, when it ran into a small ferry moored on the Elbe River in Hamburg. No passengers were on the ferry at the time and there were no injuries, but it was seriously damaged.

Hamburg prosecutors opened an investigation of the Ever Given's captain and pilot on suspicion of endangering shipping traffic, but shelved it in 2020 for lack of evidence, spokeswoman Liddy Oechtering told The Associated Press.

Oechtering also could not say what the investigation had determined the cause of the crash was, but officials at the time suggested that strong winds may have blown the slow moving cargo ship into the ferry.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.