Here's a vision of the not-so-distant future:n Microchips with antennas will be embedded in virtually everything you buy, wear, drive and read, allowing retailers and law enforcement to track consumer items -- and, by extension, consumers -- wherever they go, from a distance.

- A seamless, global network of electronic "sniffers" will scan radio tags in myriad public settings, identifying people and their tastes instantly so that customized ads, "live spam," may be beamed at them.

- In "Smart Homes," sensors built into walls, floors and appliances will inventory possessions, record eating habits, monitor medicine cabinets -- all the while, silently reporting data to marketers eager for a peek into the occupants' private lives.

Science fiction?

In truth, much of the radio frequency identification technology that enables objects and people to be tagged and tracked wirelessly already exists -- and new and potentially intrusive uses of it are being patented, perfected and deployed.

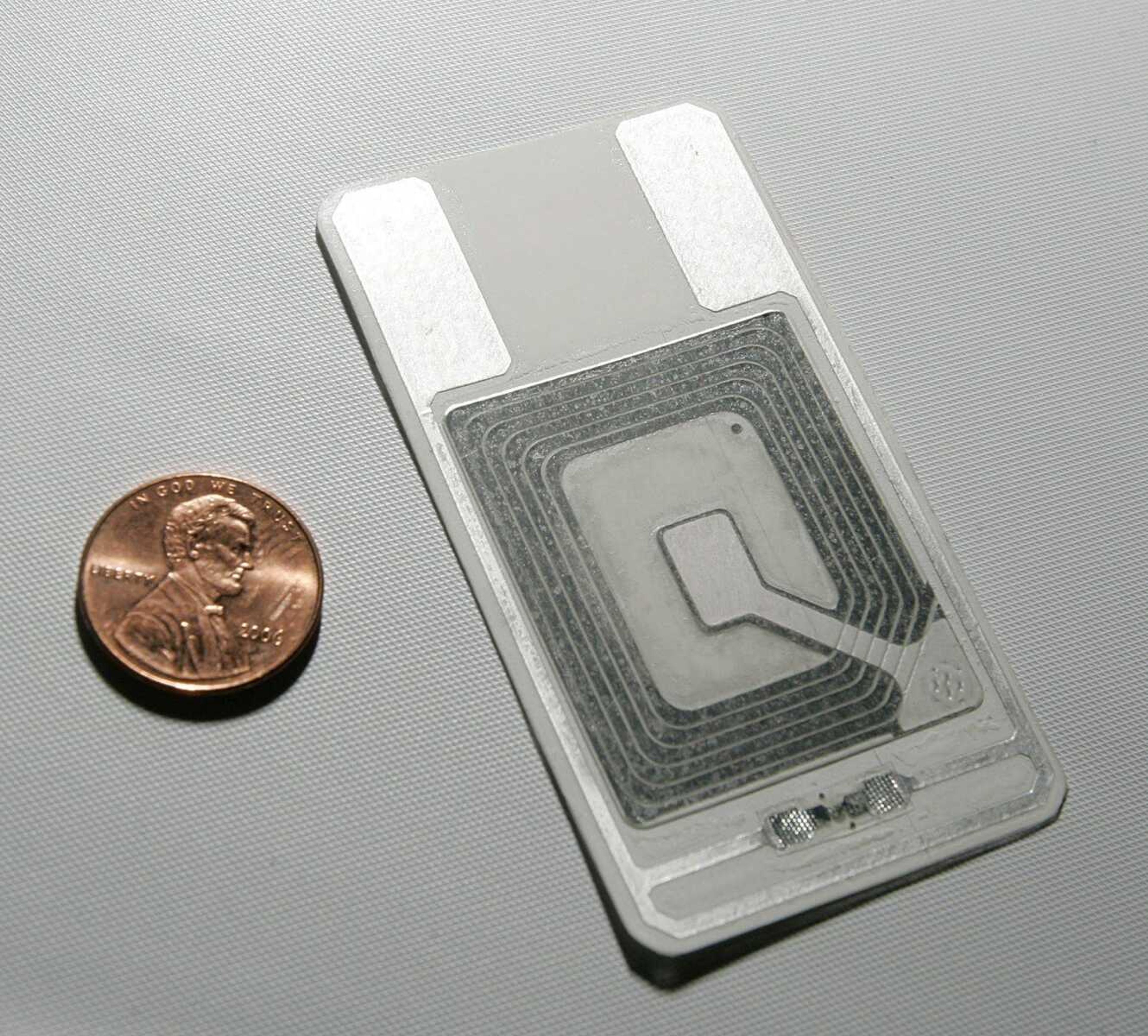

Some of the world's largest corporations are vested in the success of RFID technology, which couples highly miniaturized computers with radio antennas to broadcast information about sales and buyers to company databases.

Already, microchips are turning up in some computer printers, car keys and tires, on shampoo bottles and department store clothing tags. They're also in library books and "contactless" payment cards (such as American Express' "Blue" and ExxonMobil's "Speedpass.")

Improving efficiency

Companies say the RFID tags improve supply-chain efficiency, cut theft, and guarantee that brand-name products are authentic, not counterfeit. At a store, RFID doorways could scan your purchases automatically as you leave, eliminating tedious checkouts.

At home, convenience is a selling point: RFID-enabled refrigerators could warn about expired milk, generate weekly shopping lists, even send signals to your interactive TV, so that you see "personalized" commercials for foods you have a history of buying.

The problem, critics say, is that microchipped products might very well do a whole lot more.

With tags in so many objects, relaying information to databases that can be linked to credit and bank cards, almost no aspect of life may soon be safe from the prying eyes of corporations and governments, said Mark Rasch, former head of the computer-crime unit of the U.S. Justice Department.

Using sniffers, companies can invisibly "rifle through people's pockets, purses, suitcases, briefcases, luggage -- and possibly their kitchens and bedrooms -- anytime of the day or night," said Rasch, now managing director of technology at FTI Consulting Inc., a Baltimore-based company.

Spying worries

In an RFID world, "You've got the possibility of unauthorized people learning stuff about who you are, what you've bought, how and where you've bought it ... It's like saying, 'Well, who wants to look through my medicine cabinet?"'

He imagines a time when anyone from police to identity thieves might scan locked car trunks or home offices from a distance. "Think of it as a high-tech form of Dumpster diving," said Rasch, who's also concerned about data gathered by "spy" appliances in the home.

"It's going to be used in unintended ways by third parties -- not just the government, but private investigators, marketers, lawyers building a case against you ..."

Presently, the radio tag most commercialized in America is the so-called "passive" emitter, meaning it has no internal power supply. Only when a reader powers these tags with a squirt of electrons do they broadcast their signal, indiscriminately, within a range of a few inches to 20 feet.

Not as common, but increasing in use, are "active" tags, which have internal batteries and can transmit signals, continuously, as far as low-orbiting satellites. Active tags pay tolls as motorists zip through tollgates; they also track wildlife.

Retailers and manufacturers want to use passive tags to replace the bar code, for tracking inventory. These radio tags transmit Electronic Product Codes, number strings that allow trillons of objects to be uniquely identified. Some transmit specifics about the item, such as price, though not the name of the buyer.

RFID profiling

However, "once a tagged item is associated with a particular individual, personally identifiable information can be obtained and then aggregated to develop a profile," the U.S. Government Accountability Office concluded in a 2005 report on RFID.

Federal agencies and law enforcement already buy information about individuals from commercial data brokers, companies that compile computer dossiers on individuals from public records, credit applications and other sources, then offer summaries for sale. These brokers, unlike credit bureaus, aren't subject to provisions of the Fair Credit Reporting Act of 1970, which gives consumers the right to correct errors and block access to their personal records.

That, and the ever-increasing volume of data collected on consumers, is worrisome, said Mike Hrabik, chief technology officer at Solutionary, a computer-security firm in Bethesda, Md. "Are companies using that information incorrectly, and are they giving it out inappropriately? I'm sure that's happening. Should we be concerned? Yes."

The recent growth of the RFID industry has been staggering: From 1955 to 2005, cumulative sales of radio tags totaled 2.4 billion; last year alone, 2.24 billion tags were sold worldwide, and analysts project that by 2017 cumulative sales will top 1 trillion -- generating more than $25 billion in annual revenues for the industry.

Privacy concerns, some RFID supporters say, are overblown. One, Mark Roberti, editor of RFID Journal, said the notion that businesses would conspire to create high-resolution portraits of people is "simply silly."

Corporations know Americans are sensitive about privacy, he said. As American Express spokeswoman Judy Tenzer said: "Security and privacy are a top priority for American Express in everything we do."

But industry documents suggest a different line of thinking, privacy experts say.

A 2005 patent application by American Express itself describes how RFID-embedded objects carried by shoppers could emit "identification signals" when queried by electronic "consumer trackers." The system could identify people, record their movements, and send them video ads that might offer "incentives" or "even the emission of a scent."

RFID readers could be placed in public venues, including "a common area of a school, shopping center, bus station or other place of public accommodation," according to the application, which is still pending.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.