Putting out the fire

In her worst moment, Dee Dee Dockins wished someone -- anyone -- would take her baby away. That was after losing her first child -- a girl -- at 3 days old. After waiting for three years to try again, only to find out her second baby suffered from a heart defect as well. After a traumatic pregnancy. After watching her newborn son's heart beat outside his chest for four days. After the heart surgery that saved 6-month-old Jonathan's life...

In her worst moment, Dee Dee Dockins wished someone -- anyone -- would take her baby away.

That was after losing her first child -- a girl -- at 3 days old. After waiting for three years to try again, only to find out her second baby suffered from a heart defect as well. After a traumatic pregnancy. After watching her newborn son's heart beat outside his chest for four days. After the heart surgery that saved 6-month-old Jonathan's life.

After they finally returned home to Jackson. After she discovered that life can always get worse.

n

Reflux.

The word sounds innocent enough. There are regular advertisements on TV for medications to prevent and ease it; no big deal.

Dee Dee and Jamey Dockins had never given the disease a thought. But it was reflux, not their baby's four-pronged heart defect, that eventually brought the Jackson couple to their breaking point.

n

Dee Dee Dockins never considered herself motherhood material; she was a career woman.

At 35, she and husband Jamey lost their first baby -- a girl born with severe birth defects. After three years trying to come to terms with that loss, Jonathan was conceived.

Twenty weeks into her pregnancy, the couple was told Jonathan had an abnormal heart. At 28 weeks, the 38-year-old Dockins began having contractions and spent the next month at St. John's Hospital in St. Louis.

On one side of a piece of notebook paper, she made a list of items she needed for a baby shower. On the other side, she planned her baby's funeral, just in case.

On Oct. 13, 2005, Jonathan Lee Dockins was born, then immediately rushed to Children's Hospital and put on life support.

He was two weeks premature and born with a ventricular septum defect. Basically, blood pumped in and out of his heart on the same side. A hole in his tiny heart basically kept him alive, allowing the blood to pass in the right side, over to the left side to be oxygenated, and back out the right side. His heart worked most of the time, but when Jonathan became upset, the hole in his heart constricted and the blood could not be oxygenated. On Feb. 13. -- at 4 months old -- Jonathan had open heart surgery to fix the defect.

The surgery was more complicated than the pediatric cardiologist originally thought. Jonathan's heart was rotated. The working side was on top, so the surgeon was forced to cut through it to reach the troublesome right side. Afterwards, his heart was so swollen it didn't fit into his chest. The Dockins watched their child's plastic-wrapped heart beat outside his chest for four days. But Jonathan made it through, and his doctors began calling him the "miracle baby."

After surviving the heart surgery, the Dockins were certain they were on the path to normalcy. But then they hit another roadblock, unexpected and yet somehow more severe than even the heart defect.

n

Dee Dee Dockins has come to despise infant/parenthood magazines.

The stories in those magazines; the smiling babies on the cover are something she knows nothing about.

"People say, 'Oh, is your baby a little fussy?' No, a baby with reflux screams in pain. A baby with reflux would rather starve itself than eat, defying one of nature's basic instincts," Dockins said. "This isn't just babies spitting up or having a little heartburn. It's a real problem."

A problem that can be difficult to diagnose, has no established cause, and seems to be growing among newborns in the United States.

"We had seven different opinions on what he has," said Dockins. "With reflux, everyone is just stabbing in the dark."

The National Institute of Health lists spitting, vomiting, coughing, irritability, poor feeding and blood in stools as symptoms for gastroesophageal reflux (GER) in infants. The NIH estimates that more 50 percent of all babies experience reflux in the first three months of life. Most symptoms disappear between 12 and 18 months of age.

But among a smaller group of babies, the symptoms can be more severe. Poor growth due to inability to hold down food. Refusing to feed due to pain. Blood loss from acid burning the esophagus. Breathing problems.

Jonathan Dockins falls into the latter category.

The family tried medicines like Prevacid and Prilosec. They tried a variety of diets. They bought a Hoover spot remover to clean up Jonathan's violent projectile vomiting.

But no matter what Dee Dee and Jamey Dockins tried, their baby either would not eat or could not keep what little he ate in his stomach. Jonathan was starving himself.

He spent 44 days of the first three and half months of his life in a hospital. Twenty eight of those days were because of reflux. The remaining 16 were because of the heart defect.

He screamed almost constantly. He didn't sleep; neither did his parents.

Eventually, they were forced to put him on a feeding tube.

"I reached a point where I wanted to say, 'Someone else please take this baby,'" said Dockins.

n

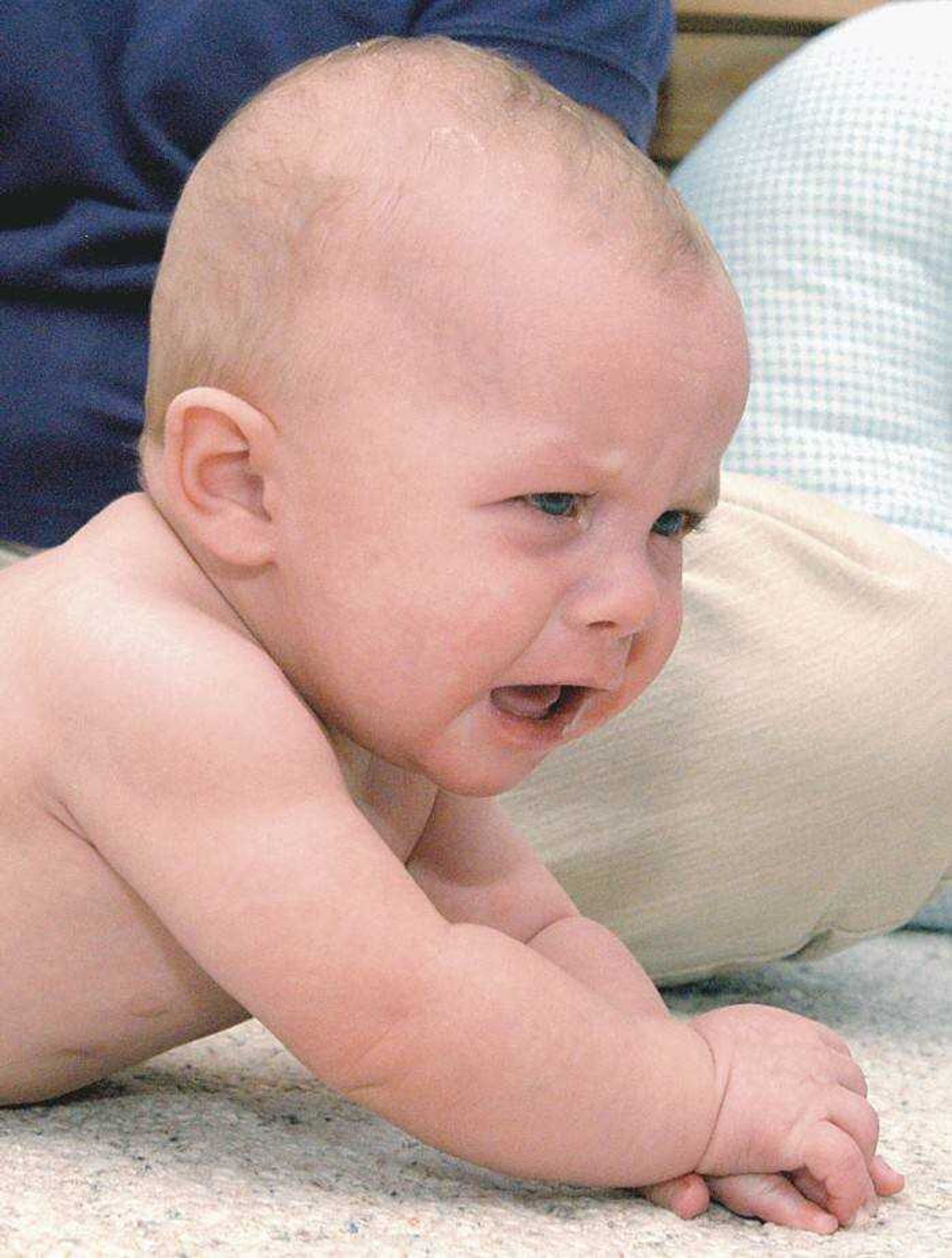

Today, Jonathan Dockins looks a healthy, happy baby. Almost like the kind you see on the cover of those parenthood magazines.

The seven-inch-long purple scar that splits his small chest is hidden behind a striped blue jumper. He eats without a feeding pump now, though the task is still troublesome. The best chance of him keeping food down comes during his sleep, so his parents get up for three feeding sessions throughout the night.

But today, at least, he smiles.

The change in Jonathan came suddenly, after a visit to a local chiropractor.

Over the years, Dr. Roy Meyer has seen more and more infants and children in his practice, for all sorts of reasons -- diseases such as irritable bowel syndrome and reflux included.

Over a stretch of three or four visits, Meyer treated Jonathan with several techniques, including mayofacial release and CranioSacral therapy (therapy that works with a physiological body system called the craniosacral system, which includes membranes and cerebrospinal fluid that surround and protect the brain and spinal cord).

The mayofacial release was intended to ease the stress of tissue pulling down the baby's diaphragm. Meyer said it's important that all potential medical problems be evaluated before such work is done on an infant, but believes his treatment has helped children who suffer from both reflux and colic.

"It worked marvelously well for this child," said Meyer. "He had this problem every day of his life since he came onto this planet."

The day after Meyer's treatment, Jonathan stopped vomiting.

The Dockins believe that treatment helped their son, though there's a chance he's simply begun to outgrow the problem.

Either way, they're thankful. But Dee Dee Dockins' frustration over getting a diagnosis, finding treatment and dealing with peoples' ignorance of how severe reflux can be has not faded.

"Every doctor we talked to had a different opinion. My advice to other parents is don't settle on one diagnosis. Find some information on your own," said Dockins. "And forget the guilt. There may be days when you don't want to be around your baby, but that's okay."

cmiller@semissourian.com

335-6611, extension 128

GRAPHIC

By the numbers: Reflux statistics

About one third of the adult population experiences reflux at least once a month and about 10 percent of the population experiences reflux weekly or daily. As well, at least 50 percent of infants are born with some degree of reflux simply from immaturity of the lower esophageal sphincter. Most of these infants will not have complications and will outgrow it before they are a year old. It is estimated that about 3 percent will not outgrow it and will experience the more serious complications related to GERD. -- www.infantrefluxdisease.com

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.