Sharing a success story

During a conversation, Taylor Crowe stares you in the eye almost relentlessly. Maintaining eye contact is one of many social skills people tend to take for granted, but for a person with autism, it often proves extremely difficult. "We practiced that and practiced that and practiced that," said David Crowe, Taylor's father. ...

During a conversation, Taylor Crowe stares you in the eye almost relentlessly.

Maintaining eye contact is one of many social skills people tend to take for granted, but for a person with autism, it often proves extremely difficult.

"We practiced that and practiced that and practiced that," said David Crowe, Taylor's father. He and Taylor -- who was diagnosed with autism in 1985 -- now have a program called "Growing Up with Autism," which they presented in front of more than 100 people Monday night at Southeast Missouri Hospital.

Autism covers a spectrum of developmental disorders characterized by impaired social interaction and communication difficulties, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

"We made [eye contact] a social goal," David said. He and Taylor, now 26, had staring contests and played games that required eye contact.

The goals Taylor's parents set for him were all focused on increasing normal social skills. They enrolled him in youth baseball and church groups that challenged him to interact in social situations.

"Unless he has those base social skills, he'll never be employable," David said. "He'll never be able to function in society."

Their practices paid off. Taylor recently graduated from the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia, Calif., the walls of which have seen the likes of John Lasseter, who started Pixar, and Steven Hillenburg, who pens "SpongeBob SquarePants," and now Taylor Crowe.

Taylor aired one of his short animated films at the program Monday night. "Growing Up with Autism" is one of four speeches Taylor gives to educate people on autism and how to interact with those diagnosed with it.

"You never know when you'll meet someone who has that disability," Taylor said.

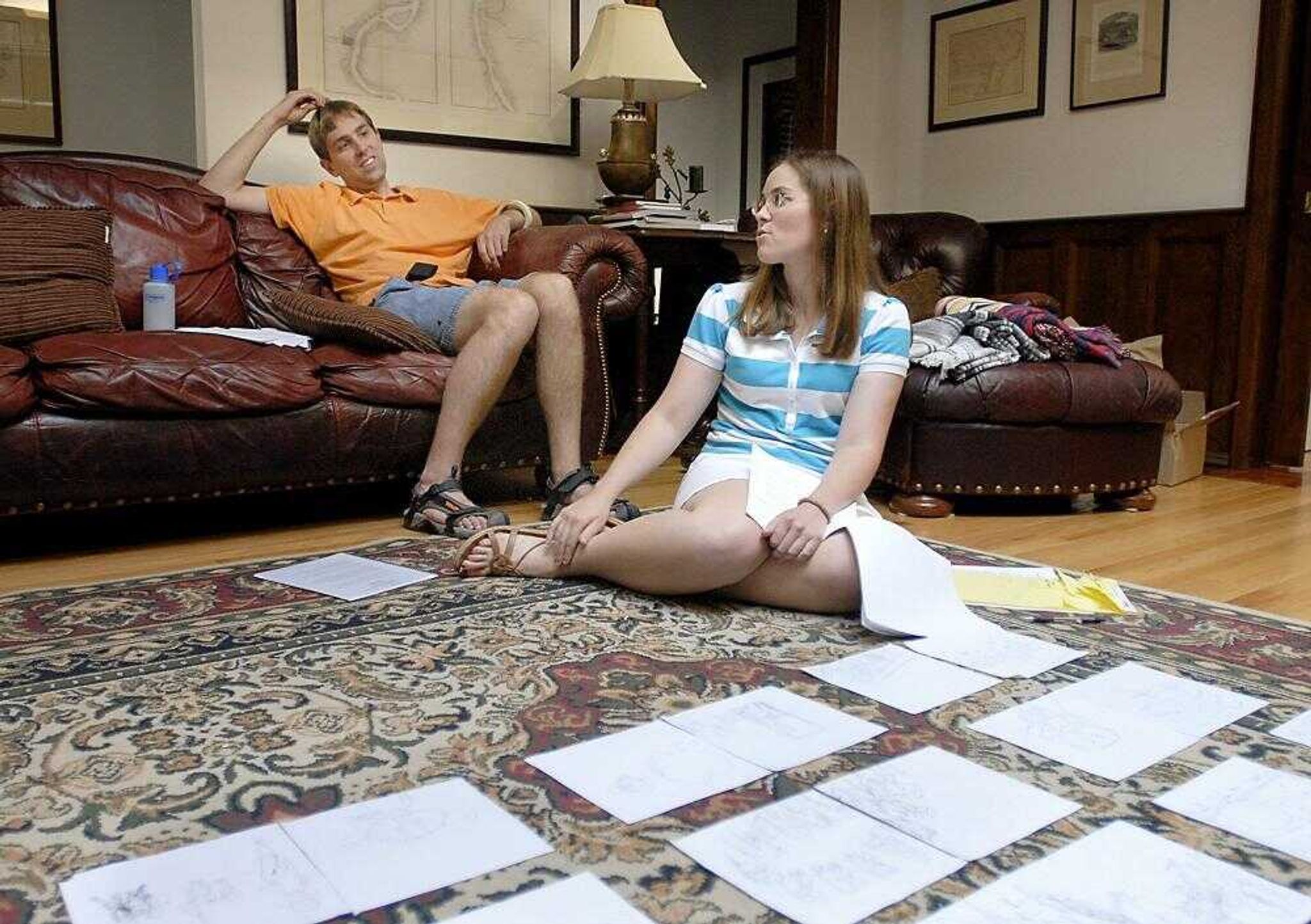

Taylor has been giving speeches on autism for years and hopes to soon publish a children's book about the disorder. He and Leah Ulrich have been working on the book for the past two summers and hope to finish it in September.

They hope the book will provide education on what autism is and how to interact with children who have it, Ulrich said.

The book, "My Friend with Autism," shows a boy named Alex who sometimes throws tantrums or gets extremely upset at situations while at other times he is a normal child, playing on the swings during recess.

It shows, Ulrich said, "There is a person inside there. We just have to get more of that out of him."

Ultimately, the two want to see the book turn into a series that follows Alex through the years to show the problems and successes he has.

"They're all things I experienced," Taylor said about the instances he illustrated for the book. "This book is sort of about my life."

Taylor was not always the speaker and friendly artist who breaks the ice by telling new people the exact day of the week on which they were born. When he was younger, he could not socialize like other children.

His parents realized they needed to take an active role in bringing out his personality.

They adopted a "Circle of Friends" approach and enlisted children from Taylor's classes to help him along and provide support when bullies threatened him or if Taylor needed help knowing what to do in a situation.

"I learned how to be a kid by being around other kids," Taylor said in an informational DVD he and his father made.

The circle of friends helped Taylor know if someone was joking or being sarcastic.

"Don't say anything that isn't true," Taylor advised.

"Taylor takes everything very literally," Ulrich said. She once commented in traffic that the cars "were really flying," and Taylor looked to the sky.

Taylor also had speech and occupational therapy when growing up.

Occupational therapy is often employed to help with the sensory problems autistic children often endure.

Their taste, smell or touch senses can be either heightened or lowered as a result of the disorder.

"Being touched was horrible," David said. Sometimes even the label inside a T-shirt can be unbearable for individuals with autism, he said.

Many times, speech therapy is needed because the child's ability to speak is lost or impaired, according to the NINDS.

Taylor's speech has improved to the point of an experienced and engaging public speaker.

"I couldn't wait to get up here to hear him," said Jennifer Barnett, who lives in West Plains, Mo.

She and her husband John believe their son has pervasive developmental disorder, a form of high-functioning autism.

"It gives you hope, " she said about Taylor's story.

The Barnett's son Scout, 10, has memorized the street map to their city and can play against himself on Mario Kart using both controllers simultaneously. Scout is in the 4th grade and attends public school in a normal classroom environment.

"They need that social interaction because that's what they're lacking," Barnett said.

The social skills of autistic individuals can be practiced, though, as evidenced by Taylor.

"He has come a long way from when I first met him," Ulrich said.

"There's been a profound change in social skills and confidence level. It's an extreme difference."

Family and friends were all Taylor had to help him learn social skills.

Now, some children with high-functioning autism or Asperger's disorder can now get help through The Tailor Institute in Cape Girardeau. The insititute is a not-for-profit foundation in Cape Girardeau that works with individuals who are gifted or have a savant skill, like art, music or math.

"It is unique in that we are addressing a very small percentage of the overall autistic spectrum," said Elaine Beussink, incoming director of the institute effective in September. Beussink has been the Cape Girardeau Public Schools in district autism consultant for the last four years.

Much of the research surrounding autism has been concentrated on the low-functioning forms of the disorder. The Tailor Institute caters to high-functioning individuals to help them absorb into society.

"The staff vision is that we will be able to solidify the program's module so that it could be available at some point for replication by other agencies," Beussink said.

The program tries "to capitalize on [autistic individuals[']] strengths to improve the overall quality of life," she said.

It helps them to use their talent for financial gain, she said, whether that's working for someone else or using their skills in an entrepreneurship opportunity.

charris@semissouiran.com

335-6611, extension 246

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.