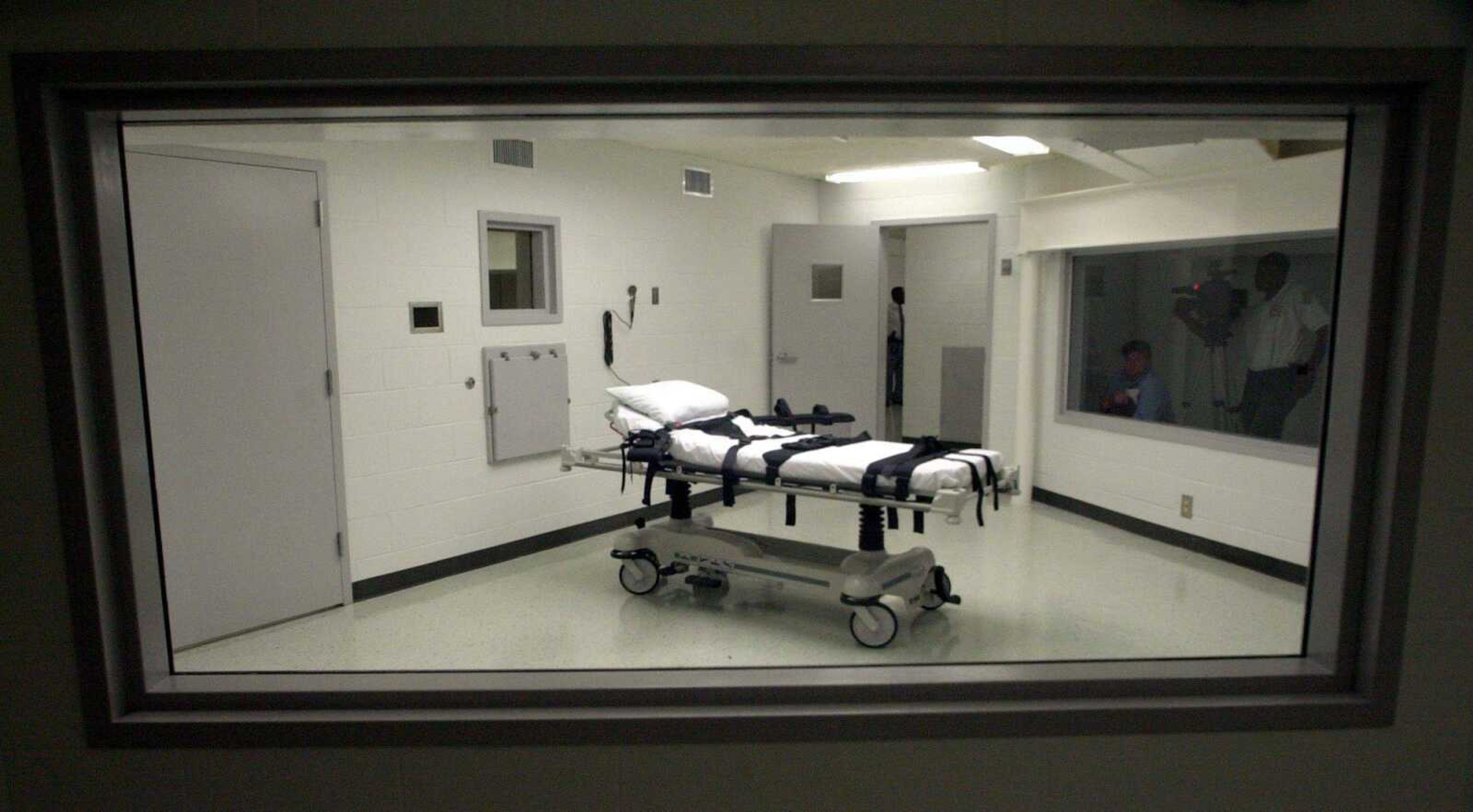

Supreme Court appears divided over drugs used in lethal injections

WASHINGTON -- The Supreme Court appeared divided Monday over whether the drugs commonly injected to execute prisoners risk causing excruciating pain in violation of the Constitution. Several justices indicated a willingness to preserve the three-drug cocktail that is authorized by three dozen states that allow executions. Such a decision would allow lethal injections, on hold since late September, to resume quickly...

~ Two Kentucky death-row inmates want the court to order a switch to a single drug for the injection.

WASHINGTON -- The Supreme Court appeared divided Monday over whether the drugs commonly injected to execute prisoners risk causing excruciating pain in violation of the Constitution.

Several justices indicated a willingness to preserve the three-drug cocktail that is authorized by three dozen states that allow executions. Such a decision would allow lethal injections, on hold since late September, to resume quickly.

Justice Antonin Scalia said states have been careful to adopt procedures that do not seek to inflict pain and should not be barred from carrying out executions even if prison officials sometimes make mistakes in administering drugs. "There is no painless requirement" in the Constitution, Scalia said. Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito also indicated their support for the states' procedures.

Other members of the court, who have raised questions about lethal injection in the past, said they are bothered by the procedures used in Kentucky and elsewhere in which three drugs are administered in succession to knock out, paralyze and kill prisoners.

The argument against the three-drug protocol is that if the initial anesthetic does not take hold, a third drug that stops the heart can cause excruciating pain. The second drug, meanwhile, paralyzes the prisoner, rendering him unable to express his discomfort.

"I'm terribly troubled by the fact that the second drug is what seems to cause all the risk of excruciating pain and seems to be almost totally unnecessary," said Justice John Paul Stevens.

Justice Anthony Kennedy, who often plays a decisive role on the closely divided court, gave little indication of his views.

The case before the court comes from Kentucky, in which two death-row inmates are not asking to be spared execution or death by injection. Instead, they want the court to order a switch to a single drug, a barbiturate, that causes no pain and can be given in a large enough dose to cause death.

At the least, they are asking for tighter controls on the three-drug process to ensure that the anesthetic is given properly. A decision should come by late June.

Justice Stephen Breyer seemed to capture the discomfort of the court, which has upheld the constitutionality of capital punishment.

"There is a risk of human error generally where you're talking about the death penalty, and this may be one extra problem," Breyer said. "But the question here is can we say that there is a more serious problem here than with other execution methods?"

Donald Verrilli, a Washington lawyer who is a veteran of capital cases, offered the court examples of executions in California and North Carolina in which inmates appeared to suffer pain as they were being put to death.

He said the best way to avoid repetition was to switch to a single drug, as veterinarians commonly use in putting animals to sleep.

"The risk here is real," Verrilli said. "That is why in the state of Kentucky it is unlawful to euthanize animals the way" the state executes inmates, he said.

Roy Englert, who typically argues business cases before the Supreme Court, said on behalf of Kentucky that the one-drug method has never been used in executions. The Bush administration also took Kentucky's side.

Englert also defended the state's practices as humane. Kentucky regularly trains its execution team and employs an experienced worker to insert the intravenous lines through which the drugs are administered, he said.

The state's lone execution by lethal injection did not present any obvious problems, both sides agreed.

The court may decide the Kentucky case is not the right one to settle the constitutionality of the three-drug procedure and leave that issue for another death penalty case.

Justice David Souter, however, urged his colleagues to take the time necessary to issue a definitive decision about the three-drug method in this case, even if it means sending the case back to Kentucky for more study by courts there.

Scalia, however, said such a move would mean "a national cessation of executions" that could last for years. "You wouldn't want that to happen," he said.

Recent executions in Florida and Ohio took much longer than usual, with strong indications that the prisoners suffered severe pain in the process. Workers had trouble inserting the IV lines that are used to deliver the drugs.

Lined up in front of the court waiting to attend the arguments, college students Jeremy Sperling and Gira Joshi said they oppose the death penalty, but regard making executions less painful and more humane as a worthy goal.

"You have the right to die with dignity," said Joshi, a political science and religion major at New Jersey's Rutgers University. Sperling, a psychology and religion major at New York University, said serving a life prison term is the appropriate alternative to the death penalty.

After Monday's court session, the brother of a victim of one Kentucky prisoner said the case already has dragged on too long. Powell County Sheriff Steve Bennett was shot to death by Ralph Baze in 1992.

"Ralph Baze was tried. The death penalty was what he got and he chose lethal injection," said Orville Bennett of Beattyville, Ky. "And we need to just get this over with."

The case is Baze v. Rees, 07-5439.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.