Trump's vow to infrastructure being questioned

WASHINGTON -- It's not at all clear President-elect Donald Trump's plans to spend massively on infrastructure are going to unfold as he promised. Trump made rebuilding the nation's aging roads, bridges and airports very much part of his job-creation strategy in the presidential race...

WASHINGTON -- It's not at all clear President-elect Donald Trump's plans to spend massively on infrastructure are going to unfold as he promised.

Trump made rebuilding the nation's aging roads, bridges and airports very much part of his job-creation strategy in the presidential race.

But lately, lobbyists have begun to fear there won't be an infrastructure proposal at all, or at least not the grand plan they'd been led to expect.

From the day he entered the presidential race to the moment he declared victory, Trump pledged an infrastructure renewal.

He cited decaying bridges, potholed roads and airports such as New York's LaGuardia he said reminded him of the "third world."

Trump or his campaign also mentioned schools, hospitals, pipelines, water treatment plants and the electrical grid as part of a job-creation strategy that would make the U.S. "second to none."

It was a rare area in which House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi and other Democrats hoped for common ground with the president-elect. The possibility of a major infrastructure spending plan is one of several factors that have fueled the recent run-up in stock prices.

But did he mean it?

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell tried to tamp down expectations last week, saying he wants to avoid "a $1 trillion stimulus."

And Reince Priebus, who will be Trump's chief of staff, said in a radio interview the new administration will focus in its first nine months with other issues such as health care and rewriting tax laws. He sidestepped questions about the infrastructure plan.

In a post-election interview with The New York Times, Trump seemed to back away, saying infrastructure won't be a "core" part of the first few years of his administration. But he said there still will be "a very large-scale infrastructure bill."

He acknowledged he didn't realize during the campaign New Deal-style proposals to put people to work building infrastructure might conflict with his party's small-government philosophy.

"That's not a very Republican thing -- I didn't even know that, frankly," he said.

Since the election, Trump has backed away -- or at least suggested flexibility -- on a range of issues that energized his supporters during the campaign, including his promises to prosecute Hillary Clinton, pull out of the Paris climate-change accord and reinstitute waterboarding for detainees.

Trump transition officials didn't respond to a request for comment.

The mixed signals on infrastructure have lobbyists and lawmakers puzzled.

"We're worried," said Brian Turmail, a spokesman for the Associated General Contractors of America, which represents more than 26,000 construction companies and 10,500 service providers and suppliers.

"Are we hearing signs that people just don't know what the plan is?" he asked. "Or signs that people don't want any kind of plan? We don't know the answer."

Lobbyists have responded by flooding the Trump transition team with memos, lining up meetings and pitching their proposals to what they hope will be a more receptive Congress.

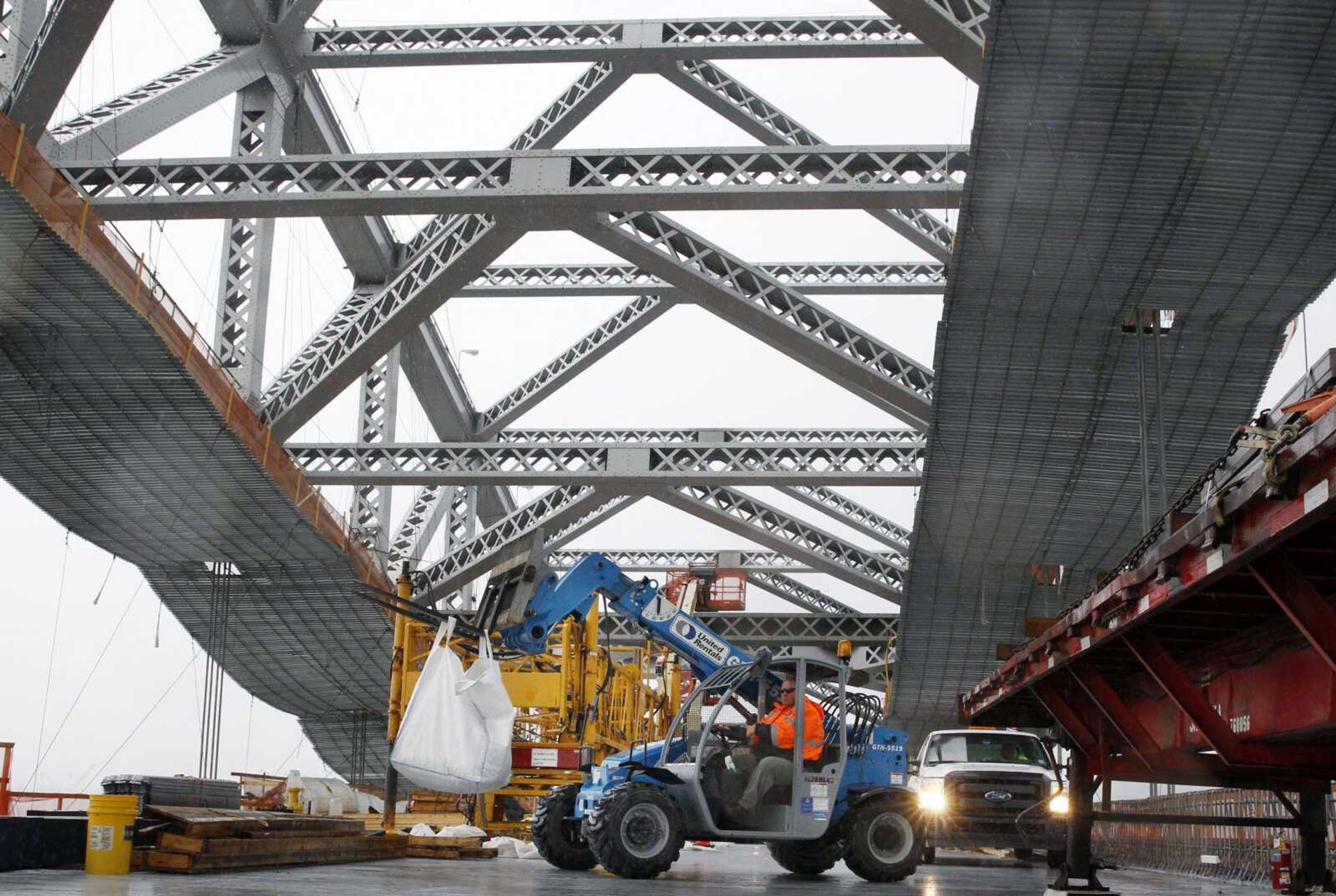

Trade associations are urging local members to seek their senators and House members while they're home for the holidays. The contractors' association held a news conference in front of a bridge construction project in Little Rock, Arkansas.

The American Road and Transportation Builders Association has given members form letters to send their lawmakers, while quietly floating a plan for new transportation fees to provide reliable sources of additional income for the federal Highway Trust Fund.

Leaders of the U.S. Conference of Mayors emphasized their support for an infrastructure program in a recent meeting with Trump and urged him to protect the municipal bond tax exemption, one of the primary ways localities raise money for projects.

The Airports Council International-North America is lobbying to raise the limit on fees airports charge airline passengers. The money goes to renovate or expand terminals and increase the number of gates.

Trump's campaign pitch for infrastructure improvements included few details. A paper circulated after the election recommends using $137 billion in federal tax credits to generate $1 trillion in private-sector infrastructure investment over a decade. To offset the cost of the credits, U.S. corporations would be encouraged to bring home profits that they have parked overseas to avoid taxes, in exchange for a lower tax rate. But private investors are typically interested only in projects that create revenue, such as tolls, so that they can recoup their investments.

What states and communities need most is more direct spending, rather than tax credits, to help pay for upkeep and replacement of existing roads, bridges and transit systems, said Bud Wright, executive director of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. "Those aren't necessarily projects that lend themselves to generating revenue," he said.

It's also possible tax credits would provide a windfall to investors in existing projects while failing to generate new ones.

Some lawmakers from both parties are urging the creation of a federal "infrastructure bank" to make low-cost loans to projects.

"Everybody is putting together their Christmas lists for what they want to see in an infrastructure bill," said Kevin Gluba, executive director of the Alliance for Innovation and Infrastructure. "The biggest question: Who is going to pay for it? Many of the ideas floating around are far too pricey to make into law."

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.