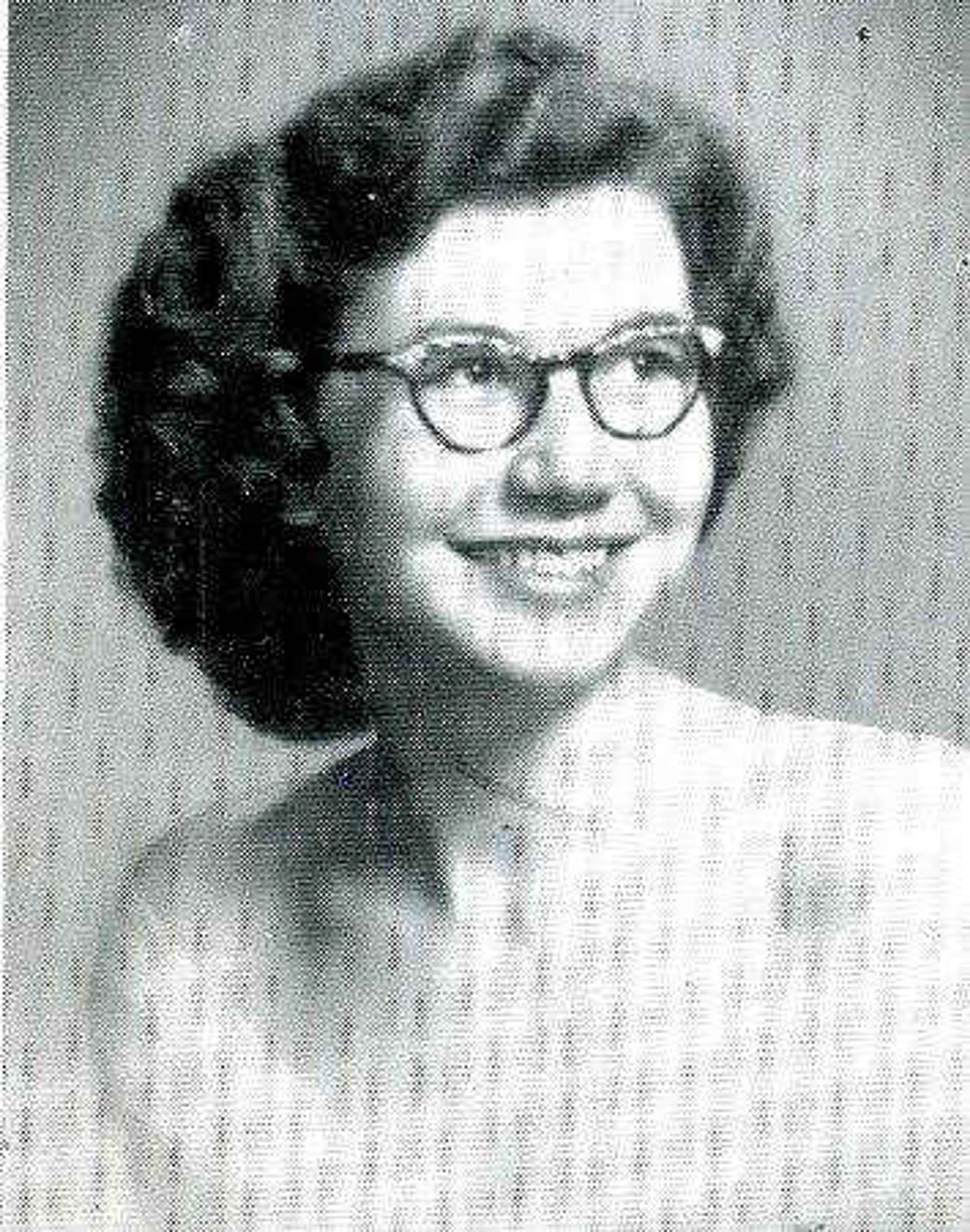

Unsolved cases: Bonnie Huffman

The smoking gun is made of plastic. An unnamed witness who claims to know what happened that night is afraid to talk. And the physical evidence is long gone. The question of who killed Bonnie Huffman, a pretty young schoolteacher whose body was discovered 55 years ago in an overgrown drainage ditch in Cape Girardeau County, has been hailed as one of Missouri's most baffling unsolved murder mysteries...

The smoking gun is made of plastic. An unnamed witness who claims to know what happened that night is afraid to talk. And the physical evidence is long gone.

The question of who killed Bonnie Huffman, a pretty young schoolteacher whose body was discovered 55 years ago in an overgrown drainage ditch in Cape Girardeau County, has been hailed as one of Missouri's most baffling unsolved murder mysteries.

For 15 years, what's left of the Huffman homicide case file has sat in a cardboard box underneath Sgt. Eric Friedrich's desk in the criminal investigations office at the Cape Girardeau County Sheriff's Department.

Old, dog-eared police memoranda and dozens of yellowed polygraph transcripts are the only remaining keys to the unsolved murder.

Every few months, someone will call Friedrich offering information they claim could unravel the 54-year-old mystery of the young schoolteacher found curled up with her neck broken near an open culvert along Route N just north of Delta.

On July 3, 1954, Huffman's little 1938 Ford was found parked in the middle of Route N, six miles from her home, just two miles from the overgrown ditch where a strong odor alerted an Allenville couple to the site of her body about 60 hours later.

Since then, numerous suspects have been interviewed and many have died, yet authorities are no less mystified by the case, nor any closer to shedding light on what Huffman went through between the hours she left her home to see a movie with friends, and the discovery of her body in the weeds the following day.

Most recently, a Texas woman contacted Friedrich, saying she'd become aware that one of her late relatives, before his death in 1998, had confessed to the rape and murder of a woman near Delta, but like every other tip, proving it true seems nearly impossible.

Every time the case resurfaces in the media, the cycle repeats itself: A few tips will roll in, and Friedrich will drag out the box of aging documents and drop everything to run down the new lead.

But so far, nothing has panned out.

"We try to keep it in the news because you never know when that one's going to count," said Wanda Ross, Huffman's niece.

Like Friedrich, Ross knows the frustration of receiving vague tips from callers who won't identify themselves.

They usually say they know who did it but can't tell her, she said.

Ross has even tried listing her number in the newspaper, letting tipsters know they can call her if they aren't comfortable talking to police.

"None of the tips seem to hold any water," she said.

Still, when a "good, hot lead" does cross his desk, Friedrich says he'll chase it as far as it can go, but it does tend to get frustrating.

He still believes that a 2004 letter sent from Florida contained such detailed description that it had to have come from someone who had been at the scene of the killing that night.

The writer recalled driving back from a dance that evening and seeing a car stopped at the curve of Route N about a half-mile from Delta.

"Back then, people would stop to help someone. I did," the person wrote.

When the writer pulled over, two men began hollering for that person to get out, and one tried to grab the driver and pull them out of the car, the letter said.

"Why I tried to help I will never know, because without the help from God I would have been killed," the person wrote.

While the men struggled to get into the car, the person managed to get the clutch in and shift, only to have the two assailants rush to their car and try to block the road.

The letter included a roughly drawn but accurate map of the area near where Huffman's body was found. Friedrich noted that it had been mailed to 40 S. Sprigg St., the address of the Cape Girardeau Police Department, where Huffman's body was taken after its discovery.

Most of what was it the letter was "right on the money," Friederich said, including the fact that there had been a dance nearby in Ancell that night.

Now, four years after the letter worked its way to Cape Girardeau, the section of the sheriff's department Web site dedicated to the county's unsolved homicides reads "unknown from Florida, we received letter. Thank You. Please Call," with the promise of anonymity.

Just about every year, Friedrich has resubmitted a latent fingerprint found on Huffman's car to AFIS, the national database containing prints of convicted felons, but so far, like everything else in the case, no hits have been returned.

Bonnie's disappearance

Temperatures soared past 100 degrees the week Huffman vanished as a blistering heat wave blanketed Cape Girardeau.

Huffman left her mother's home in Bollinger County around 3 p.m. July 2, 1954, to see a movie in Cape Girardeau with Mary Lou and Cramer Bess, friends of hers who had recently gotten married.

The willowy brunette was 20 years old. She had just finished teaching her third term at Buckeye School near Old Appleton and was preparing to start an office job at the Missouri Utilities Co.

She and Mary Lou Bess had become close friends when Huffman taught Bess' younger brother in school, Bess said.

Douglas Hiett, Huffman's boyfriend of four years, had just returned from military service in Korea.

Though the couple was not officially engaged, Huffman had thought they would marry, but Hiett canceled their plans together that evening, and told her he wanted to break things off.

Huffman was upset and talked about Hiett a lot that evening, Bess recalled.

After the movie at the Broadway Theater, they'd gone to Wimpy's drive in to get a bite to eat, and stopped at Cape Rock to watch the barges float by for a while.

Then Huffman asked if they could drive past one of the taverns, near the bridge, presumably to see if Hiett's car was outside, Bess said.

"It used to be kind of a rough joint," Bess said.

Her husband would not let them go inside the bar, and they dropped Huffman off at her car, which she'd just gotten overhauled, Bess said.

"That was the last time I saw Bonnie alive," Bess said.

Huffman planned on spending the time in Cape Girardeau with her cousins, but they weren't at home, so she began the trek back home.

Around midnight, two people spotted her car rattling along Highway 25 at about 30 miles per hour. An hour and a half later, a driver saw Huffman's vehicle parked in the middle of Route N, and Huffman was nowhere in sight.

Bobby Thiele, her half-brother, and a friend were walking into Delta the following morning and saw Huffman's car.

At first, Thiele assumed the old beast had clunked out on her. But the keys were still in the ignition.

Thiele moved the car to a safer spot at the edge of the road, and as he did so, found a Gene Autry cap gun on the pavement near the car.

Authorities later theorized that the toy gun may have been used to threaten Huffman into getting into a strange vehicle.

In 1975, highway patrol documents showed that most of the physical evidence in the case, including Huffman's clothing and the toy pistol, were destroyed, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported four years ago.

The location of Huffman's vehicle was strange enough that investigators, acting on the missing persons report filed by Huffman's mother, suspected foul play but didn't become certain until the body was recovered the night of July 5, 1954.

Only Huffman's Delta High School ring, inscribed with 1950, the year she'd graduated valedictorian of her class, and her initials, B.L.H., let authorities know that was the woman they'd been searching for.

The sweltering heat had badly decomposed the body. Though sexual assault was suspected, the autopsy results were inconclusive because of the decomposition.

Huffman's checkered shirt was torn, and her underwear, purse, white beaded necklace, watch and shell-rimmed glasses were missing.

The serial number of the watch is known and could provide a link to Huffman's killer if it were ever located, even after so much time has passed, Friedrich said.

Her neck had been broken at the third cervical vertebra, and her jaw had been dislocated.

Hundreds of tips poured in to investigators. Two grand juries examined the evidence in the case, and police conducted dozens of polygraph tests.

Percy Little, former Cape Girardeau police chief, who then investigated the case for the Missouri State Highway Patrol, called the case the most baffling he'd ever faced.

False confession

In 1956, Scott County authorities thought they'd solved the case when they obtained a partial confession from a Chaffee man who claimed to have known Huffman for several years.

"Bonnie was a fine good-looking girl, and I always wanted to go out with her, but I was afraid because she wasn't in my class," the man said in a statement taken by the Scott County Sheriff's Department.

The man claimed to have seen Huffman's car that night on Route N and bumped it several times from behind with his own vehicle, trying to scare her.

He finally forced her to pull over and made her get in his car, the statement said.

He began driving toward town because he wanted people to see them dancing together at the dance hall, but Huffman got scared and leapt from the moving vehicle.

After an hour of searching for her, he said he gave up and went home.

Scott County investigators issued an arrest warrant for first-degree murder for the man based on his statement, but after talking to the suspect, the highway patrol investigators handling the case dismissed the charges.

Police reports said he was of "such mentality that he would respond to a suggestion" and that the confession was "made entirely in response to suggestions rather than being volunteered on his own."

Cape Girardeau County Prosecuting Attorney Morley Swingle said the warrant would not have been valid anyway because an element of the crime would have had to occur in Scott County for them to make an arrest.

A second witness corroborated the man's statement, saying he drove Route N that night and saw the man intentionally bump Huffman's car, but that man was deemed mentally unsound after also describing seeing a submarine rise out of the river, according to police reports.

The arrest, though later unfounded, was the only one made in the 54-year-old homicide.

"If the opportunity ever comes along, we'll get it done," Friedrich said of the case, and wishes he could devote more time to it.

Swingle said the case has always been of interest to him because his father, the late Morley G. Swingle, was one of the original highway patrol investigators.

"I'd love it if it would get solved, but time is critical," Swingle said.

As more potential witnesses and suspects die with the passage of time, chances of solving the case may slip further away, Swingle said.

Ross said she knows there's a strong chance Huffman's killer may be dead but that deep down she doesn't believe that's true.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.