Southeast Missourian boys basketball player of the year: Genes, hard work combined to help Otto Porter excel

Otto Porter Jr. was born a basketball player. He wasn't destined to become one or sure to want to be one. But if anybody can be born anything, Otto Porter Jr. was born a basketball player.

Otto Porter Jr. was born a basketball player.

He wasn't destined to become one or sure to want to be one. But if anybody can be born anything, Otto Porter Jr. was born a basketball player.

He was born to two basketball players from two basketball families from a community defined by its success on the basketball court. So it is impossible to understand Otto Porter, basketball player, without understanding where he comes from.

"I always gave him a ball everywhere we went," his mother said. "A ball was always in his hands."

His story and the story of his family and his school are intertwined so thoroughly that trying to separate them only results in tighter knots and more tangles in the thread that holds them all together.

The story, as it's most often told, goes something like this: Otto Porter's dad, who has the same name, was exceedingly good at basketball. He is a legend and was a member of the first state championship team at Scott County Central High School, which now has won a state-record 15 of them.

The last three titles were won by the younger Otto Porter, who was guided by his father and who, at 6 foot 9, shouldn't be able to shoot as well as he does, shouldn't be able to move like he does and shouldn't be able to make the game look as easy as he does.

But he does all those things anyway, and he became a top college recruit despite living in the tiny town of Morley, Mo., and choosing to play with his basketball-crazed family -- often at his grandma's house, where basketball ruled -- and his high school teammates instead of an AAU team with other top college recruits during the summer.

The ending of his high school story recently was written when Porter signed to play at Georgetown.

Oh, and you can call him Bubba. Everybody does.

This is all true, but it's just part of the story. The problem is even if you could know it all, if you could fill in the gaps and gather all the smallest details about this basketball player who finished his career with 2,482 points scored and is the Southeast Missourian player of the year for a second consecutive season, you only would begin to know the person.

Hard to know

Getting to know Bubba is like guarding him -- a tough, if not impossible, assignment.

He doesn't say a whole lot even among his best friends.

"For real, he really is like that," said Bobby Hatchett, Bubba's cousin, longtime teammate and friend. "He's not going to say too much unless you're like me or some guys on the team that he's tight with. That's what you're going to get out of him every day, all day. He's not going to just talk your ear off about nonsense.

"It's hard because he don't talk a lot unless it's when we talk, but we just be joking half the time. But on a serious note, he's not going to say too much."

Hatchett, who just completed his freshman year at Midland College in Texas where he played for the National Junior College Athletic Association national championship this season, said even people from home call him for news on Porter.

"They call me and they may check up on me and ask me how I'm doing, but they also talk about Bubba," Hatchett said with amusement. "I have to give people the whole inside scoop on him, but I like it though because he deserves it. It'd be bad if it was someone I didn't get along with, but he's cool and he deserves it, so I just have to give everybody the 411 on him because they can't get no information out of him."

Porter isn't so much secretive or shy as he is laid back and unfazed by the onslaught of questions he got about his future from pretty much every direction during his senior season.

In short, by all accounts he's like his dad, who is like pretty much all of the Porters. Even the plaque honoring his dad in the lobby of Ronnie Cookson Gymnasium lauds him for "displaying a calm, mature, sportsmanlike attitude on the court" during his high school career.

"My dad's the same," Porter's first cousin and classmate Calvin Porter Jr. said, adding that's pretty much how all of his Porter family members are, himself included.

The Porter name is sprinkled throughout the SCC and state records books. There is Otto Porter Sr., who was supplanted by his son on the school's all-time leading scorer. (The elder's record 1,733 rebounds will not be touched, perhaps ever.)

You'll also find Jerry Porter and Melvin Porter -- both uncles -- listed time and again, and others not on the all-time lists have contributed on state title teams.

"I guess it's a name that we've been given that we need to live up to, I guess you could say," said Calvin Porter Jr., one of three Porters to start on this season's championship team. "We try to live up to it anyway, and we kind of do it in our own ways."

Bubba wound up 32 points shy of the school's all-time scoring record, which is held by Marcus Timmons. The Timmons name also appears time and again in SCC's history. The record book says Elnora Timmons was named all-state in 1985. That's Porter's mom. Marcus is her baby brother.

"She won a championship, too," Porter said, pointing out his mom's state title resume. "I never knew until I got older that my mom used to play ball. I knew my dad played ball, but not really my mom. But her and her sisters played. They was pretty good at it.

"She always played one-on-one when I was little and, you know, she's still kind of got it."

It was his mom who put a basketball in his hands.

"Whenever he started walking, I gave him a basketball," Elnora Porter said. "I bought one before he started walking anyway. I was like my baby's going to play ball like me."

Grandma's house

When he got older, the ball often was in his hands at his grandmother's house.

"Every time we went over there we always picked up a game," Porter said. "When it rained, we still played through the rain. It cooled us off a lot."

Johnnie Mae Porter, who died in 2008, is spoken about with reverence by her grandchildren. Sure, her house was a gathering place for her basketball-inclined grandkids -- from Otto and Calvin to Dominque and Jaylen to Michael and Corey and anyone else who wanted to hone their basketball skills, but that's hardly all they learned there.

"She took care of us -- fed us whenever need be," Calvin Porter Jr. said. "We could stay over there any time and she was a very, very wise woman. I mean, some of the stuff she'd tell us about and stuff like that, just lessons, life lessons. If you heard what she had to say, I can say you'd be blown away because we all still remember that stuff. Like she read the Bible and stuff like that and she told us be honest, be faithful and stuff like that."

She was the type of grandma who, when her grandsons' rock throwing resulted in the back window of her car being broken, said not to worry about it. She didn't drive it anyway.

"That's why I loved my grandma," Calvin Porter Jr. said. "She was really, really, really cool. She taught me a lot of stuff."

She also oversaw the action on the court if needed.

"They were just real competitive out there," Otto Porter said. "You might have got little scratches and bruises and stuff like that, but that's what grandma was there for."

Somewhere during this time, Bubba fell in love with the game of basketball.

"We all wanted to -- not because our family members did it and not because our mom and dad played -- we just liked to play it, loved it," he said.

"It means a lot," Bubba said when asked what the sport means to his family. "We found something that we love to do and we can do it all day. It's something that we just like to do, love to do and be good at it -- what you love. Not a lot of people can do something that they love to do all the time. I think it's just a great thing for Porter and Timmons families to have."

And it's something different generations of the family continue to share.

"He does a lot of playing with the old guys here and Scott Central, too," SCC coach Kenyon Wright said. "He's done a lot of that, playing with his dad and Jerry Porter and all these guys that are on the wall here. All of them come in on Wednesdays and Sundays and play, and I know he got in a lot of playing time with those guys also."

Porter admits that surpassing the records and accomplishments of his father and other family members is something he thought about and aimed for.

"I just want to be the best at what I do," he said. "That's why I work so hard. I just try to do my best. My grandma always told me, 'Whatever you do, just try to do your best at what you do.' I think that kind of helped me in life in general and playing basketball."

Attracting attention

Bubba lived in Cape Girardeau until his sixth-grade year, when he and his family moved to Morley and he started to attend SCC.

"Whenever I lived in Cape, my dad used to go to the Osage and just work out," he said. "He told me how to dribble and stuff. Like whenever he'd go lift weights, I'd just be doing that the whole entire time while he was in the weight room.

"I'd just be out there for about an hour just dribbling left handed down and back while the old people played in the court. I was just on the sideline dribbling and dribbling and dribbling."

He did this under direction from his father but didn't need to be forced.

"If you want to be good, you've got to learn how to dribble and stuff," Bubba said, echoing his father. "I wanted to be good, so I did a lot of dribbling."

Even before he moved away from Cape, he began to play on an SCC-based team coached by Larry Moseley, Hatchett's grandfather.

"Everybody kind of knew that we was going to be another group that was going to be good when we were little because there was a lot of people watching us play when we was young," Bubba said. "We always had a full house when we was little whenever we played Charleston or Cape or anybody like that. There'd be a lot of people show up for them games, too."

Hatchett and Bubba spent many days playing one-on-one under Otto Porter Sr.'s supervision. He passed on his distaste for losing and then he taught them how to win.

"That's what made us good because at the time we didn't know," Hatchett said. "He didn't just tell us, 'Yeah, if you just kill each other, you're going to make each other good.' He kind of just put it in us, like losing's not good. You can always have good sportsmanship even though you win or you lose, but losing is just not good."

Bubba rarely was on the losing side at SCC. He finished his career with 115 wins -- many of them by wide margins -- and nine losses, but he still managed to develop a healthy dislike for failure.

"It kills him inside just like it kills me," Hatchett said. "Me, I can kind of see it on his face when we do lose. It hurts him. Even when he miss certain shots he should make or he miss rebounds or he just do something wrong, you can tell it hurt him because he's a winner. That's how his dad is, like bad."

"My dad used to tell me and Bobby the same thing," Porter said. "He would bring him over to my house and sit down and talk about all this stuff for whenever we get in high school.

"He was just saying there's going to be a day when you have to step up and carry the team."

Porter said he could remember taking over that role with Hatchett as early as the sixth grade. The two played on the same team despite Hatchett being a year older.

"I was still the point guard playing up with Bobby," Bubba said. "We both were point guards. Everybody was around the same height and everybody played everywhere. We didn't have a center or anything like that. We just all ran and played."

Porter was 5-10 or so by the time he reached junior high, but his body and game both would grow exponentially over the next few years.

"When his seventh-grade year came on, that's when people knew," Hatchett said. "That's when he kind of changed from kind of just a random guy to, oh, that's Otto Porter Jr. You know what I mean?"

Separating himself

It was around that time that Elnora Porter could tell Bubba was going to be part of a basketball renaissance at SCC.

She watched as he joined his older cousins Drew Thomas, the son on her sister Mary and a future all-state guard for SCC, and Michael and Corey Porter, who went on to star at Sikeston High School, among others to win a national tournament in St. Louis.

"That's when I said they're going to be the next generation that's going to bring it to life, and they so did," Elnora Porter said.

"I said, 'Boy, you're going to make history.'"

By the time Elnora told her son this, it had been more than a decade since the Braves had won a state title. Bubba said he didn't even start dreaming of winning a championship until his freshman year, and the only time he heard about the final four was when his mom occasionally talked about it.

It was important to Elnora that Bubba and his teammates return the team to championship form, not just for the school but "for everybody."

"This is history in the making," she said after Bubba signed his letter of intent to play at Georgetown. "This is history because of this school, this ground with all these kids from our area, all our kids. It's very special."

Bubba shot up to 6-2 by the time he reached high school and played in 20 games at the varsity level his freshman year, including all four of the Braves' playoff games as they returned to the final four.

"We wasn't nervous," Bubba said about his first trip to Columbia. "We was just kind of excited. Nobody'd been in so long. We didn't really know what to expect in our first time going up there, so it was exciting."

SCC returned home with a third-place trophy and a new understanding of what it would take to win.

"We just found out that you've got to come ready to play when you're up there," Bubba said. "You've just got to come ready. You've got to be more focused."

A year later Bubba was a 6-7 force inside averaging 16 points and a team-high 11 rebounds a game as the Braves captured state title No. 13 and the first of back-to-back-to-back championships.

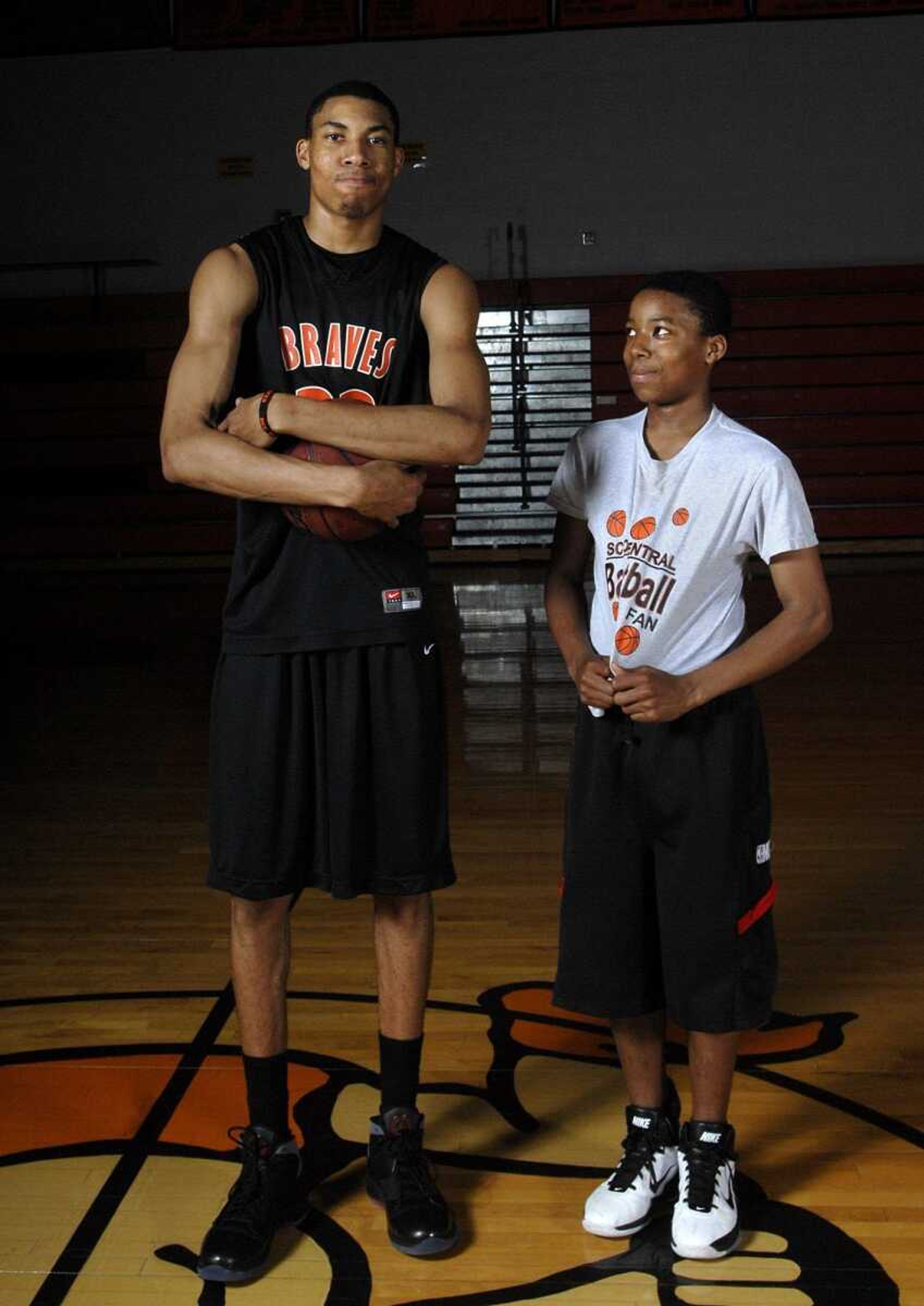

"I remember my sophomore year when we won state, I remember we came back to school the next day the little kids were going crazy," Bubba said.

"That's when it started. All the kids started knowing me. I'm talking about the little kids that walk in the hallways high-fiving and stuff. That's when that started, when I was a sophomore. That was real shocking. I was like, 'How do those little kids know me?'"

SCC grade-schoolers haven't stopped hounding him since.

"Even when we walk over to eat lunch during the day, there are a number of the elementary kids that'll come up to him and he'll high-five them or give them a hug or the whole nine yards because he just enjoys the whole process," SCC superintendent Al McFerren said.

"It's so evident when you come and talk to him. Those kids just love him and he loves them to death."

Growing fame

Somewhere during his junior and senior seasons Bubba's status was elevated from a hometown hero to a regional celebrity.

This is the exchange he inevitably ends up having whenever he ventures out:

Stranger: "Hey! You're Otto Porter."

Bubba: "Yeah, that's me."

Stranger: "You're great!"

Bubba: "Thank you."

"They're like shocked," Bubba said. "It's something that I'm used to now."

He was surrounded by autograph seekers after almost every game the Braves played this season and was asked to sign his own ESPN Rise Magazine cover, programs, shoes and numerous other items -- sometimes even by members of the team he had just helped trounce.

But he also was stopped at the mall in Cape, where one solo trip turned into an extended autograph session signing "shirts, paper, whatever they could find." Then, during an early season visit to a University of Missouri basketball game as a recruit, he walked into Mizzou Arena and suddenly the crowd was chanting his name.

"I was like, 'Wow. How do they know me?" he said.

He told this story weeks before Missouri coach Mike Anderson left for Arkansas and before he chose Georgetown only because teammate Stewart Johnson prodded him to do so, but even he admitted "that was awesome" with a big smile.

He's got more than 4,200 friends on Facebook and acquired more than 1,000 Twitter followers when he briefly made an account earlier this month. And all that attention doesn't account for the calls and texts from college coaches or any media requests for his time.

If life in the spotlight has gotten tiresome, he's never let it show and will not admit it.

"He never told me anything about it," Hatchett said. "We don't really talk about that, but I'm sure he has fun with it. I'm not saying that just because, but I'm sure he do because that's just how he is. I'm sure he's not whining about it like, 'Oh my God, I've got to do this.' Any kid, even when I did it a little bit, it's just fun.

"He ain't doing nothing but making new friends and making people like [him] more, which he's a people person anyway. He's not going to talk a lot, but he's not going to talk down on anybody."

Road ahead

At 6-9 and still more than a month shy of his 18th birthday, the limits are untested for Otto Porter, basketball player, as he heads to Georgetown and the Big East Conference.

"His shooting ability gives him the opportunity to play and be a mismatch in college where he can go and play," Wright said. "That's why I think a lot of colleges have looked at him because he can shoot the ball so well from out there being his size. It's not like there's a lot of 6-9 wing players that can hit that shot out there from the 3-point line, and he can."

Porter averaged 26 points and 12 rebounds during his junior and senior seasons while wowing crowds with everything from emphatic dunks to swished jumper after swished jumper after swished jumper.

"You get a player like that once in a lifetime," Wright said. "I've tried to help him as much as I can and coach him as much as I can and guide him as much as I can with coach [Ronnie] Cookson's help and his dad's help and anybody else I can find help from to give him the opportunities that he has."

Porter is quick to bring up the desire to win a national championship in college.

"I can bet you any kind of money that he's going to try to be the best player in the country," Hatchett said. "That's my goal now. Coach, he told me now it's your turn. You want to be the best player in the country. I know that's his goal because it's my goal. Even if he can't be, that's in his mind. He's going to have his ups and downs there at Georgetown his freshman year, but I know he's going to work hard.

"He's going to try to be the man."

Porter knows he'll need to continue to get stronger to compete in college, though he has no desire to bulk up to the point of losing his touch or his agility. Wright said there are improvements to be made with his left-hand work and with his ballhandling.

All of those challenges will come soon enough, but first he'll graduate as the salutatorian of his class barring any changes in rank.

"We know that he will be able to go out into the world and just represent us to the upmost without any troubles whatsoever," McFerren said. "I would bet my house on it. He's just that special. He's been raised right with the values that we aspire to at our school."

So what Otto Porter has earned, in addition to a college scholarship, is the opportunity to come to define Scott County Central and his family to the nation in the same way they have helped define him for a lifetime.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.