~Acres drained for development are becoming wetlands again under a federal program

Cape Girardeau doctor David Westrich has his own private hunting ground, right in the middle of the industrial area between Cape Girardeau and Scott City.

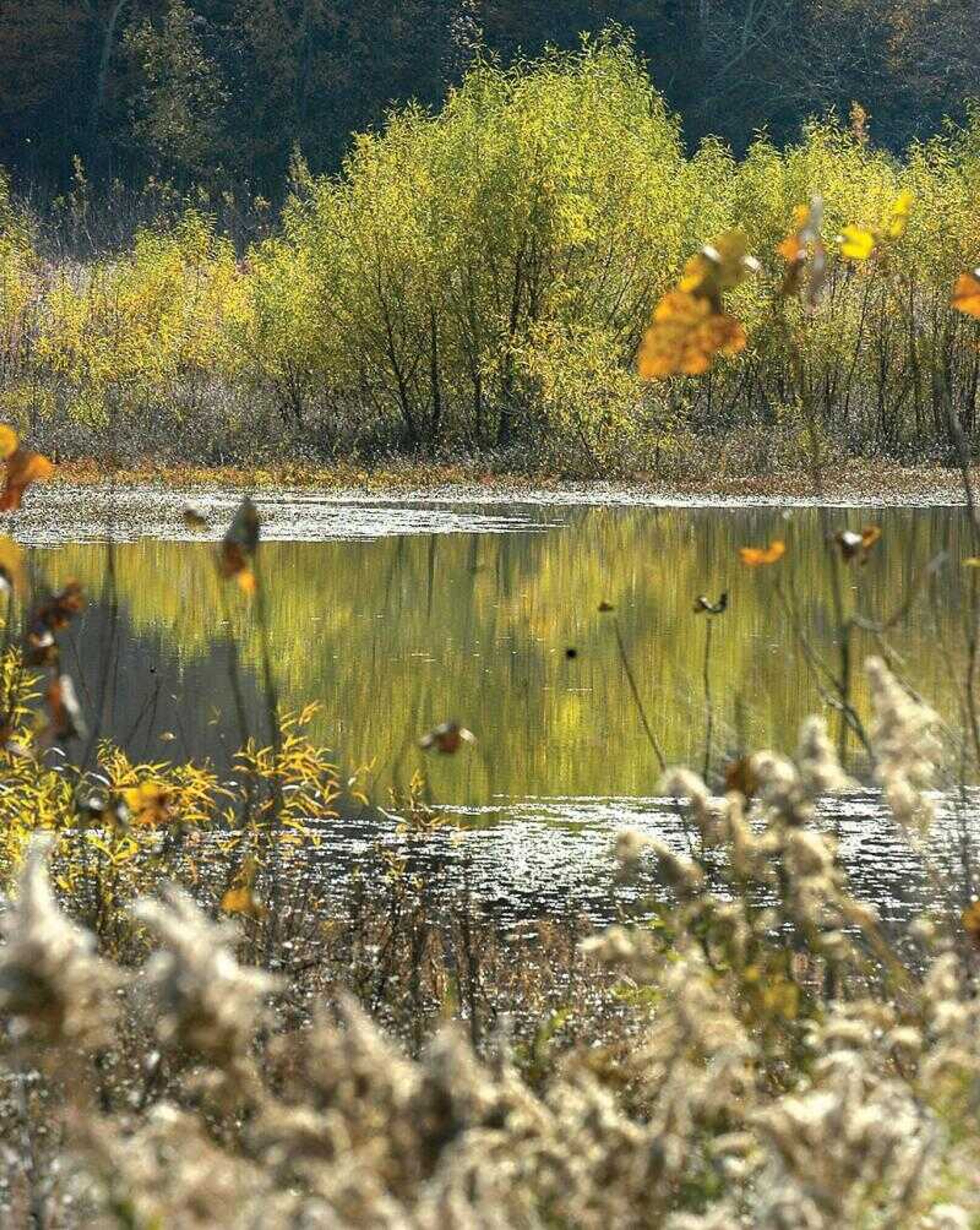

Tucked between the SEMO Port Authority and Interstate 55 are hundreds of acres of wetlands. Long, low pools of water cover much of the ground between man-made levees that retain the liquid, making great habitat for ducks and deer. The hustle of traffic on Interstate 55 a few miles away is unnoticeable. The only things interrupting the serenity of the wetlands are the trucks passing by on their way to the port. Otherwise, these are pristine wetlands, the kind that used to cover much of Southeast Missouri before the area was drained for development.

"I do a fair amount of outdoors things. I like to hunt, I have a lot of friends who like to hunt, my kids like to hunt. It just makes good sense," Westrich said.

Along with another Cape Girardeau doctor, Scott Pringle, Westrich owns 431 acres of wetlands near the port. Next to the doctors' wetlands sits another tract of 103 acres owned by Louis Heisserer, making a near-contiguous area of wetlands between the interstate and the port. They are just a few of the many Southeast Missouri residents who have put their land into the Wetlands Reserve Program -- enough to make the region one of the most fertile areas for wetland restoration in Missouri.

The WRP is administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, giving landowners payments to convert their property into wetland tracts. Most of the property is marginal farm ground, where flooding often destroys crops and cuts into farm profits. For many of those farmers, converting their farming ground into wetlands is not only a conservationist choice, but a smart business move.

Stoddard County farmer Ken Minton has 190 acres in the WRP near Otter Slough that were just put into the program in the last few years. After lands become a part of WRP, they are engineered to re-create the wetland habitat they used to contain -- a long process involving land surveys, cutting channels for water and installation of levees and a water-control system.

The process is long, but for Minton the wait was worth it. WRP has provided him a way to diversify his farming operations.

Now he rents out space on the 190 acres to duck hunters, making a little extra cash from land where water might sometimes ruin crops.

"With the farming economy the way it has been, enough diversification will help you get through the tough times," Minton said.

But economics isn't the only appeal to owning his own wetlands, said Minton. "It's an exciting opportunity to see it go back into something future generations can enjoy, too," he said.

WRP was formed in 1992 with seven pilot states in the program, Missouri being one of them. In 1995, the program came under the jurisdiction of the USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service.

Landowners with ground prone to flooding apply for entry into the WRP, and their land is then studied to see how easily it can be converted back into wetlands. If the land can be converted, the landowners are given fair market value based on a government appraisal. They keep the rights to the land, but the federal government gets an easement on the land for 10 years, 30 years or permanently.

Since its start, WRP has experienced huge growth in Southeast Missouri, said Nancy Ayers. Ayers and her teams of biologists and engineers administer WRP sites and enrollment in a 28-county area, from Franklin County in the north to Pemiscot County in the south, from Mississippi County in the east to Texas County in the west.

"We have more applications than we have money to fund them," Ayers said. The deadline for fiscal year 2007 funding is Dec. 1.

Southeast Missouri has some of the state's largest tracts of wetlands under WRP, making Ayers' office extremely busy.

The area Ayers administers holds 20,217 acres of wetlands in WRP easements out of 116,839 easement acres statewide.Missouri ranks in the top seven states in terms of acreage in the program, and in the top six in contracts enrolled since fiscal year 1999. New Madrid County is one of the top counties in the state with 5,559 acres enrolled in WRP.

One of the primary reasons is Southeast Missouri's ecological history -- the area was once covered largely in wetlands. "The purpose of WRP -- we have to restore what was historically wetlands," Ayers said.

But the process isn't a quick and easy payoff for farmers. Many steps have to be taken to put land into the WRP -- the land is studied for its ability to maintain a wetland, appraised and the owner is made a monetary offer before site construction can begin. When the process is over, farmers in some Southeast Missouri counties can receive up to $2,250 per acre of land, while farmers in the western part of the region receive up to $900 per acre -- prices based on the land's fair market value -- that can be taken in one lump sum or in payments.

After land is put into WRP there can be problems. Ayers said trespassing is common on WRP ground -- people think the lands belong to the government, not private landowners.

And farmers still pay taxes on the land. But for Doug Riddick of Portageville, any negatives that come with participation in the WRP are minor. He owns a 320-acre site in Pemiscot County and used to own a 580-acre site in Bollinger County.

"I like the idea that they give you appraised value and then they come in and build all of the levees and plant trees," said Riddick. "Then you still own the farm. You have to pay taxes, but you still have something."

Minton has seen his ground near Otter Slough complete an ecological circle. He remembers his father clearing huge cypress trees from the land. Only three trees remained, too big to be pushed down, rising above the cropland. The trees are still there, and now the land is being planted with more cypress.

Minton said he asked his father what we would have thought if the government had told him in the 1950s he could get money for converting his land back to swamp. He said his father's answer was "I would have said send them to the nuthouse."

msanders@semissourian.com

335-6611, extension 182

By the numbers

WRP acres by county (as of October 2006):

Scott County: 2,194 acres in 13 contracts

Bollinger County: 2,054 acres in 11 contracts

Perry County: 66 acres in one contract

Stoddard County: 875 acres in 15 contracts

Butler County: 891 acres in 10 contracts

Mississippi County: 984 acres in nine contracts

New Madrid County: 5,559 acres in 18 contracts

Pemiscot County: 3,725 acres in 13 contracts

Dunklin County: 3,869 acres in 14 contracts

Missouri contracts enrolled (FY1996-2006):

671 (second in nation)

Source: USDA

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.