The winter of his content

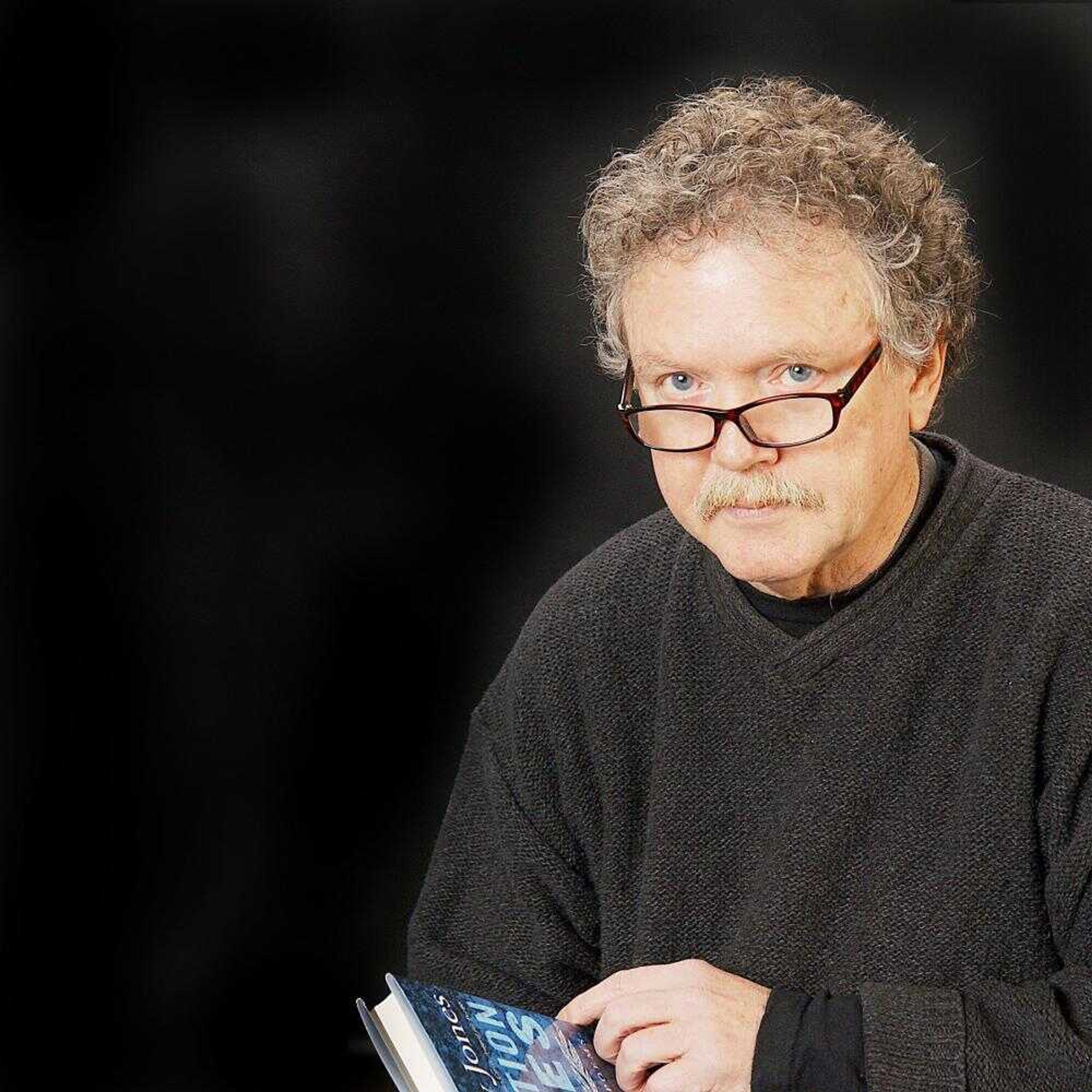

CARBONDALE, Ill. -- Rodney Jones is an everyman's poet. He grew up in rural Alabama, and his poetry commemorates events like his first taste of Coca-Cola and a raccoon that once "skittered" in through his chimney. But from now on this aw-shucks style will come with a major stamp of literary approval. ...

CARBONDALE, Ill. -- Rodney Jones is an everyman's poet. He grew up in rural Alabama, and his poetry commemorates events like his first taste of Coca-Cola and a raccoon that once "skittered" in through his chimney.

But from now on this aw-shucks style will come with a major stamp of literary approval. Earlier this month, Jones, a professor at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, won the Kingsley Tufts Poetry award for his latest collection, titled "Salvation Blues." The award carries with it a purse of $100,000 and is the largest prize available to a midcareer poet.

"It's hard for a girl not to have her head turned by an award like that," he said, laughing.

Since then, his most opulent purchase has been a Fender Telecaster guitar. But he talks about fixing the gutters on his roof and paying college tuition for his 17-year-old son.

These simple needs are representative of the man who grew up on a cotton farm four miles from Falkville, Ala., a town of 400 people.

"It was very much like being a part of another age. Our community still did not have electricity until I was 5 or 6 years old," he said.

"There were no large towns around; it was very backwoodsy. People still felt like pioneers then, I think," he said.

But the isolation had its benefits. Jones played baseball, basketball and football in high school and said at such a small school he felt like a star.

"I was not gifted, but I was obsessed with it," he said of sports. "It was a small enough school that one just needed to have maybe all four limbs, you know. Having that, you felt gifted."

Small-town life had other benefits. Jones didn't have a television set in his home until age 12 and turned to authors like Mark Twain and Charles Dickens when he needed to escape his surroundings.

"I liked to read much more than I liked to work on the farm. ... Reading is your video game. It is your other world," he said.

Jones didn't start seriously writing poetry until he arrived at the University of Alabama. There, he found himself living in a dormitory with a poetic-minded student named Everette Maddox.

Maddox was a bit different (he eventually would die homeless in New Orleans), but at that time he had published poems and quickly put Jones, the country bumpkin, in his place.

"One of the first things he said to me was, 'You're illiterate,' and he was right. I decided I wanted to write something that did not sound like myself. Because I knew the language I had was not good enough," he said.

But through hard work the fledgling poet found his voice. He said he read authors like James Dickey, a Southern poet who wrote about the outdoors in a style then called "country surrealism." Reading people with similar backgrounds helped.

"When I tried to write about what was in my heart, then I failed. But if I tried really hard to write about the country that I knew and the places that I knew, then I found I had some facility," he said.

Finding a voice, he said, is hard. "Of course you have it all along, but it's been polluted by all the things people have told you or suggested to you about how you should be talking."

Those who read him today greatly admire his style.

Robert Wrigley, who teaches at the University of Idaho, sat on the jury that chose Jones for the award.

He "is a poet whose work is intellectually sparkling and at the same time beautifully readable. 'Salvation Blues' includes poems that delight and move and challenge and reward almost any reader you can find," he said.

Helena Bell, a graduate student at SIUC originally from New Orleans, said Jones is also a great teacher. Her first semester on campus she found herself intimidated by her fellow students and unsure of her own work.

But "over the course of the semester I think I ended up writing 12 to 15 poems and actually liking most of them. It was extremely freeing, and he just gave really great feedback," she said.

Bell said that coming from the south herself, she particularly enjoys Jones' celebration of Old Dixie. Her favorite poem of his is titled "Elegy for a Southern Drawl."

All agree there is little affectation in Jones' writing and no in-jokes that only the poet and his elite circle of friends can understand.

Instead, he tries to be accessible, which is not the same as being easy to read.

"I'm against all the games that might be played in a poem like 'guess what's behind my back.' Everything I do in a poem can be seen. It may not be seen easily, it may be some work and I don't believe in dumbing out anything."

Jones is the poet least likely to be found hanging out with other poets.

In one poem called "The Work of Poets," Jones writes as though he's speaking to a sharecropper, Willie Cooper, who he knew from his Falkville days. In the poem Jones is self-consciously trying to explain what a poet does to the illiterate man.

"You planted a long row and followed it. Signed your name X/ for seventy years," he writes. Jones goes on to describe his own writing in the "amnesia of libraries" where "footnotes are doing their effete dance," and asks Willie, "What can I do for you now?"

Jones seems to hope his work can be read by the snob and the common man alike.

"I feel badly for writers who write to push buttons or to please or to fulfill pre-existing templates. I think the great challenge is to try to find out what one really thinks about something, but I am not personally comfortable with making completely inaccessible poetry," he said.

At the same time, Jones wonders about the future of poetry. Awards like the one he received are practically nonexistent. The highest selling collections of his sell about 4,000 copies.

"There are more poets today than ever before and fewer readers," he said.

tgreaney@semissourian.com

335-6611, extension 245

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.