Mountain men relive trading days

ST. ROBERT, Mo. -- Missouri became a state in 1821 and remained the farthest western state until Texas was admitted to the Union in 1845. However, outside of cities on the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, like St. Louis and Jefferson City, much of the state was barely settled. ...

~ Trade Fair attracts traders from all over Missouri

ST. ROBERT, Mo. -- Missouri became a state in 1821 and remained the farthest western state until Texas was admitted to the Union in 1845.

However, outside of cities on the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, like St. Louis and Jefferson City, much of the state was barely settled. In the 1830s, the area of the Ozarks now occupied by Pulaski, Phelps and Laclede counties was part of one large "Crawford County" stretching from Steelville all the way west to what's now the state of Kansas, and all of southwest and south-central Missouri was part of one large "Wayne County" stretching west from the St. Francis River that occupied nearly a quarter of the state's territory.

Few people other than American Indians lived in the Ozarks; those who did were sometimes the descendants of French fur traders who had lived in Missouri for centuries before it became American territory. Others were more recent immigrants from Kentucky, Tennessee and other states on what was then the American frontier.

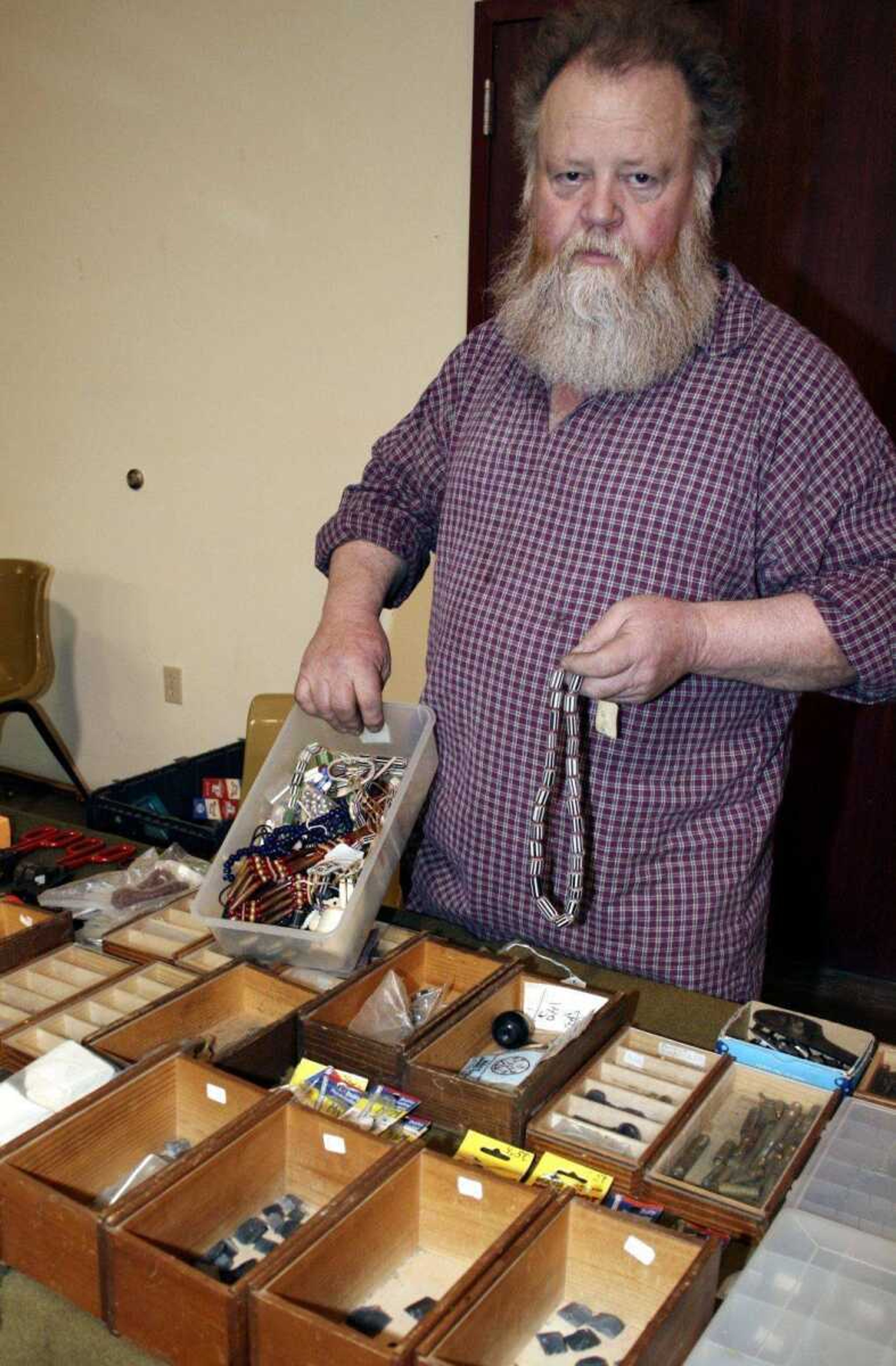

Those days are long gone, but several hundred people whose hobby is re-enacting the lives of the "mountain men" of the early Ozarks gathered recently to buy trade beads, black-powder rifles, powder horns and historic clothing that would have been worn by the beaver trappers, hunters and other early settlers of Missouri.

Held each year at the St. Robert Community Center, the Mountain Man Blackpowder Trade Fair attracts traders from all over Missouri.

Separating men from boys

Among those traders was John Pieron, a Warrensburg machinist who was introduced to the traditional crafts of Ozark "mountain men" three decades ago by his father-in-law.

"He asked me if I'd ever winter-camped, and I said, 'Only in a hotel,'" Pieron said. "Winter camping kind of separates the men from the boys, as far as I'm concerned."

Winter camping, Pieron said, involves sleeping in traditional tents and using the clothing and heating methods that would have been used in the first third of the 19th century.

Fires were made using flint and steel, and survival in the era of canoe travel along rivers could depend on whether a traveler was able to recapture his flint and steel if his canoe overturned.

Mountain men of that era wore large woolen hats with their flint, steel and cloth for burning sewn into the top and important travel documents sewn into the brim, so the floating hat would be more likely to be recovered in case of capsizing.

"Everyone who does this is a little bit of a historian, and we share our knowledge together," Pieron said.

Items sold by Pieron at the trade fair fall into the three main categories carried by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark as they traveled up the Missouri River: trade beads, silver mirrors and silver for trade.

Mirrors were especially important in trading with American Indians, Pieron said.

"Imagine going up to an Indian for whom the only time he's seen himself is a reflection in the water; it's just amazing," Pieron said.

Other items he sells have more practical use in the modern era, including hand-crafted tomahawks made by a vocational technology teacher.

In the early 1800s, tomahawks were useful both as a weapon and as a tool.

"When you take a large carcass, you are not going to put a whole elk on your back and walk off," Pieron said.

Tomahawks were an easy tool to cut a carcass into portions so it could be carried back to a camp in pieces; hunting knives would then be used to dress and prepare the meat for cooking and the hide for tanning.

A skilled toolmaker using traditional methods can craft a tomahawk in about four hours, Pieron said, but they're valuable because few people today have the blacksmith tools of a hammer and anvil needed to produce a tomahawk.

Pieron's own tomahawk collection includes some that are up to 200 years old.

Pieron travels throughout Missouri, Illinois and Kansas to trade fairs, and his local Pulaski County customers are largely drawn from the Kickapoo Trace Muzzleloaders club. That organization owns a camp on 80 acres of land south of Dixon and sponsors an annual Mountain Man Rendezvous in conjunction with Waynesville Old Settlers Day in the city park.

The Kickapoo Trace Muzzleloaders membership includes Daniel Cerda, who retired from the Army in 2003 after seven years stationed at Fort Leonard Wood as a member of an advanced individual training engineer unit.

The skill required to aim and fire a pre-1840 rifle was what attracted Cerda to the mountain man events.

"It was more of a basic shooting as opposed to just pointing and pulling the trigger," Cerda said. "You have to actually think about what you're doing."

Modern automatic and semiautomatic military weapons are designed to pump large amounts of rounds in the general direction of the target, and while accuracy is valuable, it's not essential except for snipers and other specialists. For a rifleman in the 1830s, however, accuracy wasn't just important -- it often meant the difference between life and death.

"You had only one shot, you had to take your time at your shot, so you had to aim steady," Cerda said. "It's more of a challenge going back to the basics and knowing what our forefathers had to go through."

The hobby draws both men and women, with many wives of "mountain men" becoming specialists in period clothing and hand-crafting buckskin leatherwork or clothes made with drawstrings, tight cuffs, feathers and beads.

Traders visiting St. Robert included Erna La Sela of Marshfield, who brought traditional shirts and clothing that would have been worn during the mountain man era.

Clothing sold by La Sela included a "capote" -- a fringed blanket that merged the weaving technology of the European settlers with American Indian ingenuity.

"The fringes would carry water away from the cloth and let it dry," La Sela said. They saw a blanket, knew what needed to be done, cut it up, and made what they needed."

Items like that aren't readily available in central Missouri, Cerda said; trade fairs such as the weekend event are often the only way to obtain historically accurate clothing, weapons and accessories like powder horns without driving to St. Louis or ordering from the Internet.

The trade show also builds camaraderie among people with shared interests.

"You go to one event, you meet people and go to another state and see the same people again," La Sala said.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.