Penalty of Death, Part 1: 15 years ago this week, Russell Bucklew ended the life of Michael Sanders, changed the lives of others forever

If some of life's first memories are somehow sacred -- a mother's tender touch, a playful family pet, a pretty preschool teacher -- then the first recollection in the life of Zach Sanders is more akin to blasphemy. His first memory, from age 4, is neither sweet nor sentimental, nor an event he reflects on with any sense of dewy-eyed affection...

If some of life's first memories are somehow sacred -- a mother's tender touch, a playful family pet, a pretty preschool teacher -- then the first recollection in the life of Zach Sanders is more akin to blasphemy.

His first memory, from age 4, is neither sweet nor sentimental, nor an event he reflects on with any sense of dewy-eyed affection.

The first thing Zach Sanders remembers is watching his father die.

That day -- March 21, 1996 -- comes back to Zach all these years later in hazy hues and garbled sounds, a few out-of-focus mental snapshots and a shudder of the fear he felt.

He remembers. It's there, through the prism of time.

He and his older brother, John Michael, are in the living room.

John Michael is playing Super Nintendo.

The two little girls who had recently moved in with them, Cristin and Charley, are there, too.

Zach's dad and his new friend, Stephanie, the girls' mother, are in the back bedroom.

A knock.

Unaware of what he's letting in, John Michael unlocks the door.

That's when Russell Bucklew steps, uninvited, into their lives.

His eyes. His voice. Quick. Hot.

He's brought two guns with him.

And rage.

Zach has seen the man before, though he doesn't remember the earlier meeting, when the man held a knife to his father's throat.

Now, seemingly from nowhere, Zach's dad appears.

He shoves Zach and the other children down the hall and into the bedroom.

There are shouts. Then shots. Then screams.

Zach's father is down.

Zach's father is bleeding.

At some point, his brother grabs Zach -- "We've got to hide," he says -- and pulls him deep into a closet and into the tight confines of a toybox.

They pull down the lid.

The world goes black.

That's where Zach's memories of that day go black as well.

There is more that happens this day. Much more. The man who sent four bullets tearing through his father's flesh will hurt others.

The man will take Stephanie with him, bound and bruised, where he will do unspeakable things to her throughout a tortuous night that will end with a shootout with police more than a hundred miles away.

While his memory is still spotty, Zach has since come to know exactly what happened that day and those after.

The man will be taken to jail, but the atrocities won't stop there. Somehow, the man will escape and continue his reign of terror for a harrowing two days.

Later, the murder trial, where Zach's big brother, at 7 years old, takes the stand, points at the man and declares that he is the one who stole their dad from them.

The man is sent to prison, sentenced to death.

But in a way, this, too, is only the beginning. It kicks off years of nightmares, nagging questions and a maddening wait for justice.

Not to mention what happened to Stephanie in the end, her life also cut short by gunfire, though that would be at the hands of another man, many years later.

Today, Zach doesn't think about his father's death as often as he used to.

He's made an effort to suppress those memories.

Over the years, Zach has suffered through nights of fitful sleep, bad dreams and occasionally has awakened, crying.

He doesn't dwell on it.

It's not his way.

Today, now 19, he brushes those thoughts aside.

It's in the past, he tells himself.

But when he does allow himself to think about that day, he thinks of it in simple terms.

It was the day Russell Bucklew killed his dad.

---

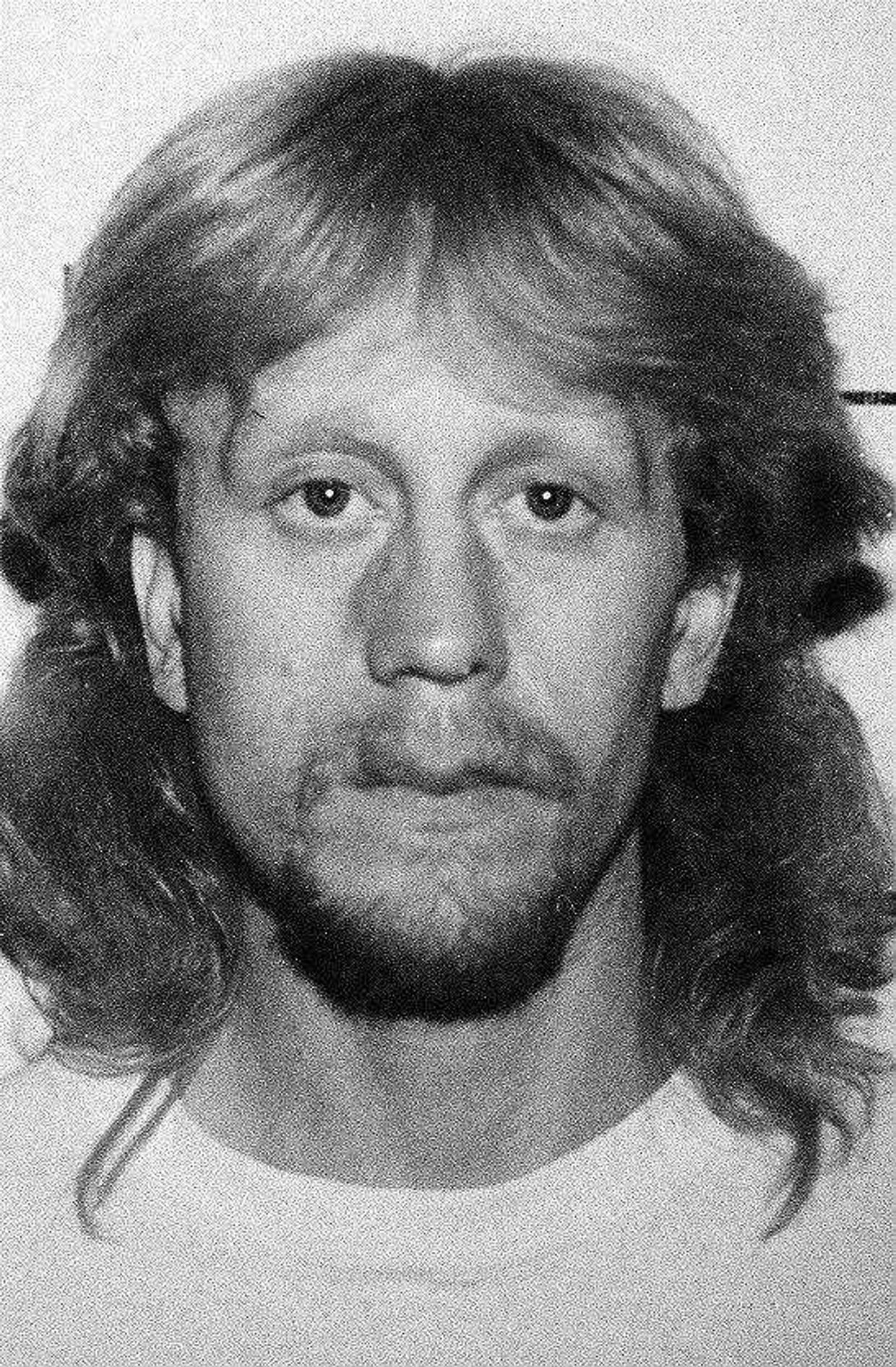

Russell Bucklew's murder of Michael Sanders and the abduction of Stephanie Pruitt have been described in law enforcement circles as among the worst Cape Girardeau County crimes in decades, behind only serial killer Timothy Krajcir or perhaps the 1992 triple murder of the Scheper family.

After 20 years of putting criminals in prison, Cape Girardeau County Prosecuting Attorney Morley Swingle still calls Bucklew "one of the the most evil men I ever prosecuted" and at trial likened him to a "homicidal Energizer bunny."

Sheriff John Jordan was deeply involved in the investigation of the Sanders murder. He also orchestrated the massive manhunt to capture Bucklew when he escaped from the county jail three months later.

During a recent interview, Jordan didn't mince words: He called Bucklew an animal.

"He was a bad character," Jordan said. "He had such a blatant disregard for human life, a blatant disregard for authority. He just doesn't care. He's going to do what he wants to do. He's going to kill Michael in front of his children. He's going to torment Stephanie. He's going to capture her, rape her. It was a very heinous crime."

Both seasoned law enforcement officials have seen many heinous crimes. But nothing quite like this one. Nothing quite like the man who committed it.

Both Jordan and Swingle expressed frustration that Bucklew is still alive, 14 years after a judge sentenced him to die. For much of that time, Bucklew has been housed at the Missouri Department of Corrections' Potosi facility.

There, along with the other 46 other capital punishment offenders, Bucklew has access to television. He is periodically allowed to go outside. Occasionally he is allowed visits from family.

"It's an appropriate punishment," Jordan said of the death penalty. "The only thing that would have been more fitting was if he had been put to death years ago, as far as I'm concerned."

All of the appeals are exhausted. Technically, Bucklew is among the next two or three men who could be put to death.

But it's more complicated than that.

In 2007 Jay Nixon, who was then the state's attorney general, requested an execution date for Bucklew.

That request to the Missouri Supreme Court came four days after a federal appeals court resumed executions in Missouri. With just one exception, the state's executions had been put on hold since 2006 based on concerns about the lethal injection procedure.

One man was put to death in May 2009, after the state developed written protocols that were upheld by a federal judge. But executions were again put on hold while a federal appeals court reviewed those procedures.

In June, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal, essentially clearing the way to resume executions.

Missouri's most recent execution was in February, when Martin Link was put to death for killing and raping an 11-year-old St. Louis girl. That was the state's first execution in nearly two years. It followed the January decision of Jay Nixon, now governor, to commute the sentence of Richard Clay, who was set to die for a 1994 murder-for-hire plot.

The Missouri Supreme Court has set no other execution dates.

But even if it did, the state may not be able to carry them out.

Sodium thiopental is an anesthetic used to put an inmate to sleep before administering lethal drugs.

The only manufacturer of the drug in the U.S. is not currently producing it, which has halted executions across the country due to dwindling supplies.

The Missouri Department of Corrections' supply expired March 1.

For now, Bucklew lives.

---

If only I hadn't unlocked the door.

John Michael Sanders has thought that many times since that day. Maybe a million.

Rationally, he knows it was not his fault. He was only 6.

When someone knocks on a door, you say "come in."

If the door is locked, you unlock it.

That's the way the world works. Isn't it?

"I blamed myself," John Michael said recently, now a young man living in Rolla, Mo., half a state away. "I remember being at my Grandma's kitchen table talking about it. If I hadn't done that, he'd probably still be alive."

The thought has gnawed at him over the years. He replays it in his mind. Picks at it like a scab.

"Don't do it," he tells his younger self.

Again and again, John Michael does it.

Unlocks the door. Lets in his father's killer.

"That was probably the hardest thing to deal with," said John Michael, now 21 and told by everyone that he's the spitting image of his dad.

"I know now it wasn't my fault," he said. "I was a kid. But back then, I thought if I hadn't unlocked the door, he wouldn't have been able to kick it open. But I did."

He considers the scenarios.

One where he doesn't unlock the door.

One where his father lives.

"There could have been a different ending," John Michael says, his voice growing distant.

But that's not how it happened. The past can't be undone.

"There was nothing I could do to prevent it," he said. "He came there with an intent to harm. And he made sure that's what he did."

And unlike his little brother, Zach, John Michael remembers it all.

He remembers Bucklew coming in, kicking the door in after it was unlocked.

He remembers his dad getting his gun. Telling the children to get back in the bedroom.

He remembers his dad going out to confront Bucklew. To protect his family from an intruder.

He remembers sitting on the bed in the room his father had sent him to.

Then he heard the shots.

It was only later that John Michael learned exactly how the bullets ravaged his father's body.

The first shot went into the front part of his dad's chest, piercing a rib and going through a lung before exiting in the middle of his back.

The second shot went in his father's buttocks, presumably as he fell, traveling sideways before it left near his sternum.

The third shot went in near the elbow, traveled through his arm and came out through the meaty portion of his forearm.

The fourth shot went in his right leg near the calf -- right below the knee -- before tearing out through the other side.

All four shots passed entirely through his father's body, leaving no bullets inside.

While Bucklew was handcuffing Stephanie and dragging her out to his car, the girls, Charley and Cristin, had left the bedroom to see what was happening to their mother.

John Michael thinks of his little brother.

"We've got to hide!" he yells at him.

He grabs him and the brothers hide in a toybox. As John pulls the lid down, he hears a car pull away outside.

After a time, John Michael and Zach crawl out of the toybox.

John Michael remembers rushing to his father. He sees him, half in the spare bedroom, half in the hallway. Motionless.

There's so much blood.

That image, his father lying in the hallway, dying, is the one that will haunt John Michael for years, the one that his mind still conjures up from time to time.

John Michael goes to his father.

John Michael is crying.

His father is still alive. He is looking at John Michael.

"Are you all right, Dad? Are you all right?"

His father struggles to talk, to say something to his son.

Perhaps he wants to tell him it will be OK. He will be OK.

Maybe he wants to tell his son he loves him.

In the end, Mike Sanders says nothing.

In the end, he simply fades.

---

It's 10:30 a.m. March 25, 1996.

Four days have passed since Mike Sanders died.

Stephanie Pruitt is back where it happened, a trailer that's tucked away in Hickory Hollow trailer park on County Road 318, just off Route K midway between Cape Girardeau and Gordonville.

Stephanie, all of 21 years old on this day, is wearing jeans and a white T-shirt, her blond hair pulled into a ponytail.

She constantly drags on a cigarette, holding it with shaky fingers.

They're asking her about Bucklew, a man she knew as Rusty.

A dark ring of swelling circles her left eye, more of Rusty's handiwork. On top of everything else.

Officers with the Cape Girardeau-Bollinger County Major Case Squad, the agency that investigates homicides, are looking for answers. They're videotaping the interview, which appears to make Stephanie even more uncomfortable.

She's answering their questions as best she can.

Many are met, however, with exasperated answers.

"I don't know, I don't know," she says. "It just happened so fast."

But she does know. She slows down. Takes a breath. Tries again.

"Mike got to right here," she says, pointing to the door that leads to the hall, which opens into the bedrooms. "I seen Rusty. He had guns."

Bucklew had more than guns. When he came to the mobile home that day to get Stephanie, whom he had dated for about a year until the relationship turned violent, Bucklew came armed for bear.

In addition to the .40-caliber semiautomatic handgun and the .22-caliber revolver, Bucklew was equipped for a mission of madness. He brought extra ammunition, a holster for each of the guns that were strapped to his body, two knives, two sets of handcuffs, a pair of rubber gloves and a roll of silver duct tape.

He brought those things into the Sanders home that day, though Stephanie wouldn't know it until later when he used some of them on her.

The kids had been playing in the living room, while she and Mike talked in the back bedroom. A knock at the door. Stephanie heard John Michael say that there was someone here.

Mike and Stephanie didn't know that John Michael was unlocking the door as they sat there. They had made sure it was locked, fearful that Rusty would come to call.

So they got up, walked to the window in the kitchen and looked outside.

"Oh my God, Stephanie," Mike said. "It's Rusty. Get the kids to the back bedroom."

Mike looked at his new girlfriend, the one he was trying to protect from this madman. The one he had heard about.

Stephanie's father had lent her a shotgun. Just in case. Mike didn't even really know how to use it. Had accidentally fired it in the backyard the week before when he tried to unload it.

Mike told Stephanie to get the gun.

Then he told her to stay back with the children.

Mike, armed with the shotgun, went out to face his executioner.

---

It's Stephanie's worst-case scenario: Rusty. Here. With guns.

Rusty sees that Mike has a shotgun, which infuriates him.

"I'll kill you, you son of a bitch!" Rusty yells.

He opens fire on Mike, screaming words that makes no sense in light of what he's doing.

"Get down! Get down! Get down!"

Mike, mortally wounded, answers in the only way he knows how: "I'm cool, man. I'm down."

Stephanie sees that Mike is trying to crawl.

The girls come out of the back room. In tears.

Stephanie reaches for them. But Rusty's eyes are on her.

He gives her the same orders he's given Mike, telling her to get down, on her knees.

The girls are following the whole time, terrified, crying for their mother.

Stephanie doesn't understand. Or ignores the command.

Bucklew will not be ignored.

He takes the same gun he had just used on Mike Sanders and strikes Stephanie with it, the thick metal landing squarely on the orbital bone of her left eye.

Stephanie's world swims out of focus.

Without wanting to, she follows Rusty's orders and drops, face down, on the kitchen floor.

She isn't quite unconscious. But she can't move, even if she wanted to.

Rusty wastes no time. He's on her in a flash, pulling her arms behind her back.

He tightens handcuffs around her wrists and jerks her to her feet.

He's taking me, she thinks. Oh my God, he's taking me with him.

And then: Oh, Michael. He's killed Michael.

Rusty pulls Stephanie across the kitchen, through the door and out into the yard, past two cars and to a vehicle she doesn't recognize.

She sees the neighbor lady, an older woman, standing on the porch of a nearby mobile home, staring on in horror. They don't know it, but the lady has already taken down a license plate number and is about to call the police.

Rusty doesn't see her. Or pays her no mind.

He has what he's come for. He has what he wants.

Stephanie.

He opens the driver's side door and shoves her into the car and over to the passenger's side.

The girls follow them outside. Rusty yells at them to go back in.

Stephanie doesn't know where they're going. She has no idea that the worst, for her, isn't behind her yet.

As Bucklew starts the car and pulls out of the trailer park, headed for dark, dark places, Stephanie doesn't think she will live to see another sunset.

*** Next: The abduction

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.