Blue and Gray: Cape Girardeau region was divided in its loyalty during Civil War

For Civil War enthusiasts, the ghosts of the conflict are everywhere in Southeast Missouri. They can feel them rising from the early morning mist of the Mississippi River, once filled with Union steamers carrying men, munitions, supplies, the injured, the dying and the dead. ...

For Civil War enthusiasts, the ghosts of the conflict are everywhere in Southeast Missouri.

They can feel them rising from the early morning mist of the Mississippi River, once filled with Union steamers carrying men, munitions, supplies, the injured, the dying and the dead. The long shadows are felt in downtown Cape Girardeau, where Grant once walked in the small river city -- a community that had strong Confederate ties. The ghosts call out from the fertile farm fields and woodlands of the river valleys, places that once saw a constant flow of troops vying for control of the critical city of Cape Girardeau. This was the land of Jackson's own W. L. Jeffers' and his Confederacy-aligned Swamp Rangers, and Capt. Henry Flad, engineer in charge of construction of Cape Girardeau's four fortifications for the Missouri Volunteer Engineer Regiment of the West.

The ghosts are still calling 150 years after Confederate artillery opened fire on the federal Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, S.C., on April 12 and 13, 1861, beginning the bloodiest war in American history. By the time the smoke cleared and the Union was restored more than four years later, the war would claim some 625,000 lives. It would also set free millions held in bondage in a country formed on the principle "All men are created equal."

Missouri, a slave state, a border state, a state divided, would play a critical role in the war. So would Southeast Missouri. About 160,000 Missourians fought on both sides of the conflict. Within weeks of Fort Sumter, war would come to the state and region, and the Show Me State would stand on the front lines of the early action. In 1861, there were more battles fought and more casualties claimed in Missouri than any other state, and Cape Girardeau played a big role, said Scott House, president of the Cape Girardeau Historic Preservation Commission and a Civil War re-enactor.

Today, the Southeast Missourian takes a look at some of the people, places and events in Southeast Missouri that helped shape the Civil War.

Band of brothers

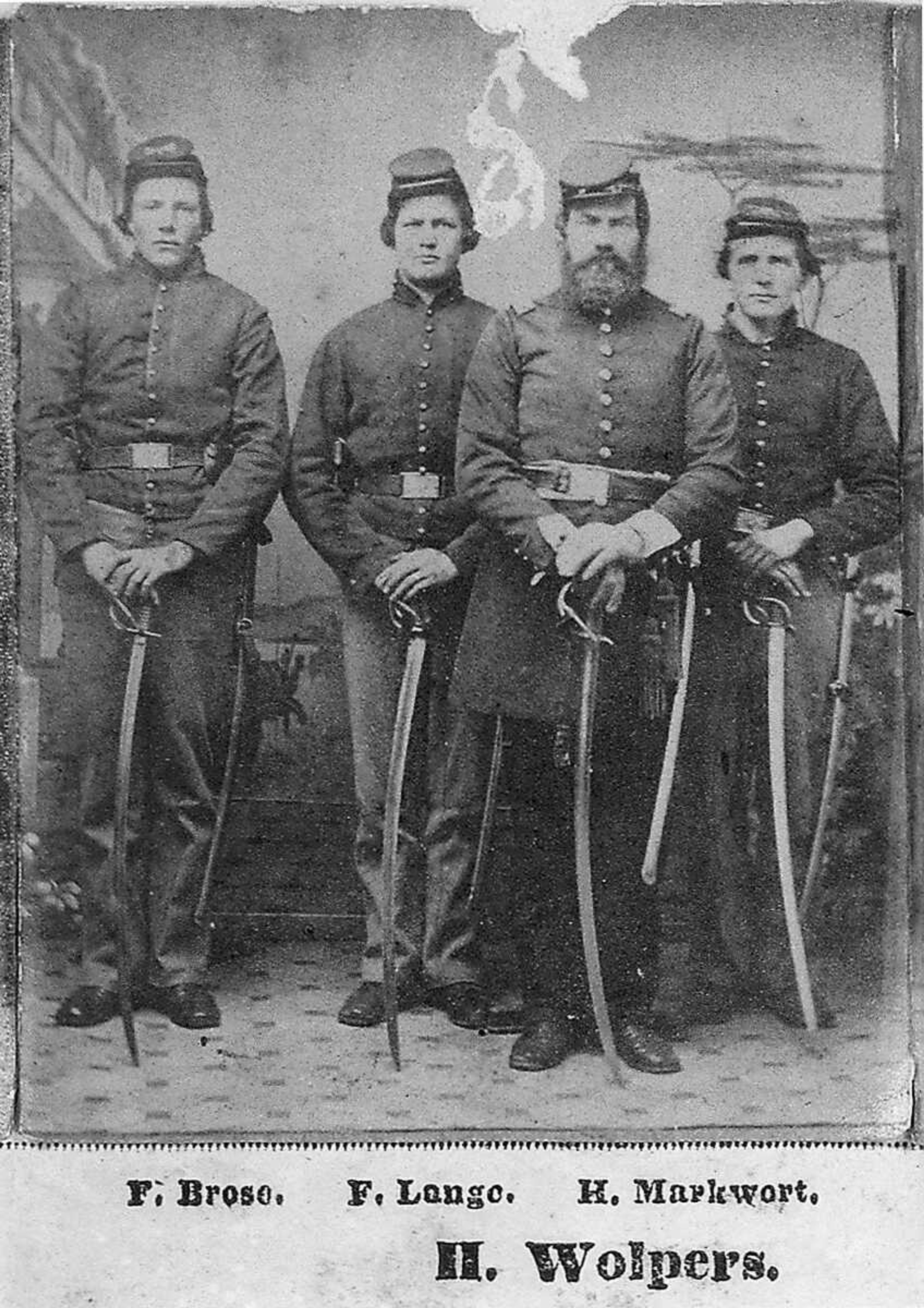

There aren't many places in the region more alive with the Civil War's ghosts than Mike Hahn's farm, on Highway 177 in Egypt Mills. The property has been in Hahn's family for seven generations, purchased by his great-grandfather, Fred Hahn, in 1869, and owned by his great-grandmother's family before that. Mike Hahn's great-grandfather and four of his great-uncles fought for the Union, as so many of Cape Girardeau County's German stock did.

Fred Hahn was 19 when he was mustered in Cape Girardeau's Company G, of the First Regiment of Engineers with the Missouri Volunteers on Sept. 13, 1861. The engineers would build Cape Girardeau's encampments: Fort A, on a bluff above the city on Bellevue Street, Fort B, where Southeast Missouri State University's Academic Hall now stands, Fort C, on Good Hope Street, and Fort D, off Ranney Avenue, which was manned with five cannon, three 32-pounders and two 24-pound smooth-bore guns. Today it is maintained as a city park and historic site.

"There were hundreds and hundreds of spades and shovels," said Frank Nickell, director of the Center for Regional History at Southeast Missouri State University. "In the Civil War, the spade was almost as important as the rifle."

Union forces began arriving in the summer of '61, and they were ordered to take swift control of Cape Girardeau, a city just a few blocks long that counted some 2,600 residents in the 1860 census, many of those with Confederate sympathies. Martial law was imposed and strictly enforced.

"When the Union Army occupied the town, the instructions were that if they saw any Confederate flags flying they would turn the guns on the town. It was a pretty rigid line," Nickell said. Union strength kept Rebel sentiment mostly silent and Confederate attacks, for the most part, at bay.

The exception was the short-lived Battle of Cape Girardeau in April 1863. Gen. John S. Marmaduke invaded the state, with the assistance of Jeffers' Swamp Rangers. Parts of the Marmaduke force, which numbered 5,000 badly armed men, were eventually engaged in the battle. One report notes an intense but futile fight lasting three or four hours that failed to dent the Union line. The Confederates withdrew to Jackson, and Marmaduke moved into Arkansas. The length and intensity of the battle are disputed.

Fred Hahn and his family immigrated to the United States in 1845, escaping the war-torn Prussian states for the presumed peace and prosperity promised in America. As the Civil War broke out, Fred Hahn's mother grew increasingly anxious for her sons. But these hard-working people went when called, bound by loyalty to their new nation and a loathing of slavery and wealthy plantation owners, Civil War experts say.

Fred Hahn served three years, building and rebuilding rail lines, bridges, canals and fortifications into the deep South. His oldest brother died as a result of injuries sustained in the war.

Fred Hahn came home and married his wife, an Egypt Mills Schenimann, also first-generation German-Americans. He rarely ever talked about the war, at least to his family. He lived to be 94 and is buried in a cemetery not far from the family farm he bought from his brother-in-law more than 60 years before.

In Grant's footsteps

The man who would become general-in-chief on the Union Army, and the 18th president of a united United States, arguably began his historic rise in Cape Girardeau. Ulysses S. Grant received his commission as brigadier general Aug. 28 in St. Louis from Gen. John C. Fremont and was ordered to take charge in Cape Girardeau, according to a Daily Republican story in 1911, noting the 50th anniversary of Grant's command of the city and its forces.

The general's stay in Cape Girardeau was brief but productive. He dispatched a command of 13 companies or artillery into the interior, gave orders about the preparation of their rations and instructions as to how they should secure meat as they progressed, impressing on the commander that it "must be done in a legal way," the article in the Cape Girardeau paper said. He ordered up all available wagons, "set a number of fugitive negroes to work on entrenchments and found time to look over the muster rolls of each company in his command." All of which underscored his industrious nature and his attention to detail.

While in Cape Girardeau, Grant stayed at the St. Charles Hotel, described as a quiet and pleasant lodging, a block from the river. He quickly moved on to command Cairo's Fort Defiance before heading off to his destiny.

'O if it be my time to dye'

Charles Schenimann, Mike Hahn's great-uncle on his mother's side, might have survived the war had he only stayed in the Missouri Militia, which saw relatively little action. The young soldier, whose poignant letters from some of the Civil War's bloodiest battlefields betray an unbridled passion for the Union cause, enlisted in Company F of the 29th Missouri Infantry in 1862.

In a letter dated Sept. 18, 1862, from Benton Barracks, Charles writes to his mother, Christine Schenimann, waiting for word at the Egypt Mills farm. In his rough English, he tries to comfort his mother, while defending his decision to fight.

"O Mother doan't greave to much about me onley trust God and he certncy will not forgit us," he writes. "O Mother should I stay at home and sea our govrment lost No indead no so long as I have a arm to strike.

"O if it be my time to dye I will go to my Father in Heaven wher Rebels will never meat us eny more, wee will live in peas and part no more."

Charles was severely wounded in the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou, Miss., near Vicksburg, in late 1862, when three Union divisions under then-Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman were routed.

"Dear Mother, I was wounde on the 29 dc 1862 in the left thy but it is gitten wal fast," Charles wrote. "I was wonded 5 miles from Vix burg in a bayonet charg but we was driven back with a hevy loss."

He spent weeks convalescing in an Army hospital in Paducah, Ky., before eventually rejoining his unit. The wound never really healed.

Charles writes to his brother, Henry, on July 6, 1863, two days after Vicksburg fell to Grant's army. He is overjoyed.

"Never was cheers gave more feeling then when the Stars and Strips was placed on the Forts," he said. He met some Cape Girardeau Confederates. "They was as glad to se me as culd be. Thay are as frindley as ever. Sum of them are glad that thay are taken and sum ses that thay will fight us as long as thay live, while others ses thay will never take arms agane if we will let them go home."

His last letter home to his mother, less than a month later, is short and fatigued.

"Dear Mother, I am sorey to in form you that I am sick and I am so week that I can only set up a little at a time but I think that I will git better sume," Charles wrote on Aug. 4 from Jefferson Barracks, Mo. "I can not writ eny more this time my hand is tiared."

He died of disease, according to his military records, a few weeks later on Aug. 22.

mkittle@semissourian.com

388-3627

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.