Star and Stripes newspaper turns 150

BLOOMFIELD, Mo. -- With tattered edges, slightly faded newsprint, unidentifiable smudges and folds still marked with yellow where Scotch tape once bound the edges, the first printing of the Stars and Stripes shows its 150 years as Wednesday marked the birthday of a military newspaper now more than 50,000 editions strong...

BLOOMFIELD, Mo. -- With tattered edges, slightly faded newsprint, unidentifiable smudges and folds still marked with yellow where Scotch tape once bound the edges, the first printing of the Stars and Stripes shows its 150 years as Wednesday marked the birthday of a military newspaper now more than 50,000 editions strong.

Yet, as one of only three known original copies in existence, many marvel at the journey the four-page broadsheet must have taken from its creation in an abandoned Bloomfield, Mo., newspaper office during the first tumultuous year of the Civil War to forgotten debris littering the attic of an Indiana couple's new house and home again to Southeast Missouri.

It is the centerpiece of the Stars and Stripes Museum and Library located on Highway 25, just south of Bloomfield. The community-built endeavor recognizes the part organizers believe the town must have played in the birth of a news source created for American armed forces members serving abroad during times of war. It has provided a link between the homefront and battlefront during every major American conflict in the last century and a half.

"It's our heritage, of which we are very proud," explained James R. Mayo, president-emeritus of the museum. "It belonged to us. ? There's nothing like the Stars and Stripes. It has covered every war, from the War Between the States to the present. It will go on for years and years, as long as our boys are stationed in foreign countries."

Mayo was president of the Stoddard County Historical Society in 1966 when local residents were first offered the opportunity to return a portion of their history to Missouri. Of the other two known copies, one is held by the Library of Congress and one by the University of Michigan.

Almost tossed on a burn pile with other refuse from an empty house, the thin sheet of paper has been professionally restored and cleaned. It is now encased in Mylar and housed under a thick plastic case in the front lobby of the Stars and Stripes Museum, where more than 6,000 visitors a year can view it and nearly every other edition of the paper ever printed.

From its first editors, it carries the message, "The Stars and Stripes. -- Once More waves over a town lost to patriotism and Honor -- The Union spirit of Illinois has planted its seed in the heart of secessiondom and the Glorious old flag floats over Bloomfield, Missouri!"

They continued in their editorial to ask fellow soldiers, some of which had recently participated in looting local homes and businesses, to take a moment to reflect upon their purpose.

"We should all remember that we have not started out to destroy a country, but to save one, -- that we are fighting, neither for fun nor for glory but for 'God and our Rights,'" wrote the editors, former newsmen turned recruits. "We have the forces that are ready and willing, and sufficient to march forward and lay the whole Southern Confederacy in ashes. But that is not our aim-it is peace that We want, and in order to get it we Should not strive to make enemies on our road."

NOV. 9, 1861

In 1861, the town of Bloomfield was the only settlement of any size west of Cape Girardeau in Southeast Missouri, Mayo said recently, seated in the Stars and Stripes library at a table donated by former Striper, the late Andy Rooney, who appeared for years on the TV news show "60 Minutes."

Stacks of current editions of the paper occupy shelves to one side, while bound books containing hundreds of papers from World War I and on are housed to the other side.

Bloomfield was occupied in the early winter by 2,200 members of the Missouri State Guard. They were not Confederate troops, though many would later join those men, Mayo said, but had been organized by state officials to repel the "Northern invaders." The state guard would disband less than two months later.

Newly promoted Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was headquartered in Cairo, Ill., and fearing an attack from the rear, ordered three regiments to converge from different directions on Bloomfield. The town would change hands more than 20 times in the next five years.

Missouri State Guard Commander M. Jeff Thompson, who earned the nickname "Swamp Fox," ordered his men to move south before Union troops arrived.

"Thompson thought seriously about battling one regiment, but when he learned there were three, he retreated to Clarkton," Mayo said.

An Illinois regiment came through seven miles of swamps along the east side of Crowley's Ridge, arriving Nov. 8, a few hours after the 10th Iowa Regiment, which had arrived from Cape Girardeau. A third group, from Ironton, Mo., was turned back before reaching Bloomfield.

"The (Illinois) regiment came here through the swamps along the east side of Crowley's Ridge. They had a rough time coming through the swamps," said Mayo, who has found diary entries written by Illinois' soldiers describing the "awful gloomy road" as covered with black moss four inches deep.

The Illinois group was ordered to camp for the day and night at Bloomfield and, with no battle to fight, leave Saturday, Nov. 9. They would take a less direct route back along the Old Bloomfield to Cape Girardeau road, to avoid the swamp, said Mayo.

Ten members of the group, all former newspaper men from Southern Illinois, found the abandoned office of the Bloomfield Herald and spent the evening hours of Nov. 8 publishing a paper.

Like its modern day counterpart, the news was gathered by recruits, not officers. It offered advice, a preference on the best wagon for navigating swamp land; advertisements, a stable which could board horses on Prairie Street, while Poplar Bluff, Mo., attorney James Dennis offered his services in the 15th Judicial Circuit; and news from the regiments, including compliments for Aleck Smart's 18th Regiment Brass Band.

There was also a touch of humor, as they spoke of the state guard's retreat, saying, "Jeff Thompson's rebels showed a Good pair of heels in their retreat from Bloomfield, if they did not show good Stout hearts."

WWI

Four more editions would be printed by the end of the Civil War and the Stars and Stripes would not go to press again until World War I.

Newspaper man Guy Viskniskki would later convince Gen. John Pershing of the benefits of a publication run by enlisted men for the armed forces. Viskniskki had an uncle in the Illinois regiment at Bloomfield and shared a hometown, Carmi, Ill., with three of the first 10 Stripers.

Communications with superiors in 1918, republished by Viskniskki's granddaughter, Virginia Vassallo, in the book "Unsung Patriot," show freedom of the press continued to play an important role in the Stars and Stripes' development.

Lt. Mark Watson, assistant chief of the Censorship Division of G-2, wrote that advice of the British and French concerning the use of propaganda in the publication should be ignored.

"They are not Americans," he wrote. "They do not understand the vital difference between the American press, which is genuinely free and which is perhaps the strongest single bulwark that American democracy has, and the European press, which is quite different.

"They cannot appreciate the American soldier's insistence that his paper shall print what he thinks he would write if he were running it."

Printing was suspended between World War I and Wold War II, when editions were published in London, Italy, Sicily, France, Germany, Egypt, Algeria, Tunisia and Honolulu, staying close to the front lines, according to the Library of Congress.

The Stars and Stripes has since been published continuously for U.S. forces from the Korean War, Vietnam War and Persian Gulf War to Iraq and Afghanistan, with an estimated 350,000 readers today.

Two members of the Daily American Republic staff were contributors during their service, editor Stan Berry during Vietnam and photographer Paul Davis, following the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines. They served in the Army and Air Force, respectively.

1966

Bloomfield's copy of the first Stars and Stripes was found in 1966, as Sandra Hudson and her 32-year-old husband, Oliver, cleaned the attic of a 100-year-old home they had purchased and were about to move into.

Hudson said recently in a phone interview she does not remember much about the condition of the paper when they found it, but that it was in a packet with several letters exchanged between a family during the Civil War. The letters were donated to a local historical society, which does not have them anymore, she said.

Bloomfield newspaper articles from the time of the find state that Oliver almost burned the first edition paper without looking at it. When he realized its age, he offered it to the Smithsonian for $250.

While the Smithsonian wanted the paper, Mayo said, they did not have the funds. Oliver next contacted a newspaper publisher in Bloomfield, who passed the information along to the Stoddard County Historical Society. After borrowing $50, the group was able to purchase the paper.

MUSEUM

It took several decades to develop the current Stars and Stripes Museum, Mayo said, and it was done with the help of so many people, he was afraid to name them for fear of forgetting someone.

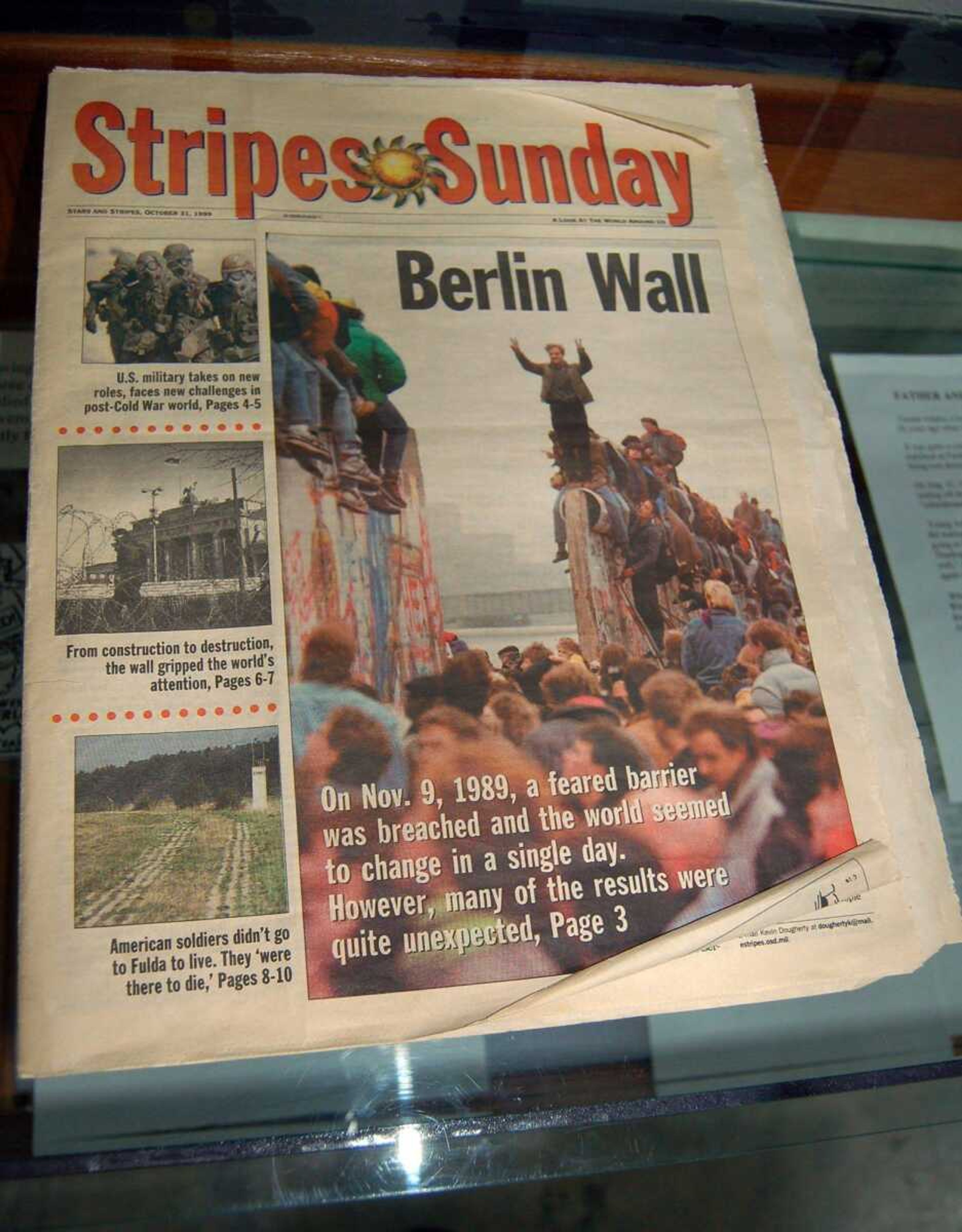

It houses today hundreds of artifacts from every major conflict since the Civil War, as well as what Mayo estimates to be more than 50,000 copies of the Stars and Stripes published throughout the years.

There is the doorknob from the building where the Korean War peace talks were undertaken. It was carried back to the states in a Striper's briefcase.

"Just think of all the history that went through those doors," Mayo says during a tour, between pointing out the World War I marine uniform, the Vietnam field jacket of former Striper and "60 Minutes" correspondent Steve Kroft and other items donated by former Stripers.

The museum also displays photographs taken by the reports at the front lines of World War II and Vietnam, as well many other historical items.

The all-volunteer operation has hosted reunions three times for former and current Stars and Stripes staffers, most recently in September. They continue to build the museum's collection and seek support for the effort.

"What we do here is preserve history," Mayo said.

"I grew up in Bloomfield," said his wife, Sue, also a volunteer, as the couple shut off lights and prepared to lock up for the night recently. "It's my home and I like for people to know about it."

On the web: www.starsandstripesmuseumlibrary. org.

Pertinent address:

17377 Stars and Stripes Way, Bloomfield, MO

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.