Rule will cap public defender caseload

A new rule set to begin Oct. 1 will permit the state's public defender system to defer certain criminal cases in a move that proponents say should give the state's low-income defendants quality legal representation that has been lacking during a decade of swelling caseloads and dwindling resources...

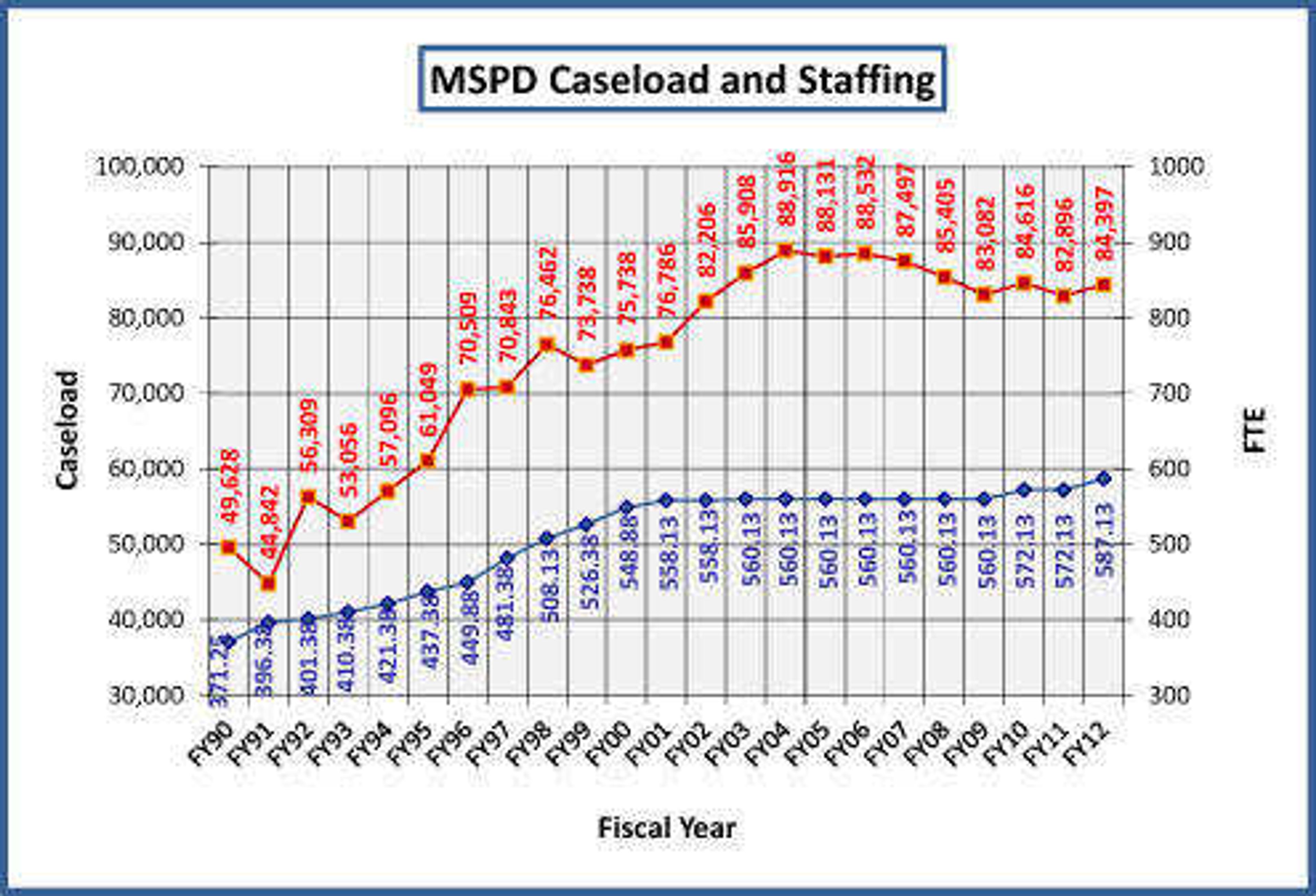

A new rule set to begin Oct. 1 will permit the state's public defender system to defer certain criminal cases in a move that proponents say should give the state's low-income defendants quality legal representation that has been lacking during a decade of swelling caseloads and dwindling resources.

But a number of skeptics, including Cape Girardeau County Prosecuting Attorney Morley Swingle, believe the rule's new formula "greatly exaggerates" the time that is being estimated for the defender caseloads and also suggest that the change is really a thinly veiled attempt to pressure the state for more dollars.

But a July 31 Missouri Supreme Court ruling says the Missouri Public Defender Commission, which oversees the state's 150 public defenders, has the authority to set maximum caseloads if the defender's office asserts that the caseload capacity was exceeded.

"The issue has been going on for a long time," said Cat Kelly, director of the state's public defender system. "The fact is there are too many cases and not enough public defenders to handle them."

Judge Ben Lewis emailed an administrative order to lawyers across Cape Girardeau County on Tuesday that outlines how the rule will be implemented locally. Area judges met with the division director of the public defender's office, District Defender Chris Davis of the Jackson defender's office and Swingle in an attempt to keep case deferrals to a minimum.

Still, local case deferrals seem likely as the 32nd District Defender's office is expected to exceed its caseload capacity under the rule's new formula this month. The 32nd District covers the counties of Perry, Cape Girardeau, Bollinger, Scott and Mississippi.

The public defender system's seven offices around the state have been allotted so many hours based on the district's size, caseload and number of lawyers, Kelly said. In the Jackson-based 32nd District, she said, the cap has been set at 1,316 hours per month. The way it essentially was broken down, she said, was that the district's annual hours worked were divided between each month. Last year, the 32nd District accepted 3,096 cases, or about 79 percent more than would be allowed under the new system, she said. The Jackson office has 11 lawyers.

But not everyone is buying the ways the numbers are being broken down.

Swingle, for example, said Wednesday he believes the hours needed have been exaggerated. For example, 14 hours are set aside for a felony case and five hours for each misdemeanor. Swingle said this jurisdiction has good police agencies that provide detailed reports in every single case that allows lawyers to quickly spot whether they have a chance of winning the case. Ninety-four percent of state convictions are the result of guilty pleas, according to the courts.

Swingle also said that local public defenders have a smaller caseload than prosecutors. According to Missouri court documents, public defenders represent 80 percent of all criminal cases. Swingle also believes the new system is a move to pressure the legislature to give more money to the public defender system, although public defenders make $38,040 to $78,805, more than his assistant prosecutors.

"In an ideal world, the public defender system would get more money," he said. "I'd like to see the prosecutors get more money. But it's not the right time in our state's history to be asking for more money."

Lewis' order goes on to say that the state's high court ruling instructs trial courts to try to reign in their dockets by "triaging cases" so that the most serious cases are given priority. The order instructs the public defender's office to defer representation after the district reaches its monthly cap for offenses such as misdemeanors excluding first-offense driving while intoxicated cases; criminal nonsupport, driving while suspended, driving while revoked, writing bad checks, forgeries and other nonviolent offenses.

Charges are weighted with differing amounts of time, Kelly said, with murders allotted more hours and misdemeanors fewer, she said. The cases that come in after the office has reached its cap will be placed on a waiting list.

Other things the judiciary can do, Kelly said, is for prosecutors to not seek jail time for some offenses. The threat of imprisonment is what kicks in the constitutionally protected right to an attorney.

Another option, she said, is to appoint private-practice lawyers to accept cases for indigent defendants as pro-bono work.

Private attorney Stephen Wilson said he believes that will happen and will likely include asking lawyers who don't specialize in criminal defense to step up.

"It's going to be everybody -- guys who write wills and do trusts, too," Wilson said. "I think that's going to happen."

But Wilson said that once a lawyer is appointed, he or she has an ethical duty to learn what they don't know, no matter the specialty and rise to the task.

Said Wilson: "Aside from the jokes that are told at cocktail parties, I think most lawyers are ethical people."

smoyers@semissourian.com

388-3642

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.