A deadly puzzle: Patience, training help experts gather evidence in homicides

A charred body is found in a burning car. An autopsy later reveals the victim was strangled. A woman is raped and murdered in her home. A quarter-century later, a DNA sample and a palm print taken from the scene help police identify her attacker as a serial killer who eventually confesses to the murders of several other women...

A charred body is found in a burning car. An autopsy later reveals the victim was strangled.

A woman is raped and murdered in her home. A quarter-century later, a DNA sample and a palm print taken from the scene help police identify her attacker as a serial killer who eventually confesses to the murders of several other women.

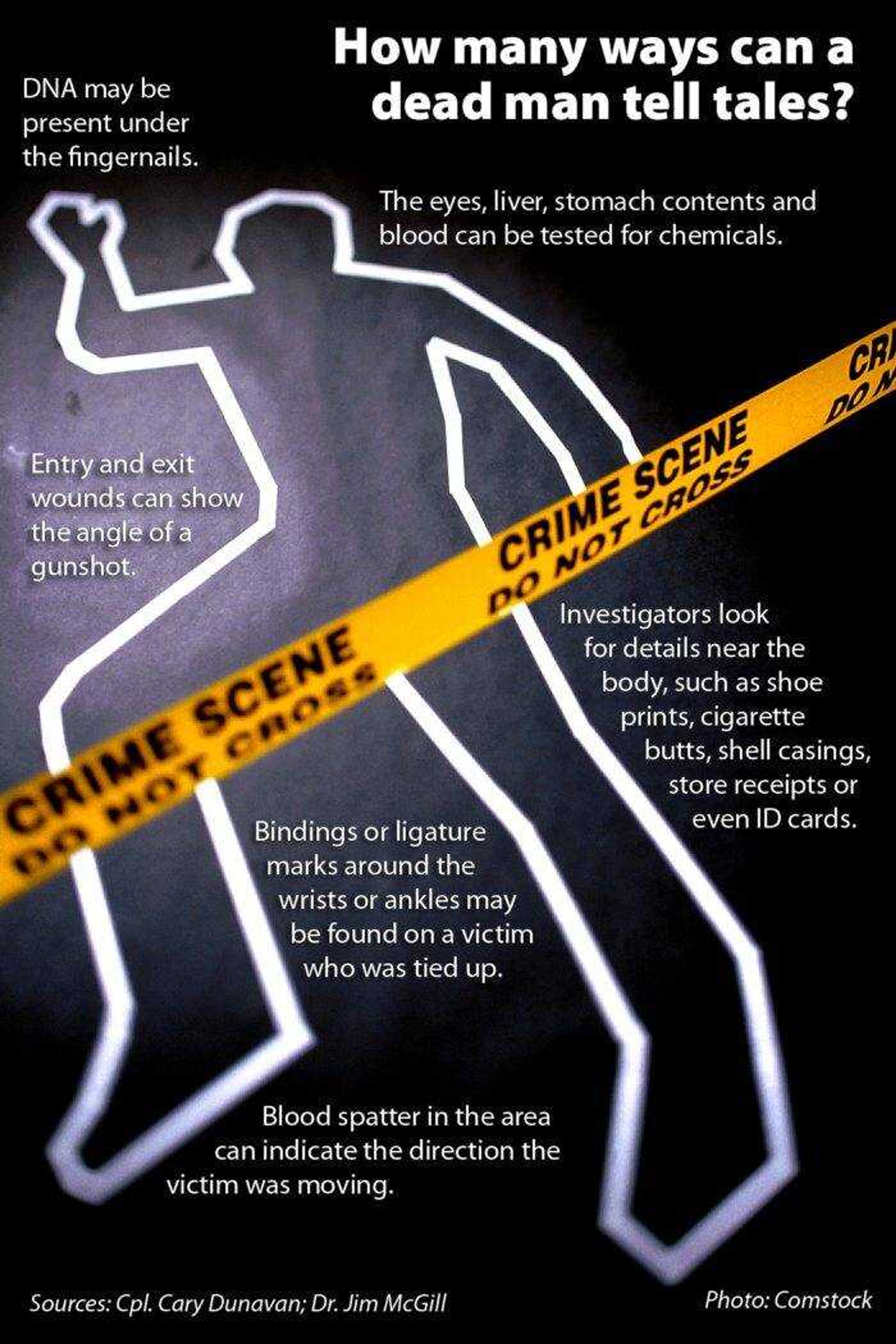

Contrary to popular belief, dead men -- and women -- do tell tales. But learning their stories takes patience, training and an eye for detail, local experts said.

"We're trained to look for something that might look insignificant," said Cpl. Cary Dunavan, evidence supervisor at the Cape Girardeau Police Department.

The smallest detail -- a little gunpowder residue on a victim's clothing, a store receipt in his wallet or a photograph of a neatly made bed -- can help put a killer behind bars.

"What doesn't appear important to us may be important to the prosecutor," Dunavan said. "... Defendant may say, 'Well, there was a struggle in the bedroom. We fought and fought and fought, and I defended myself.'"

If photographs of the crime scene show the room in pristine condition, with no evidence of a struggle, jurors are less likely to believe the defendant's claims, Dunavan said.

At the scene

At a crime scene, Cape Girardeau County Coroner John Clifton said he considers the location of the body.

"One thing I look for is first of all, if a body is found somewhere out, should that person have been there?" he said.

For instance, Clifton said, it's unlikely a banker would be walking through the woods in a three-piece suit.

Clifton also looks for drag marks or other signs the victim died somewhere other than the spot where he was found.

One of those signs is where the blood pools in the body.

"If the blood is pooled somewhere other than the lowest point, we know they didn't die there," Clifton said.

Factors such as internal body temperature or degree of decomposition can help Clifton determine how long ago the person died.

Clifton and Dunavan said they also look for signs the victim put up a fight, such as broken fingernails, tissue under the nails or defensive wounds.

"Each different type of homicide, whether it be gunshot, strangulation, we're looking for different things," Dunavan said.

Toxicology tests on the blood, urine and eye fluid can reveal whether a person died of a drug overdose, Clifton said, while an autopsy can provide further insight into the cause of death.

But with a $70,000 annual budget for autopsies -- which cost about $2,000 apiece -- Clifton has to be selective.

"You can't autopsy every person," he said.

Clifton makes that decision on a case-by-case basis, taking into consideration factors such as the victim's age and the circumstances surrounding the death.

Burned bodies almost always undergo autopsies, Clifton said.

"My policy has been on fires -- with I think only two exceptions -- if a person is in a fire, we'll do an autopsy, because sometimes fires are used to try to cover another crime," he said.

Clifton said he works closely with police officers at crime scenes.

"They make my job a lot easier," he said. "... No one of us is as smart as all of us."

Beyond the body

Details found near a body, such as spattered blood, shoe prints, cigarette butts, receipts or even identification cards can provide additional leads, Dunavan said.

For instance, after checking the timestamps on store receipts, investigators can review surveillance video to tell where the victim might have gone -- and with whom -- in the hours before the murder, he said.

"If it's a shooting, we're going to be looking for casings. We're going to be looking for any slugs we can find," Dunavan said.

The location of cartridge casings can show about where the suspect was standing when the weapon was fired, said Dr. Jim McGill, director of forensic chemistry programs at Southeast Missouri State University.

Bullets may be deformed by the time they pass through a body, but most still have rifling marks -- the pattern of ridges and valleys created when a bullet is fired from a gun, McGill said.

That pattern is unique to each gun, he said.

"If you can find a suspected murder weapon, you can take another bullet under test conditions in the lab" and fire it from the same weapon, then compare the rifling marks to those on a bullet found at the scene, McGill said.

Entry and exit wounds in the body and slugs lodged in walls or other surfaces can give investigators an idea of the path the bullet took after being fired from the gun, Dunavan and McGill said.

Meanwhile, gunshot residue on the victim's body or clothing can indicate the approximate distance between shooter and victim, McGill said.

Too much information

Scientific breakthroughs have given investigators new information to work with, McGill said.

"They say now that if you've got a single cell, that's enough to amplify and get DNA or potentially get a profile," he said. "That's pretty insane to me. That's amazing."

Thanks to that technology, investigators at the Scott County Sheriff's Department are hoping to recover DNA from a bank bag found at the scene the day 19-year-old Cheryl Scherer vanished from the Scott City service station where she was working in 1979.

But DNA can be misleading, especially if it comes from an object several people have handled, McGill said.

"Anybody who's touched that bag could be the donor," he said. "... Could be that profile comes up and leads you down a potential wrong path."

The sheer quantity of potential evidence can create its own problems, Dunavan and McGill said.

"It's a challenge the other way now -- just the overload of information that you could have," McGill said.

In court

During a criminal trial, a defense attorney may seek to discredit evidence. To counter that, investigators must document their findings carefully, Dunavan said.

"Document, document, document. Photographs, photographs, photographs," he said.

Photographs and detailed reports also can help jog officers' memories, Dunavan said.

"We are charged with painting a picture of the scene two years from now, three years from now at the trial," he said.

Physical evidence can disprove or corroborate witnesses' testimony, McGill said.

"Eyewitnesses either way are not particularly reliable," he said. "People forget. People in the heat of the moment misperceive things. People outright lie sometimes. ... So it's good that the physical evidence can either support or refute what they're saying."

To maintain the credibility of that evidence, scientists try to keep their personal opinions out of the lab, McGill said.

"The forensic scientists like we train, we sort of want them to have, like, blinders on or tunnel vision," he said. "We don't want them to think who might be guilty or who might be innocent."

epriddy@semissourian.com

388-3642

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.