Sleuths trace fate of first black male slave freed by Lincoln

MINNEAPOLIS -- Researchers believe they found the grave of a man who could be considered the first black male slave freed by Abraham Lincoln, tracking his final resting place to the cemetery of a former Minnesota psychiatric hospital. William Henry Costley was just 10 months old in 1841 when Lincoln, who still was a young lawyer, won an Illinois Supreme Court case freeing Costley's mother from indentured servitude -- a status historians say would have been akin to enslavement for the woman and child at that time. ...

MINNEAPOLIS -- Researchers believe they found the grave of a man who could be considered the first black male slave freed by Abraham Lincoln, tracking his final resting place to the cemetery of a former Minnesota psychiatric hospital.

William Henry Costley was just 10 months old in 1841 when Lincoln, who still was a young lawyer, won an Illinois Supreme Court case freeing Costley's mother from indentured servitude -- a status historians say would have been akin to enslavement for the woman and child at that time. That was 22 years before Lincoln, as president, issued the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring slaves in rebel states not under Union control free.

Nance Legins-Costley and her son William were from Pekin, Illinois, which is what drew the interest of a historian, Carl Adams. Adams, who lives in Stuttgart, Germany, spent years researching her and her children's lives. Last year he published "Nance: Trials of the First Slave Freed by Abraham Lincoln -- A True Story of Nance Legins-Costley."

In his book, Adams writes after winning her lengthy legal battle for freedom, Legins-Costley, who had been born to slaves and sold twice before Lincoln took up her cause, lived to an old age in Pekin. Military records helped Adams retrace her son's steps, but finding his gravesite required the help of a curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Illinois, and a historical researcher in Minnesota.

"We are 99.9 percent certain that this is William H. Costley," Adams said of the gravesite.

William Costley enlisted as a private in the 29th Regiment of U.S. Colored Troops from Illinois in 1864, three years after the Civil War started.

Costley was wounded during the war, and after Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered in April 1865, Costley's regiment was dispatched to Galveston, Texas. Adams said he may have seen Gen. Gordon Granger's June 19, 1865, declaration there that the state's 250,000 slaves were free. That date now is celebrated as the Juneteenth holiday

In 1870, an all-white jury acquitted Costley of murder in the fatal shooting of a man considered disreputable in the community. Costley's defense was he killed him while protecting a woman.

Costley moved to Iowa and later to Minnesota, where his health declined. A war wound, a head injury he suffered as a teenager and a case of sunstroke in 1887 left him an invalid. He died in Minnesota in 1888, Adams said.

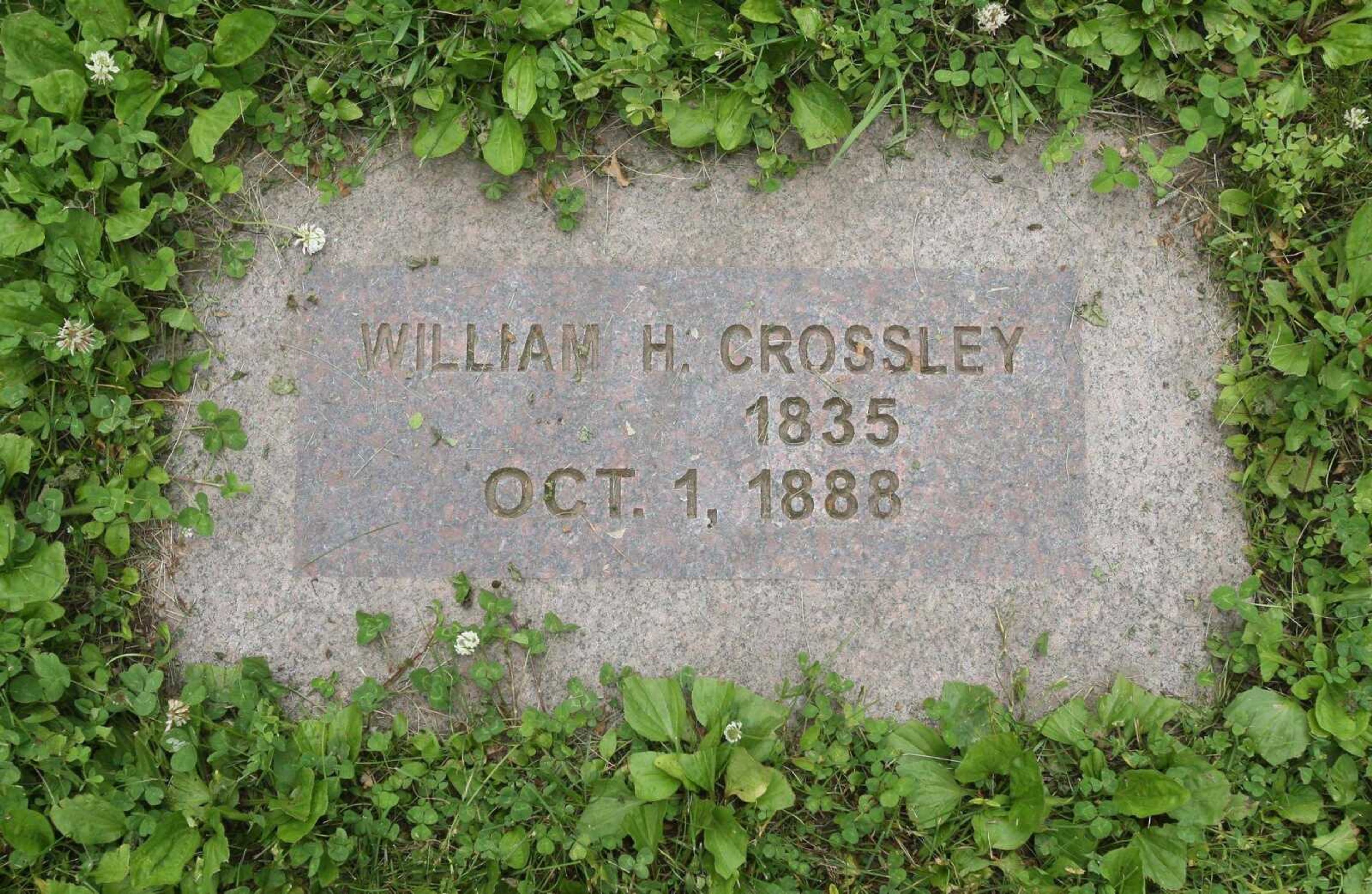

Adams said Costley's pension records show he had been sent to an insane asylum in Rochester, but he couldn't determine where he had been buried, so he enlisted the help of Rich Arpi, a staffer with the Ramsey County Historical Society who also does independent research. Arpi found the Rochester State Hospital's records for a black patient named "William H. Crossley," whose grave was marked by a number at the institution's cemetery in what's now a city park until it was replaced recently by a "Crossley" headstone.

Besides spellings that varied even within the pension and hospital records, there were other discrepancies Adams needed to clear up. The dates of death were slightly different -- Oct. 1 in the hospital records, Oct. 2 in the pension records. But the birth years were five years off. The researchers eventually concluded it had to be Costley's grave. Adams said Costley was illiterate, and may have been incoherent when admitted, so the spelling apparently got jumbled along the way.

"I think it is so likely that it's nearly a sure thing," said James Cornelius, curator of the Lincoln Collection at the Lincoln Library and Museum, who consulted with Adams.

Cornelius said Adams has done a remarkable job of pulling together the history of Costley and his family and resolving the discrepancies to find his grave, given "vanishingly few records" exist on most people who lived on the margins of society because they were slaves, poor or illiterate, as Costley was.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.