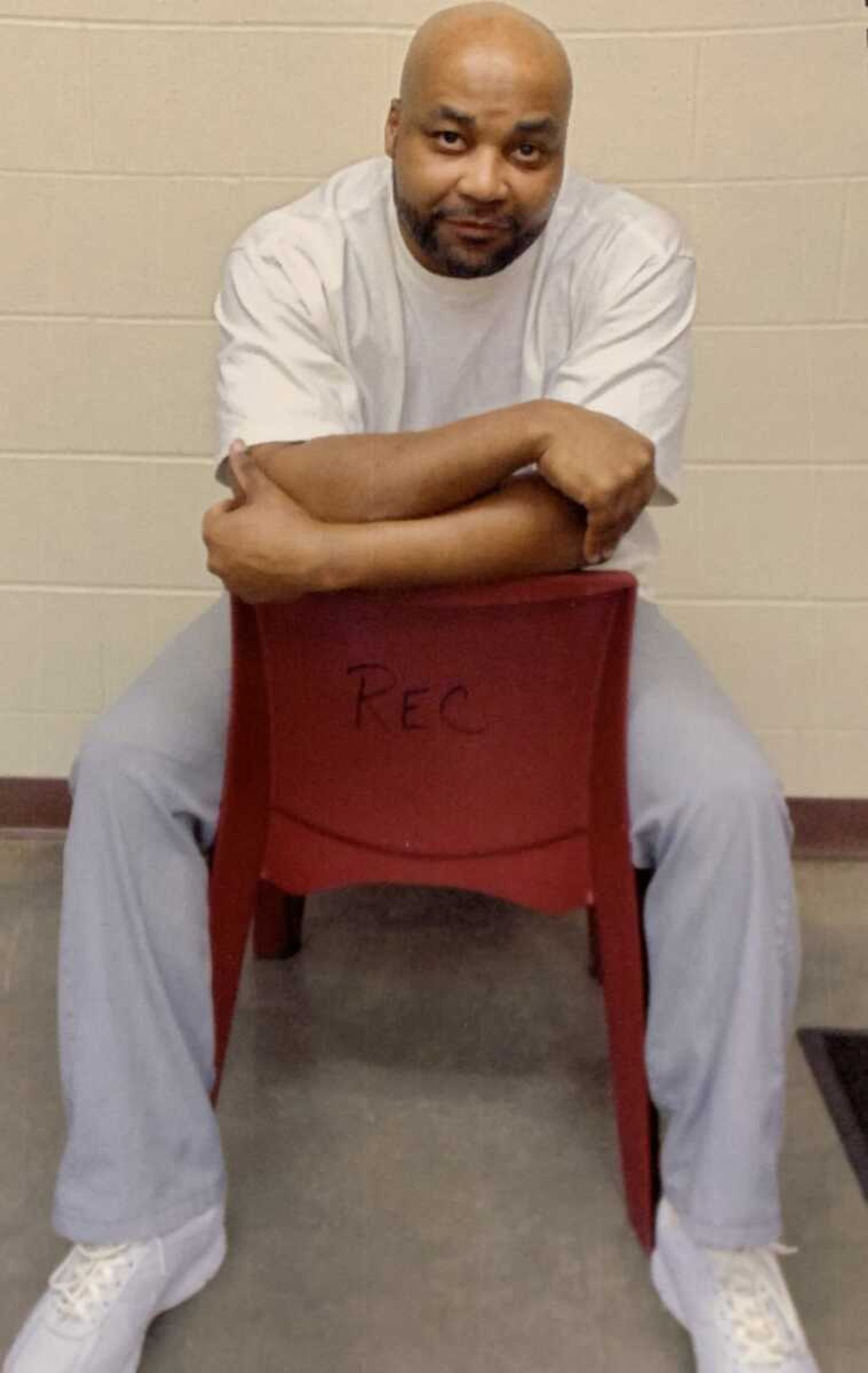

Ronald Clark hopes new evidence prompts Missouri Supreme Court to release him from prison

Prosecutors called it murder. Ronald Clark called it self-defense. Now new evidence supports Clark’s claim and gives him hope the Missouri Supreme Court may free him after decades of incarceration. Clark has spent most of his adult life in jail, convicted of first-degree murder in the fatal shooting of 21-year-old Alvin Ray Spence outside a Charleston, Missouri, community center. The shooting occurred on the evening of Nov. 8, 1994, 25 years ago today...

Prosecutors called it murder. Ronald Clark called it self-defense.

Now new evidence supports Clark’s claim and gives him hope the Missouri Supreme Court may free him after decades of incarceration.

Clark has spent most of his adult life in jail, convicted of first-degree murder in the fatal shooting of 21-year-old Alvin Ray Spence outside a Charleston, Missouri, community center. The shooting occurred on the evening of Nov. 8, 1994, 25 years ago today.

He is serving a life sentence.

The 25-year-old case has drawn accusations of prosecutorial misconduct on the part of the then prosecuting attorney, some of which has been argued unsuccessfully in previous appeals in various courts.

But Clark’s attorney, Mark Abbott of Hallsville, Missouri, said new testimony of witnesses is central to the latest legal effort to free the 43-year-old Clark, who was 18 at the time of the shooting.

Abbott (no relation to the Abbott in the Mischelle Lawless murder case) said he expects to file a habeas corpus petition with the Missouri Supreme Court late this month or early next month.

The new evidence:

- Lamontaye Cortez Williams recanted his 1995 testimony in the murder trial.

- Demetric McCauley said in an affidavit he saw Spence pull a handgun from his coat and Clark tried to grab it.

- Ronald Scott, a cousin of the victim, said in an affidavit the gun went off during a physical altercation between Spence and Clark, but Clark did not shoot Spence from a distance as prosecutors alleged.

- Colinthia Williams, who was 14 at the time of the shooting, said she told officers at the police station she witnessed the altercation and Clark didn’t have a gun, but officers never took her statement.

‘Getting him back’

In a June 17, 2019, videotaped deposition, Charleston resident Lamontaye Williams said he and other witnesses at the July 1995 trial in Mississippi County falsely testified they saw Clark shoot Spence because they were motivated by revenge over the death of their friend.

“So that was our way of getting him back,” Williams stated.

Williams said he witnessed Spence and Clark fighting and heard shots, but did not see Clark fire the shots.

“So to sit here and say that he murdered Ray in cold blood, I don’t know,” Williams said, before adding, “it had to have been in self-defense.”

Williams stated, “I just wanted revenge for Ray. That’s all I wanted was revenge.”

Abbott said, “It takes a lot of guts to come forward and admit you made up a story to send someone to prison for life.”

McCauley said he witnessed the incident, but did not come forward until now because his family and Spence’s family were close friends.

“I heard shots, but I did not know who got shot at first,” he stated in the affidavit.

Scott stated in his affidavit he did not see the gun.

“The gun went off when they were struggling,” he explained in the document.

Abbott said Scott’s testimony is “contrary to the prosecution’s version of things. And, of course, it would have been contrary to a murder 1 conviction.”

Abbott said evidence shows the altercation began because Spence was angry with Mark Clark, Ronald’s brother, for getting into a fight with Scott.

“Ronald Scott was kind of at the center of this thing, so he didn’t want to come forward,” Abbott said.

Colinthia Williams, who, according to Abbott, is not related to Lamontaye Williams, gave a videotaped statement in June at the Mississippi County courthouse.

The Cape Girardeau resident formerly lived in Charleston. She said in her deposition she witnessed the altercation outside the Bowden Civic Center, formerly Lincoln School, and heard a shot fired.

She told Abbott she did not see the gun, but later saw Spence’s brother remove something from the victim’s coat.

Police never recovered the weapon.

She said she tried to make a statement to police after the shooting. Officers told her they would get back to her later, but never did, she said.

Abbott said there were numerous problems with the trial itself.

Confused juror

“There was at least one juror who reached out to the (Clark) family, but then refused to talk to me,” Abbott said.

The juror in the 1995 trial told the family years ago she was confused by the jury instructions and thought the jury was convicting him of manslaughter, Abbott said.

He said he drove to Charleston to speak with the woman only to learn she had decided not to speak to him.

“There was a call from the sheriff’s department in Mississippi County threatening to arrest me if I ‘harassed another juror,’” Abbott recalled.

“There have been an alarming number of people who have suddenly changed their minds in this case,” he said.

Jury instructions in Missouri are often confusing, according to Abbott.

“They are a high producer of errors in trials. They are a mess,” he said.

In Clark’s trial, jury instructions were amended in the middle of jury deliberations, according to court records.

“It is yet another one of those strange, bizarre things that happened,” Abbott said.

Alleged misconduct

Then there is the allegation of prosecutorial misconduct, which was raised unsuccessfully in previous appeals.

The misconduct allegation centers around a black jacket, allegedly worn by Spence at the time of the shooting.

The prosecution showed the jury the jacket without previously disclosing it to the defense before trial.

Clark’s public defender at the time, Gary Robbins, asked for a mistrial, arguing it was “improper, prejudicial,” according to the trial transcript.

But the prosecution argued no advance disclosure was required since it was used as rebuttal evidence.

Abbott said there was an “argument” at the beginning of the trial over whether the gun discharged while the two men were wrestling or whether Spence was shot from several feet away.

“Clearly, the physical evidence at the scene should have been turned over,“ Abbott said.

“I don’t want to call somebody malicious. I don’t want to call it intentional misconduct, but prosecutorial misconduct is pretty damning,” he said.

Even if not intentional, it still rises to the level of misconduct, according to Abbott.

“I think what someone was wearing during an altercation in which he got killed, I think that is important,” he said.

Clark, who is black, was convicted by an all-white jury. During jury selection, the public defender objected to the prosecution striking black potential jurors from the list, but the trial judge concluded those strikes were “race neutral.”

Abbott doesn’t believe the issue is appealable now. But if Clark’s trial were held today with an all-white jury, it would have been an issue in any appeal, he said.

“I believe today if that case was in the Court of Appeals, they would have a problem with it,” he said.

Teresa Bright-Pearson, who now serves as Cape Girardeau’s municipal judge, prosecuted Clark.

She declined to discuss the case or the allegation of prosecutorial misconduct on her part.

“As a judge, we shouldn’t comment on any pending cases or past cases,” she said.

“I just don’t think it is appropriate for me to get involved in the case at this point,” she said. “I will let the record speak for itself.”

Abbott said the Supreme Court has “a lot of leeway” when it comes to the appeal.

“The Supreme Court could release him. I think they could just order a new trial,” he said.

Do you like stories about government and courts? Keep up with the latest news by signing up for our daily morning headline email. Go to www.semissourian.com/newsletters to find out more.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.