Extreme sense of loss can lead to grief-fueled substance use disorder

Eight years ago, Amy Schroeder-White's boyfriend of several years, Ryan, was murdered during a drug deal.

Editor's note: This article contains references to murder, rape, substance use disorder, depression, suicide ideation, grief and other possibly alarming content. If you are experiencing any of the above, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 (TALK) or SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-4357 (HELP). If you or someone you know needs help navigating grief, visit griefresourcenetwork.com/crisis-center/hotlines/ to find a comprehensive list of hotlines and other resources. To protect the identity and safety of sources, names have been changed within the article.

Eight years ago, Amy Schroeder-White's boyfriend of several years, Ryan, was murdered during a drug deal.

After years committed to setting Ryan's life on the straight and narrow, a devastating scam by a former employer had left the couple in a tough financial position. So Ryan had been selling pseudoephedrine pills to help support Schroeder-White and the couple's then 4-year-old son.

Now 39 years old and living in Wright City, Missouri, Schroeder-White said she had told Ryan it was a bad idea to get caught up in selling the drugs, but she said he couldn't walk away from the money.

By phone Thursday, Schroeder-White said she remembers the gut feeling she had that night: "something doesn't seem right about this."

Her worst fears were realized when the police showed up at her house in the middle of the night to inform her of the shooting.

He was now on life support, having been robbed and shot in the head. Twelve hours later, he was gone.

The violent, sudden way Ryan was killed completely overwhelmed Schroder-White.

"It was almost surreal to me. I had known how using drugs made me feel, and I knew that I could put every other feeling aside by doing that. I couldn't stop crying," Schroeder-White said. "The only thing I could do to not cry, to function, to go through my life ... was get high."

Her grief became a full-fledged substance use disorder, and it devastated everything in its wake.

Substance use disorder, the clinical term for drug addiction, is a disease that affects a person's brain and behavior and leads to an inability to control the use of a drug or medication.

Schroeder-White admitted by phone Thursday she was no stranger to drugs when she began using heavily. But back then, it was recreational.

"Though I had gotten high in the past, it was a whole new, different thing for me now, because now I was doing it to not feel," she said. "Now, I had to have [drugs] because if I didn't ... I was a complete emotional disaster."

The need to use drugs is an effect of the chemical imbalance taking place in the brain for someone with a substance use disorder.

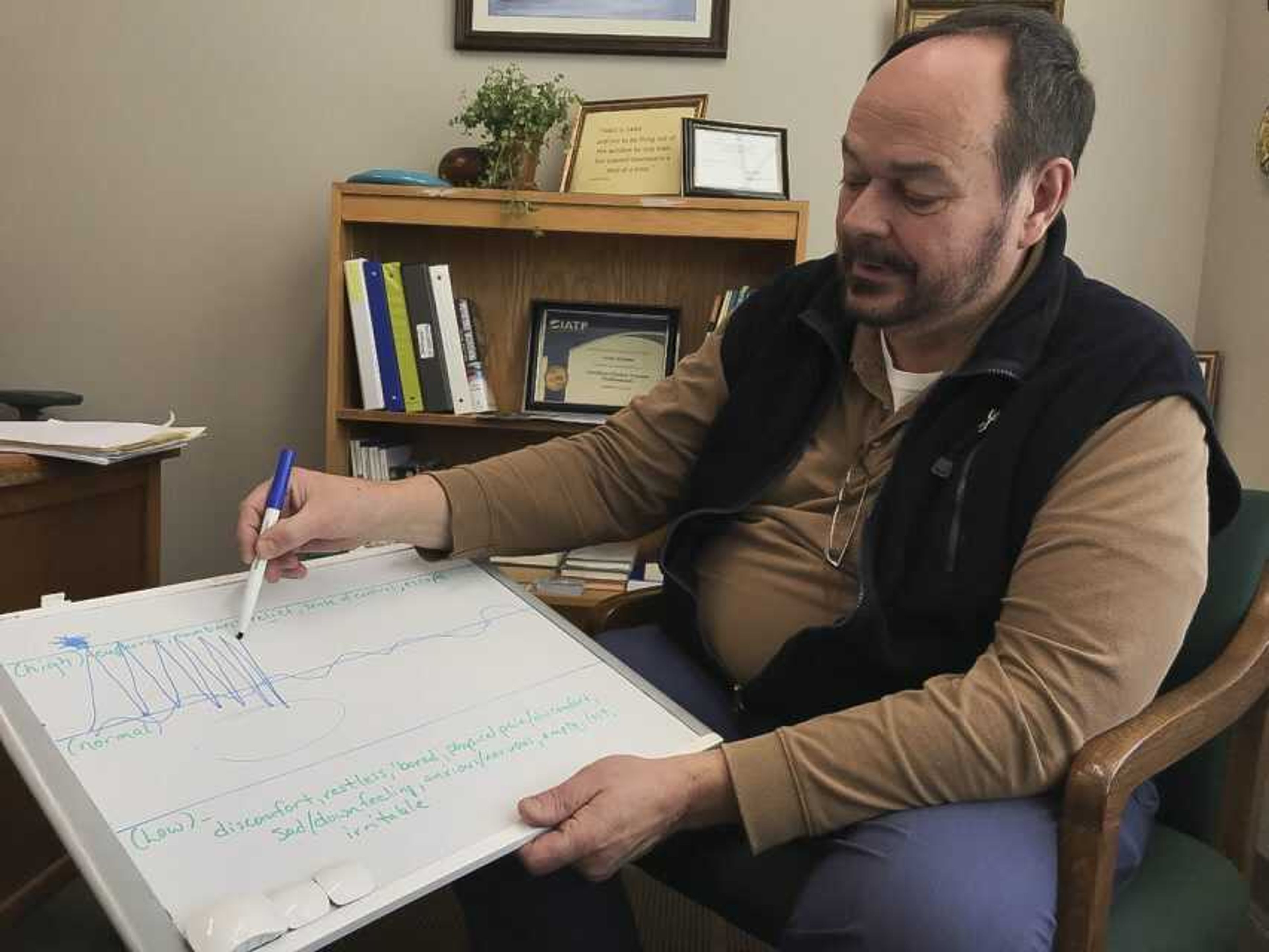

"The expression that is heard a lot lately is that addiction tends to hijack the pleasure centers of the brain," said John Nimmo, a substance use counselor at Southeast Missouri State University's Counseling and Disability Services. "Normally, we respond to different situations with a pleasurable response that involves dopamine production. ... With an addictive substance and an addictive process, it can be such an intense reaction that those other stimuli, over time, just don't have the same effect."

For someone with substance use disorder, the ability to produce dopamine becomes -- for the time during which the drug is actively used -- somewhat impossible without the drug use.

"Over time, the body stops producing things normally," Nimmo said. "The chemicals normally produced day by day that help us feel good and help us feel well and OK tend to diminish, and the body tends to defer to the chemical you're introducing."

In addition to regular substance use, Schroeder-White began obtaining larger quantities of the drug and selling what she didn't use in order to pay for the habit.

"Before I knew it, I didn't know if I was addicted to doing the drug or to making the money," she said.

Eventually, police found "a very large amount" of methamphetamine in her home, and her children were taken into state custody. That was when she truly met "rock bottom."

"I had been numb for so long, and now it was like, 'Man, I have to actually face everything,'" she said. "I remember dropping to my knees and saying, 'God, please help me. Please help me.'"

Schroeder-White went through years of family treatment court -- including trauma counseling, family therapy counseling and intensive outpatient treatment -- in order to reunite her family. She also began a 12-step program, a resource that continues to be "a huge part" of her recovery today.

"The support that I receive from the 12-step program I'm in is phenomenal," she said.

Her sobriety date is fast-approaching three years, as she said she hasn't used a drug since Jan. 17, 2017. She is married with two children, and Schroeder-White said she recently earned her state credential to become a substance use counselor.

The message she most wants to share with others is one of hope.

"There is a light at the end of the tunnel, no matter how dark it gets," she said. "There's a better way to live."

And while she has since created a better life for herself and her family, she continues to grieve Ryan's death.

"The grief never goes away, but it does get easier. It does get so much easier," she said. "When it feels like you're hurting so bad that it's never going to go away, it does get better."

A 'desperate situation'

Schroeder-White's experience with grief and substance use isn't uncommon.

According to SAMHSA's most recent report, approximately 20.3 million people aged 12 or older in the United States had a substance use disorder in 2018, including 14.8 million people who had an alcohol use disorder and 8.1 million people who had an illicit drug use disorder.

Anyone can develop a substance use disorder, according to the MayoClinic, but there are risk factors that can affect the likelihood and speed of its development, including a family history of addiction, a pre-existing mental health disorder, peer pressure, lack of family involvement, early-life drug use and taking highly addictive drugs such as opioid painkillers.

Many people experiencing loss may be looking for a way to numb the pain, according to Cape Girardeau licensed professional counselor Becky Peters, of Becky Peters Counseling.

"One of the reasons [why people abuse drugs or alcohol] is to numb or cover up grief or loss," Peters said. "Because they don't know how to get out of it and fix it, and they don't want to feel it anymore."

At some point in a case of a substance use disorder, the reason to use stops being about the ability to achieve the state of the euphoria associated with a "high," and more about survival, Nimmo said.

"It's a pretty desperate situation."

Unlike many health issues, substance use disorder comes with a stigma: Why can't people just stop using?

"Some people believe that the negative consequences from drug use will cause you to stop," Nimmo said. "And that's generally the way it works. If you get negative consequences from some behavior, generally, you'll stop. But with an addiction, that's the definition of it: 'I get those consequences, but I can't stop.'"

'It can happen to anybody'

When Jane Smith -- whose true name and age have been omitted to protect her safety -- was a college student, she was raped by a friend with whom she had been on a few dates. Smith, born and raised in Cape Girardeau, said her rapist kept in touch with her for months after the assault.

He was wracked with guilt, Smith said, and constantly told her he would take his own life as a result of the pain he felt. So, she found herself feeling obligated to relieve some of his pain.

"It was some pretty intense psychological abuse there," she said. "It is not my job to make my rapist feel better."

Smith decided to cut off all contact with her assailant. She filed a Title IX report with her school on a Friday and by the following Monday, she had gotten word of his death.

"I was absolutely torn apart," she said, remembering her initial feelings associated with the incident. "I was not functional."

Smith began consuming alcohol to numb the pain, an activity she said was totally uncharacteristic.

"Everybody drinks in college," she said, "and I just didn't. I didn't even want to. It wasn't a temptation."

Turning to substance use when faced with overwhelming grief, Peters explained, can be a way to numb emotional pain. But it can also be a coping mechanism to mentally escape the loss for a little while.

"As humans, we don't like discomfort, and we like to get away from discomfort if we can," Nimmo said. "And sometimes the ways we do it are functional, and sometimes they're not functional."

For Smith, there were a few times after the death when drinking to cope became dangerous.

She remembered a time when, upon arriving at work, she was still intoxicated from the night before. Another time, she blacked out, lost several hours and awoke to find furniture broken, evidently by her own hands.

"Honestly, it's six hours that I don't have to remember how miserable I felt," she said, recalling her initial response to the blackout episode. "So, I didn't. It didn't bother me. I was drinking to not feel so powerless."

Once, she even took a final exam for school still drunk but noted she'd still managed to earn good marks.

But for Smith, whose academic career had always been her highest priority, realizing she wasn't sober in the midst of a final exam was "the last tipping point."

"I was like, all right, I've got to consciously make some changes or else this is going to be a real problem," she remembered.

Smith said she was able to walk away from substance use with the help of self-discipline, "a lot of therapy" and support from close friends.

"I grew up in a wonderful, well-off family with no exposure to alcoholism, with no exposure to smoking, with no exposure to drug use," she said. "I had no risk factors. ... But when this happened, even from a place of such low risk, I spiraled. And alcohol is a really easy thing to turn to when you spiral."

To combat such a spiral, she said, it's important to reach out and to be aware of the warning signs.

"I believe if I hadn't stopped myself after a few months ... I could've ended up addicted to nicotine and an alcoholic," Smith said. "I was so close. It can happen to anybody."

When grief is invalidated

For some, grief can lead to lifelong mental health issues such as anxiety and depression, as was the case for 22-year-old Shea Dillon.

When Dillon was a child, her godmother was like her "other mom."

She was close college friends with Dillon's mother and lived in Chicago. Along with another friend of her mom and her children, Dillon said her family used to pile into a vehicle and hit the road to pay her godmother a visit.

"She would come visit us in St. Louis at my grandparent's house," Dillon said. "And she worked for Mary Kay, so I remember she would always bring me and my sister makeup and stuff. It was great. It was how we bonded."

So when she disappeared from Dillon's life without so much as a goodbye, confusion, pain and a "deep sense of abandonment" set in.

Dillon has since forgiven her mother for whom she initially blamed the sudden and unexplained loss of her godmother. She now studies English writing at Southeast Missouri State University, but high school in St. James, Missouri, was hard for Dillon; she said it was difficult to trust people or feel a real connection to anyone.

"I guess I pushed people away," she said. "I didn't really want to trust anybody because I just had it in my mind that nobody was going to stay in my life permanently and there was nothing I could do about it."

Dillon was 18 years old when she was diagnosed with depression and anxiety, but she said "it definitely started in middle school and just progressively got worse."

Many years after the fact, Dillon said she learned the truth of what had happened with her godmother. The old friends had suffered a falling out, and her godmother had decided to close the door on their long-standing friendship.

"It really hurt that it was her choice to leave and hers alone," Dillon said.

The type of loss Dillon experienced can be classified as "disenfranchised grief," or grief that isn't openly acknowledged, socially accepted or publicly mourned.

This lack of acknowledgment may be due to several factors, including that the loss isn't seen as being worthy of grief, because of a stigma associated with the relationship or with the death. It can also be because the person grieving is not recognized as a traditional griever or even because the way in which someone grieves is stigmatized.

"No one would really care because it wasn't my actual mom," Dillon said of her godmother. "I felt like if I talked about it then people would try to invalidate those feelings because she wasn't my blood relative."

But loss, as Nimmo pointed out, can be many things.

"Sometimes you get so consumed in that grief that you can't help yourself anymore," Nimmo said. "We can't talk to ourselves positively and say, 'Come on, let's get past this.' A lot of times we just don't have the resources. ... And sometimes we need that other person or resource to help us."

Until talking frankly with her mother about what she was going through in her grief and depression, Dillon said she "felt crazy" about the emotions she had experienced.

"You know how you see something and nobody else sees it and you just feel crazy?" she asked Wednesday. "That's basically how I felt."

Sometimes, Peters said, when people don't know what to say or do for a grieving person, they will often decide to stay away. But that may only drive home the feeling of isolation a grieving person may experience.

"What we know is you don't have to say anything. Just come sit in their house and have a cup of coffee or just sit next to them; just be present," Peters said. "And just because they don't talk about it doesn't mean they don't need help."

Now, Dillon and her mother have a stronger connection because of the ability to talk about the grief they both felt over the end of an important friendship.

"It has helped me learn to love my mom more," she said. "I didn't really understand what loving her meant because I didn't understand her, and I didn't understand where she was coming from [on] this. Even though I loved her before, I love her so much more now, knowing that we went through the same kinds of grief."

Part 4 will publish Jan. 19 and focus on faith's role in navigating grief and loss.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.