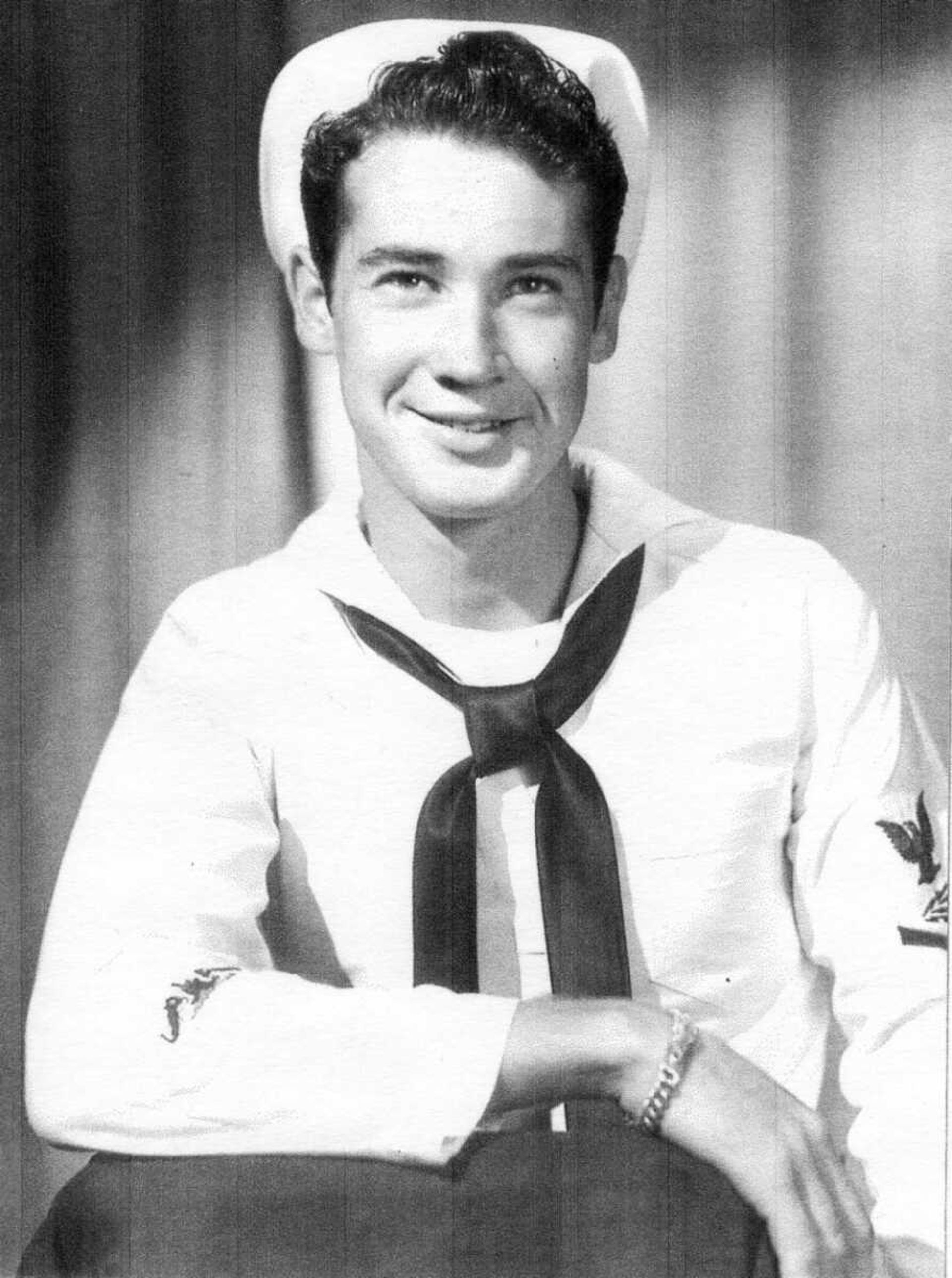

Navy veteran Vance Combs looks back on time in submarine during World War II

On Vance Combs’ 95th birthday Monday, the sun is shining, birds are singing at his Cape Girardeau home. His wife and son are at the house, ready to take him out to lunch in a couple of hours. It’s a far cry from where he was 75 years ago, serving on the USS Cobia, a submarine off the coast of Japan, during the military campaign that would culminate in the island of Iwo Jima’s capture...

On Vance Combs’ 95th birthday Monday, the sun is shining, birds are singing at his Cape Girardeau home. His wife and son are at the house, ready to take him out to lunch in a couple of hours.

It’s a far cry from where he was 75 years ago, serving on the USS Cobia, a submarine off the coast of Japan, during the military campaign that would culminate in the island of Iwo Jima’s capture.

The Battle of Iwo Jima began Feb. 19, 1945, and lasted until March 26 of that year. The Associated Press photo of Marines raising a flag above Mount Suribachi is iconic, and a familiar emblem of World War II.

But there’s more to the story.

Growing up in tiny Reading, Iowa, Combs said, there was no doubt in his mind he wanted to join the Navy. He enlisted at age 17, having just completed a course for the Army’s Signal Corps, and said he figured he’d pursue a radio operator position with the Navy.

After three months of studying at the University of Idaho, he said, the top 10% of the class were offered a chance to volunteer for submarine duty.

“I thought, ‘Wow, hm, that’s a little different. Well, let’s go,’” Combs said.

At New London, Connecticut, Combs said, he underwent a physical and psychological exam.

“Submarines are cramped, and if you have any tendency towards claustrophobia, this is no place to be,” he explained.

Combs’ duty station was aboard the USS Cobia, a brand-new submarine, or “boat.”

Combs said by the time he was assigned to the Cobia, all of the radio operator positions were full, so he became the lookout — what he called the best job, since he was in the sunshine and fresh air.

He spent two war patrols as lookout, and one in the radio room, he said.

The Cobia arrived in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in June 1944. After a fuel stop at Midway Island, the Cobia arrived at its assigned area: a string of volcanic islands south of Japan.

Several of those islands included the word “Jima” in their names, Combs said.

“Now we know about Iwo Jima, but we didn’t then,” Combs said.

“We got in the area and we did pretty well,” he remembered. The Cobia sank 13 Japanese ships, he said, and one of those ships turned out to be particularly significant.

“While we’re in that area, we sink a particular ship and go on our way. That’s normal course. You sink a ship, they discharge you (with explosives), hoping to get you after you’ve done them,” Combs said.

“It was only later, after the war, that somebody, probably (in) Washington (D.C.), launched a full record of this,” Combs said. In identifying that ship, later, it came out that it had been carrying a full load of tanks, crews and mining engineers, likely to help with the island’s tunnel projects.

In the mid-1980s, Combs said, at a reunion at the Wisconsin Maritime Museum in Manitowoc, members of the 5th Marine Division Iwo Jima survivors’ group presented the Cobia’s crew with a commendation, thanking them for their role in the fight.

“Maybe we did have a small part in the final part of the victory over Iwo Jima,” Combs said.

Over the years, Combs said, he’s gotten questions about how anyone could live in a submarine, and why.

“I don’t have a good answer,” he said, aside from the top-10% designation — and the 50% additional hazard pay.

“And it was hazardous duty, there’s no doubt about it,” Combs said. He said after the war, it was figured submarine crew members were six times more likely to die.

“Come to find out, we earned it,” he said.

What was it like on the submarine? “Crowded,” he said. And this was before submarines were able to create their own oxygen, he said. “You’d go in (underwater) at daybreak, and you wouldn’t surface until 8 p.m., and you’d been breathing the same air the entire time,” Combs said. And nearly everyone on board smoked cigarettes, he added. “The air was so deficient in oxygen, a match wouldn’t burn. We got around that with electric cigarette lighters.”

After the submarine would surface at night, the crew would throw open the hatches and turn on the big diesel engines, Combs said. “That was nice.”

There were only two times he thought he was going to die, Combs said, “so that wasn’t too bad.”

First time, he was a mess cook.

“Everyone has to rotate through if they’re junior,” Combs said. Mess cooks helped the cooks, washed dishes, cleaned up, he said. “Come nighttime, we surface and have to get rid of the trash and garbage. The guy on the bottom would hoist the gunny sack up to topside. We were in Bashi Channel ... It was really rough, the boat was pitching and rolling. We were constantly having to dive because, by that time, the Japanese had radar on their aircraft. Every time we’d get an aircraft beamed in on us, on radio, when they had us painted, we could tell it, and we’d dive.

“Well, I was topside, throwing those bags over the side, boat is pitching and rocking, and the door that I came through to get out on the deck slammed shut. Pretty quick, I hear the word, ‘Clear the bridge, dive, dive,’ so of course I hustle over to the door and it won’t open — ‘Oh, dear.’ Finally, it occurred to me to check around, and sure enough one of the other doors had fallen. The water was already high, but they were waiting for me, so I got down without even getting my feet wet — but I was sure scared.”

Another harrowing moment came after the Cobia had sunk a couple of ships, and the destroyers were in pursuit.

“They were really good,” he said. “There were three of them. They had us on sound, pinging us, and they were good at it.”

Two of the destroyers were pinging and a third dropping depth charges as he came, Combs said.

“I figured, ‘This is it,’” he recalled.

But it wasn’t.

“I can only assume — I suspect they set their depth charges too shallow,” Combs said. “We were down 300 or 400 feet, as low as we can go. I thought for sure we had it on that, but no. You do what you have to do. You do your job. Of course you’re scared. But you do your job.”

Right after the war, Combs spent some time at odd jobs on the West Coast, including a farm in Oregon and a dairy farm in Northern California.

An uncle of his had a hatchery in Missouri, Combs said, so he spent about six years working there before he joined up with the Federal Aviation Agency, now Administration, and was stationed at the Cape Girardeau Regional Airport. Not in the tower, he said, but furnishing weather reports to the pilots — conditions at the destination and en route.

He and his wife, June, married in 1950, and raised three children together.

“War was an adventure,” Combs said. “I certainly don’t regret any time in it.”

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.