Historic Preservation: What's on Dr. Steven Hoffman's mind

Dr. Steven Hoffman, historic preservation program coordinator and professor of history and anthropology at Southeast Missouri State University, has done much to save the history of Cape Girardeau since his arrival on the scene 25 years ago. Through his own efforts and the efforts of his students, he has shepherded more than 10 Cape Girardeau buildings and districts onto the National Register of Historic Places, among them the St. ...

Dr. Steven Hoffman, historic preservation program coordinator and professor of history and anthropology at Southeast Missouri State University, has done much to save the history of Cape Girardeau since his arrival on the scene 25 years ago. Through his own efforts and the efforts of his students, he has shepherded more than 10 Cape Girardeau buildings and districts onto the National Register of Historic Places, among them the St. James AME Church, Court of Common Pleas and Southeast Missourian building. He has formed the minds and historic preservation dispositions of numerous students -- some of whom have also become important players in the preservation of historic buildings in Southeast Missouri post-graduation -- through teaching courses about historic preservation, built environment studies, downtown revitalization and African American history. And he has moved the conversation around historic preservation forward both locally and nationally through countless articles he's written on American social history, urban history, African American history and suburbanization. He has served as the president of the Board of Directors for Missouri Main Street Connections since January 2009 and secretary of the National Council for Preservation Education since 2010; he formerly served as an advisor to the executive committee of Old Town Cape.

For this "Infrastructure" issue of B Magazine, we sat down with Hoffman to pick his brain about the historic preservation projects he believes are most urgent in Cape Girardeau, other towns that have successfully rehabbed old buildings into viable economic projects and what might be a similar path forward here in Southeast Missouri. We edited the conversation for length and clarity. Here's what he had to say.

What is on your mind in regards to historic preservation in Cape Girardeau right now?

We have these buildings that have value, even if we don't necessarily see it today. And once they're gone, they're gone. I am a strong advocate for if we're going to build today, we should build quality, and we should build something that is going to be worth preserving and will not only be around in 50 or 75 years but is something that people will want to preserve. I was very pleased with the direction the redevelopment of the Courthouse of Common Pleas seems to be taking in that there does seem to be a commitment to quality that will be representative of the quality of our community and an investment in the future. They're not going to just look at the bottom line and build the cheapest thing, but in fact they're going to build something that we can be proud of and recognize the history that's there and what's needed to get there with some new construction. I think it should speak to the age that we are in. Let's not build something that looks old; let's build something that fits in with what we have but looks like today.

Are there specifics about the courthouse in terms of quality and things that we can look forward to seeing?

It's all in the beginning stages, so my comments are kind of based on a conversation with the preservation architect that's part of this larger team, but her sense is that the client -- which for her is the general contractor and the City -- is interested in a quality project that reflects the importance of the site and to build something for posterity.

For example, the Marquette Tower -- could you build this much square footage office space less expensively? Yes. Could you build this quality building with these finishes new for the cost of rehabbing it? You couldn't. You couldn't do it. And this space is unique, and it's distinctive, and it helps Cape Girardeau stand out as its own place, a place that people would want to be. The research suggests that it's communities that people feel a sense of attachment to that are stronger. They're more vibrant, they're more economically successful.

So how do you make a place "sticky?" You have community organizations, you have ways of getting involved, but you also have distinctive places. So a place like the Marquette Tower will allow us to remember events we experience in them and have positive associations with it. The more distinctive places we have like that, the easier it is for a wide variety of people to develop attachment to place, which is going to pay dividends in the long run. They're not going to realize it -- it's not going to be a conscious thing -- but they're going to be more attached to Cape Girardeau as a positive place and want to stay here and develop their businesses here and raise their families here in part because they have this positive experience.

What are the things that keep you up at night in regards to historic preservation in Cape Girardeau?

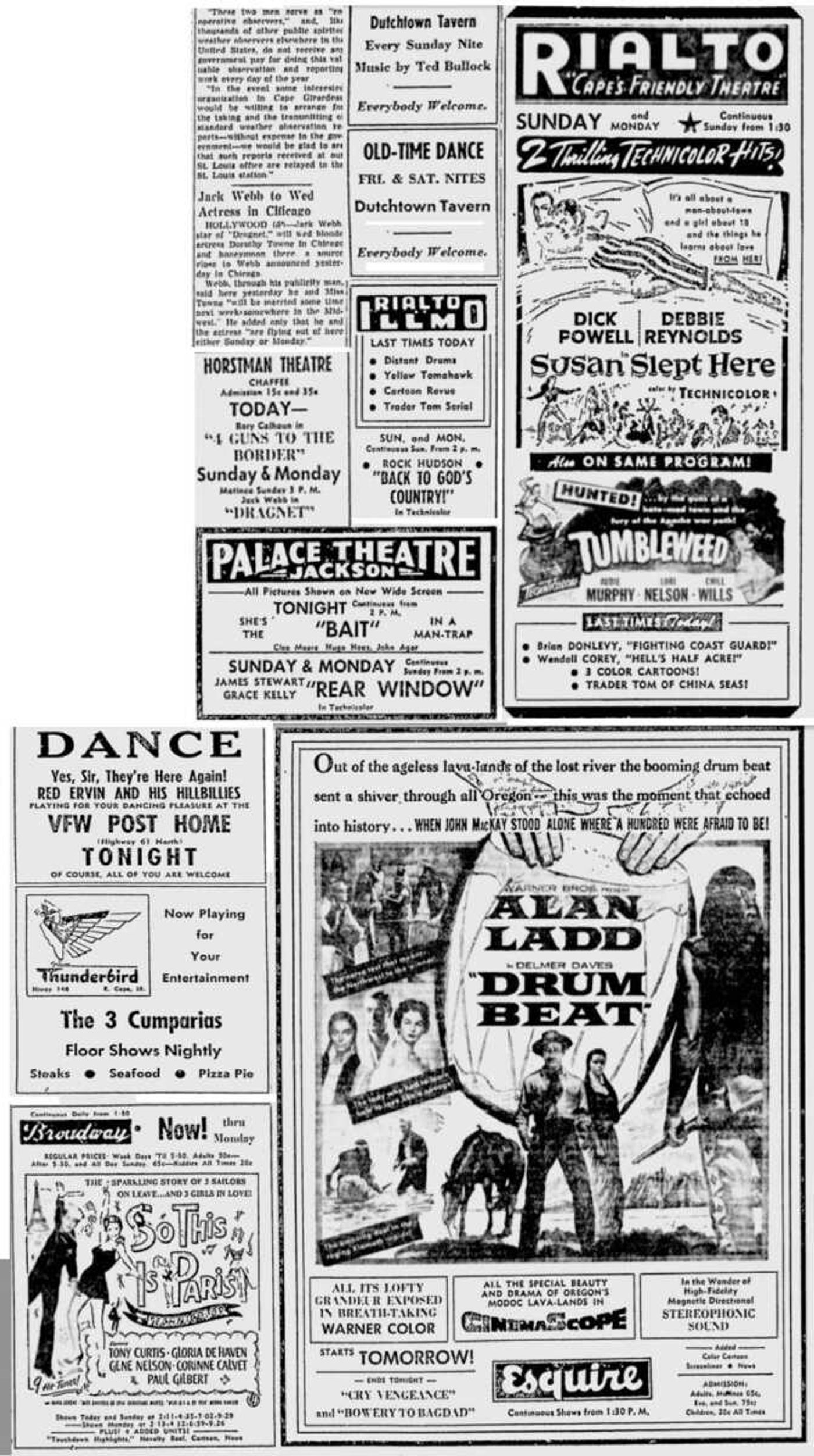

The things that keep me up at night are the theaters. In other places, there are historic theaters and people figure out a way to make them work. We need to do that because 20 years from now, we're going to be really excited that we have the Broadway Theater and whatever's going on in that space that will allow us to say, 'You know what, Cape Girardeau's pretty cool.' We're going to go to Top of the Marq, pass through the Marquette Tower lobby, go to the Broadway Theater, which you just can't do anywhere else. And if we let that fall down, it's probably going to be a grassy, empty lot for how long? It's never going to have what we have now. Same thing with The Esquire Theater. These are two properties that add a dimension to our community that when it's gone, we're not going to be able to reproduce that.

The problem with preservation, rehabilitation, is that you have this gap. How do you fill the gap? Jumping over that gap sometimes is risky. One of the things I've noticed about the Cape Girardeau investment community is that they're extremely risk-averse. And I understand, nobody likes risk. But also without risk, there's no reward. Our investment community is taking risks all the time, but they do it with projects that they're familiar with and that they know, and so they are comfortable with that risk, and this is just new to them. It may not in actuality be any riskier, but they're not as comfortable with it because they're not as familiar with it. If we had those properties if we were in St. Louis, we wouldn't have any trouble trying to find the money to redo them. And it's not that we don't have the population or the need for the space, all those things to try to minimize the risk.

How can developers and investors leap over that gap?

I think it's probably a combination of things. I think that partly it's buying into a creative vision of the future and trying to get people to see that. That requires patient capital, and I think we do certainly have portions of our investment community that have patience. I think the Marquette Tower is a project that took advantage of patient capital, people who said, 'I'm going to put some money in that. I'm probably not going to make a lot of money, and I'm probably not going to make a lot of money really fast, but I don't want to lose any money, I want to make some money, and so I see the value to the community,' and they're able to balance that out.

I think if we could convince more people to actually believe that it can happen, if it is successful in 20 years, think about what the value to the city would be of having those two theater properties pay property tax that they're not really paying now, generating sales tax, generating quality of life. Quality of life is really hard to measure, but it's easier to sell office space in the Marquette Tower if Cape Girardeau has higher quality of life than a lower one, so there's all kinds of advantages.

If you then believe that, then I think you start getting more creative about 'How do we bridge that gap?' There are some tools out there that are clunkier to use than they should be -- the federal historic preservation tax credit is guaranteed. It's clunky, you've got another voice in the decision-making process that slows things down, but it's there for use. The state credit is all over the place, but if you're patient, you can take advantage of that. Locally, we have the TIF financing as an incentive. I think we could try to explore other kinds of incentives, too.

It's like giving up a child, choosing one theater over the other from a preservation point-of-view between The Esquire and The Broadway Theaters. Which one would you choose right now in terms of value to Cape Girardeau?

Well, that's a very good question because it's on the table, and there are different ways to answer it. Honestly, I think that long-term, The Broadway has more value than The Esquire because The Broadway is larger, it's more flexible ... but also, The Broadway is larger. So realistically, I think the developer's idea of proving the concept with The Esquire in a smaller, manageable project and then turning attention to The Broadway was the right way to go, to kind of ladder people's expectations and belief. So what do I think has more value? I think The Broadway if we had to choose one. But probably if we end up going down that route, it's going to be which one. Doing one is better than doing none, and so the smaller project is probably the one that will get done. You know, half a loaf is better than no loaf.

How do you help people to bridge that understanding of what The Broadway can be? Are there examples that we could point to?

There are examples, but the examples always come back to the fact that every community is different; every project is different. I think one of the things that is consistent is that you need a real champion. You need somebody with vision and a use. I think projects that engage the public tend to be more successful. A lot of people have memories of both of those theaters, and I think that it means something to the public. Right now, there's no real conversation about it; you drive by and 'Oh, that happened,' but there's not real public conversation about it.

I think it was in Owasso, Michigan, and they had a theater of similar age of ours, which had a terrible fire. People think The Broadway is in bad shape; no, it's not. I mean, yes it is, there are some issues, but it's mostly intact. In Owasso, they had a fire, and an arts group took the theater over, started raising funds. Now it's in full operation to do all kinds of things. You know how you go to a theater and all the seats are the same? Well, these are all different-colored seats. It's like, 'Wow, that's cool.' It's kind of a thing in itself. They did a campaign and sold 100 seats for $1,000 each and the donors got their names on the seats. They raised $100,000. Those theaters are sticky. They're like 'Oh, I had my first date there, whatever, just $1,000.' That's small money.

So trying to get the big money to see that it has this potential, in order to make them feel better about stepping over what feels like a wider gap is, I think, the key. With the Main Street America state and national groups that I'm involved with, we went to Iowa and visited several successful towns there. One of the trends in towns that are successful with revitalization efforts is that it comes down to individuals who get a vision. The developer's like, 'Oh, I grew up here and moved away, I moved back, I bought a building, I fixed it up. I encouraged Johnny next door to fix his, now the four of us have bought this other building ...' So it's that personal commitment and vision that we are going to use the resources we have to make this a better place, and we're not going to lose money doing it because we can't afford to do that. We might not make as much money doing it as we could being safer, but as long as we could get a return on our investment, build the quality of life, make this better, we'll see the return in some other ways.

I think for a community like Cape Girardeau -- and we have a chance that I think a lot of people in other communities don't -- if we can build that quality of life, maybe we could keep our kids here. Because if we don't keep our kids here, then we're going to die. Right? So you get people who start thinking about that next generation. So yeah, maybe don't invest in saving these two theaters for you and your retirement benefits; invest in it for your kids so that they don't come home, say, 'Oh, there's nothing to do, I'm going to go to St. Louis.' I think it's important to get people to see that: saving the past is about preserving the future.

Is it important to do these things before the people who have memories at these places are gone, or do you think the younger generation that doesn't have memories at these places is more likely to invest in that and say, 'No, this is important,' even though they don't have memories there, necessarily?

That's a great question, and I think it's both. I think that historic environments increase place attachment for a variety of reasons, and so there are people out there who remember this when it functioned. With the H&H Building, for example, there are people who have experiential attachments to the building and then I think there are a lot of people who don't but who still walk in that lobby and say, 'Life is crazy and hectic, and I want to spend as much time as I can surrounded by cool, interesting architecture and places,' and so we do see a lot of younger people choosing where they want to live and then finding work that works for them rather than GM sending them to so-and-so place. We've kind of seen that shift.

A lot of economic development is about talent attraction. How do you attract talent? Even people who don't have those attachments already recognize sticky environments that are just more fun to be around -- historic, big buildings and the uses of them. So I think that younger people who don't already have attachments are attracted to places where you can more easily form those attachments that are different, that have some unique character, and the places where that can happen more easily are in historic buildings. I'm glad we have Target, but if I took you out there and blindfolded you and spun you around five times and asked you where you are, that's up and down the interstate, that's anywhere. And I think increasingly for young people, that's not really what they want. If they can be in a place that is unique and distinctive, then that's where they want to locate, and if they have the freedom to move where they want to move, they're going to choose one of those places. And so I think it's our job to make Cape Girardeau that. To have Wi-Fi and fiber and coffee shops and places to have conversations like this that just aren't anywhere.

There are two ways to think about the university. When I arrived here 25 years ago, people talked about it and thought about it as a people pump: it drew in people from the region and it trained them and it pumped them out. And with that model, you have all the dying towns of Southeast Missouri, with Cape Girardeau kind of being the last one to turn out the lights before everybody's gone. And that said, I think the way you need to think about it is as a talent magnet. All these talented people come, and they're going to be here in Cape Girardeau for two, three, four years. What can we do to make them stay? We've brought you here; how can we make you stay? We're going to increase the odds of making them stay if we can provide a unique, distinctive environment that's not like anywhere else. How are we going to do that? We're going to do that by rehabbing the buildings that we have. We're not going to do that by building new. We need to have some new, I recognize that, but they can shop at Target anywhere.

How do we get better at being a people magnet?

A lot of it, I believe, is an iterative process that we need to listen to people, which means we need to talk to them. We need to ask them what are the things that they're interested in? I think with young people, we also need to recognize that they may not know, and so we need to do the research on our own: what seems to be working in other places? And then balance that out -- what's working in other places and what are people doing to attract talent, combined with observing the actual behavior that people are doing and talking to them, and then taking that into account and trying to respond to that.

The key ingredient when you're talking about talent attraction is place quality. So let's look at what that means. What are our roles in that? If we identify our role, we need to then try to fulfill it, and I think where we're at in our community is trying to convince other people of their roles. You know, funding is always an issue. And I recognize I'm an academic -- I feel like I'm connected to the real world and I'm realistic and all that stuff, but again, I am who I am. But you know, funding's always an issue, and Cape Girardeau has these pockets of funding. One of them is the Innovation Fund, and everybody always thinks of the Innovation Fund as being radios or technology or something. But how innovative would it be if we bought that building and mothballed it so that we could wait for a developer to come and have it be an income generator in 20 years? That's an innovative use of money, I think.

If we're smart, the City is going to be recognizing that they get nothing from the empty lot, and so if they can find a way to make development happen even if it means stepping outside of the traditional role, that would be a good thing. And I'm not saying spend public money to benefit private property owners, but spend some public money now to control the property, and then not try to make a profit off of it, but instead find the right use for it. If we're asking private capital to invest and be patient, then the City can do the same thing, I think. And we should think about it. I think those are the kinds of things that help narrow that gap, make it more possible.

---

Vintage ads, Southeast Missourian, January 8, 1955

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.