Extension of I-57 to impact national traffic, Poplar Bluff and Arkansas economies

Bill Robison likes maps. He walks into the conference room carrying an easel in his right hand and several maps under his left arm. Robison, the Highway 67 Corporation chairman, makes his introduction, then unfolds the easel. As he shares the maps, he paints the background for a story about a highway...

Bill Robison likes maps.

He walks into the conference room carrying an easel in his right hand and several maps under his left arm.

Robison, the Highway 67 Corporation chairman, makes his introduction, then unfolds the easel. As he shares the maps, he paints the background for a story about a highway.

The story is decades in the making, an 80-year-old vision in progress. But it’s also a story of how leaders and voters in Poplar Bluff, Missouri, recognized the ways maps could change, or at least how they could move the gears of progress a little faster. That vision has put this Southeast Missouri town, and the U.S. 60 corridor, in a position to become the transportation piece connecting Dallas to Chicago.

It’s the story of the future of Interstate 57.

TRAFFIC FLOW

Robison flips through his maps to find one that best tells the larger story. As chairman, Robison fills the role of spokesperson for the Highway 67 Corporation, a quasi-governmental entity structured to oversee the development of Highway 67. Highway 67 has a lot to do with the Interstate 57 project, but the map Robison grabs doesn’t focus on Highway 67. This map shows the entire interstate system of the United States.

The interstate routes are shown with red lines, each with varying thicknesses to represent traffic flow. The thicker the line, the more traffic the interstate carries on a daily basis.

Interstate 40 looks like a thick stroke of lipstick, representing one of the most traveled stretches in the Midwest. The fat, red line connects Little Rock, Arkansas, with Interstate 55 in Memphis, Tennessee. In this area, Robison says I-40 is near capacity, bumper-to-bumper in many parts. Much of the traffic consists of trucks hauling materials from the deep south, specifically from Texas, up to Chicago.

An analysis cited by Robison shows that between 42% and 60% of the traffic on I-40 is truck traffic. The interstate system was designed to move traffic quickly, but I-40 is no longer doing the job; It’s simply not big enough to handle the traffic traveling through. And beyond that, near Memphis, it’s a stretch of road that has been completely shut down in recent years due to flooding and bridge problems.

ROUTE FROM DALLAS

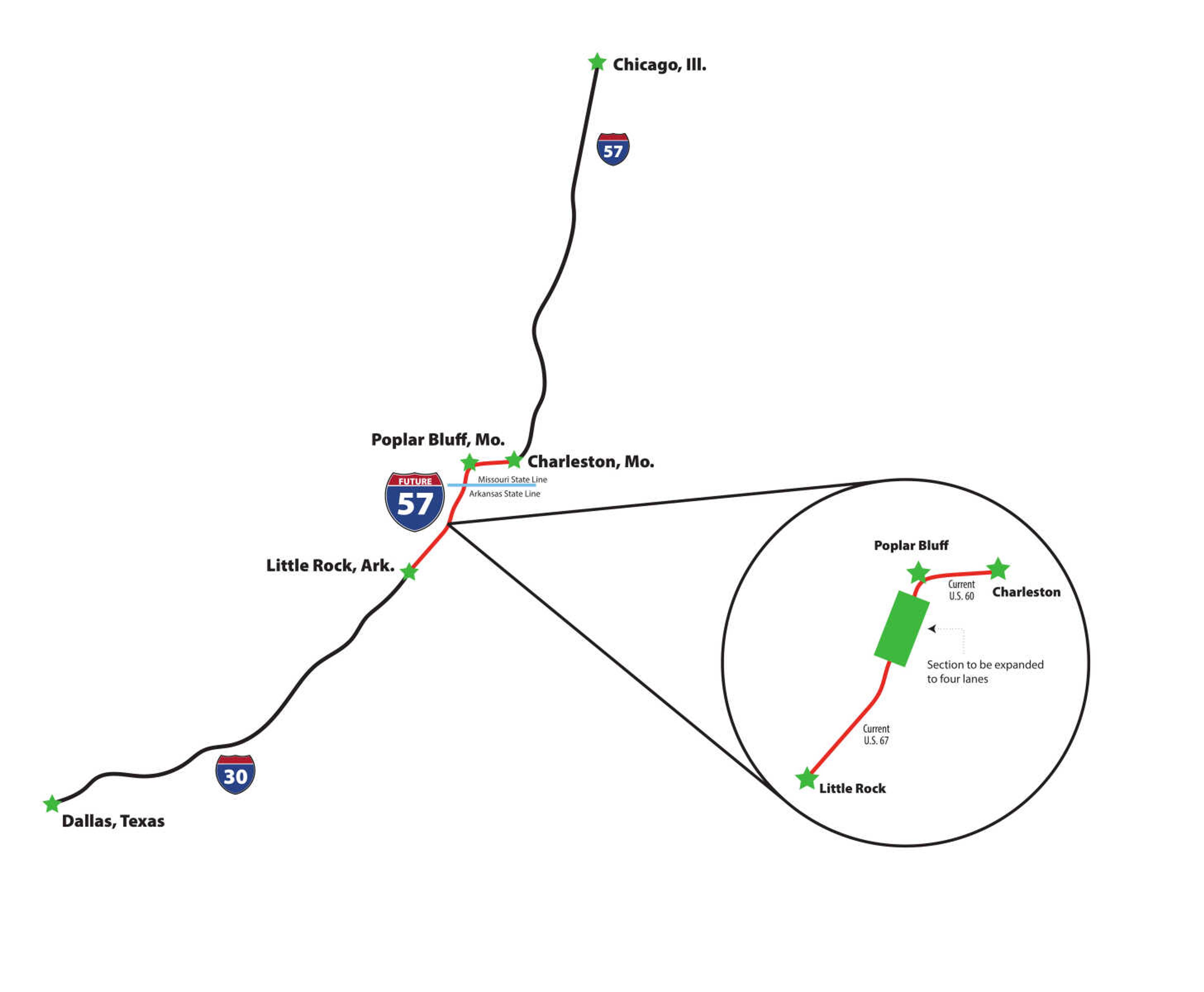

To understand where this story is going, it’s necessary to understand the current map. To the north, I-55 and I-57 meet at Chicago. To the south, the vein and artery meet at Charleston, Missouri, with I-55 bending west to St. Louis, and I-57 bending northeast toward central Illinois. Unlike I-57, which stops at Charleston, I-55 snakes southward on the Missouri side of the Mississippi River, through the Bootheel, into Arkansas, through Tennessee and Mississippi, all the way to New Orleans.

I-55 does the job of connecting Chicago to New Orleans, but currently, no direct route exists from Chicago to Dallas. However, a direct route is close to becoming a reality. In fact, for people like Robison and companies that deliver goods, it’s tantalizingly close.

Robison flips to another map, this one showing the scope of the I-57 project, and its current standing.

He explains how traffic coming from Dallas travels Interstate 30 up to Little Rock, Arkansas, and then most of that traffic heads east on I-40 to Memphis.

Interstate 57 would provide a more-direct north to south Interstate artery right through Poplar Bluff, heading northeast on U.S. 60 through Southeast Missouri to Charleston, Mo. Once complete, I-57 and I-55 would make a huge, curved “X” across the central United States, with Charleston becoming the cross-point of that X. The new I-57 Little Rock and Dallas travelers could avoid Memphis and the “bumper-to-bumper” I-40 traffic.

The project is more than midway through completion. An interstate-grade, four-lane highway already exists from Little Rock, traveling north to Walnut Ridge, Arkansas. That highway is U.S. 67, the same route that connects to Poplar Bluff.

However, Arkansas lacks 42 miles of four-lane to connect with Missouri, and Missouri needs another 12 miles of four-lane to connect with Arkansas. That gap represents what’s currently needed to directly connect Chicago to Dallas.

From Poplar Bluff, U.S. 60 provides a four-lane highway to Charleston to tie into I-57. Modifications need to be made on U.S. 60 to eliminate egress and add interchanges, but the infrastructure — including a few existing interchanges — is in place to handle the traffic.

The path is clear for the future of I-57. All that’s standing in the way is money.

POPLAR BLUFF BEGINNINGS

The potential effects of this interstate connection are enormous.

Motorists from Dallas to Chicago would see benefits in saved travel time. Southeast Missouri, particularly towns on U.S. 60, would see a sizable economic boost from out-of-towners stopping in for fuel, food and lodging. The region’s large farming sector, on both sides of the Mississippi River, could move products more efficiently. As Robison points out: Tyson, Helena, Riceland, ADM, Buchheit, Peco, Cargill and Bunge all have major facilities close to the I-57/US 67/US 60 corridor, the Mississippi River and the railroad network. Many timber companies operate in the Ozarks along the U.S. 60 corridor west of Poplar Bluff.

Poplar Bluff manufacturers such as Briggs and Stratton, Mid-Continent Nail Corporation and Gates Corporation, all would have a much more direct and efficient route for distribution.

All this progress is riding on the expansion of U.S. 67, the last link.

To that end, the Poplar Bluff community has, literally and figuratively, paved the way for this interstate connection.

In 2005, Poplar Bluff voters did something rather unusual. They passed a local tax for a project that extended outside their political boundaries. The tax measure, to sunset after 30 years, would widen U.S. 67 from a two-lane to four-lane in the section between Poplar Bluff and Fredericktown. The tax measure required quite a bit of outside-the-map thinking. Robison explained that special legislation was passed that allowed for such an arrangement with a transportation corporation. The four-lane was funded by an innovative approach. The project was paid off early, long before the tax sunset expired.

The four-lane led to $300 million in private investment in the area, according to Robison, including a manufacturer, which added jobs to the local economy.

In 2019, Poplar Bluff voters approved the expansion of the next leg of U.S. 67. With this vote, enough funding was secured for four more miles of four lanes from the U.S. 67 interchange toward the Arkansas border. Federal funding will need to be secured to finish the final eight, Robison said. Then the ball is in Arkansas’ court.

The move to build the road using local tax dollars was somewhat of a leap of faith. To complete the project, or at least finish it sooner, state and federal dollars were needed. And therein lies Poplar Bluff’s advantage. Unlike other projects without serious funding, dependent on lobbying and sidetracked by competing jurisdictional interests, Poplar Bluff put substantial local tax money on the table. That investment attracted matching state funds. The tax ultimately boosted the project and made Poplar Bluff a larger dot on the map. The tax initiative from Poplar Bluff residents propelled a project that improved transportation for the entire region. The tax has already shown itself to be a success for Poplar Bluff.

ARKANSAS DEVELOPMENT

While I-57 is clearly a significant piece for Southeast Missouri, its impacts might be most felt in Arkansas.

Robison says that Little Rock has seen substantial growth in traffic on U.S. 67. Communities such as Jacksonville, Cabot and Searcy, Arkansas, saw an increase in traffic from 15% to 30% between 2006 and 2016.

Brad Smithee, the District 10 Engineer of the Arkansas Department of Transportation, has had an extended role in nurturing the I-57 project for decades. In fact, Smithee says he saw Arkansas promotional literature from the 1950s asking for support for a stretch of Arkansas four-lane, saying “we must get an interstate corridor from Dallas to St. Louis/Chicago.” Smithee is keenly aware of how slowly projects can move, how reliant they are on federal funds and how difficult it can be to nail down such funding.

“Interstates were born in the concept of national defense by Eisenhower,” Smithee wrote in an emailed response to B Magazine. “But I often wonder if President Eisenhower could have ever imagined how people would travel in 2023, and if people of that time could have possibly imagined the number of freight trucks that would be on the roads today moving goods around the U.S. I certainly doubt they had any idea. In stating this, an interstate is far more than a road from A to B. It provides a corridor of economy, potential and a better, more efficient way to move people and goods.”

Smithee has room for optimism. The engineer has seen how a project left for dead has been revived by new financial mechanisms. Not unlike the residents of Poplar Bluff, the people of Arkansas took to the polls and approved a tax. They passed a half-cent sales tax in November of 2012, set to expire this June. Then in 2020, voters approved a sequel to that tax in which $180 million was identified to put toward Future I-57 from Walnut Ridge to Missouri.

“Of course this is far from enough, as the completion is projected to be more like $400 to $600 million,” Smithee said.

A lot more work needs to be done, particularly in the way of funding. Still, based on numbers provided by Robison regarding private investments related to the U.S. 67 in the Poplar Bluff area alone, private investment along the expansion would likely far exceed public investment even at a figure of $600 million.

Regardless of the case to be made that I-57 is desired by taxpayers, that it would provide economic benefits, that it is needed to ease transportation bottlenecks, and that it is called “vital” by a U.S. Representative, no one seems to be able to project when the project might actually attach at the Missouri/Arkansas border.

When B Magazine asked if it was reasonable for the project to be finished in a decade, Smithee simply could not offer an educated guess.

“For an easy question, there is no great answer,” he said.

The answer comes down to funding. He noted how the project has pushed forward, mile by mile. In 2009, Arkansas opened a widened section of U.S. 67 from Highway 18 in Newport, Arkansas, to Highway 226. In 2016, the state opened a section from Highway 226 to Hoxie, Arkansas. Several miles were extended, but that took seven years. At one point in the 1990s, he said, he didn’t think the project would ever move forward, but “along came funding mechanisms like ARRA (American Recovery and Reinvestment Act) and TIGER (Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery).” To Smithee, mile-by-mile progress means the project is getting done, even if not at the desired speed.

Ultimately, Smithee and Robison say the future of Interstate 57 is in the hands of the federal government.

U.S. Rep. Jason Smith’s office issued a statement to B Magazine that stated, “Getting the future I-57 corridor completed is one of my top priorities when it comes to improving and modernizing infrastructure in Missouri’s 8th Congressional District. … In Congress, I’m fighting to make sure the federal government does its part in helping our state complete this vital infrastructure project. This is a top priority for so many farmers, workers, small businesses and local officials in Southeast Missouri, and I will continue working to get this project across the finish line.”

When pressed more on the potential timing that funding for the project might be secured, Smith’s office did not elaborate.

All parties seem intent on making the project happen. Rep. Smith, for example, was instrumental in getting the U.S. 60 corridor in Southeast Missouri classified as “Future I-57.” Arkansas has sealed the same classification on its side.

How quickly I-57 is completed all depends on members of Congress and the President of the United States getting on the same page to provide the national funding needed.

Unfortunately, Bill Robison doesn’t have a map for that.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.