Percival Everett and Jason De León win National Book Awards

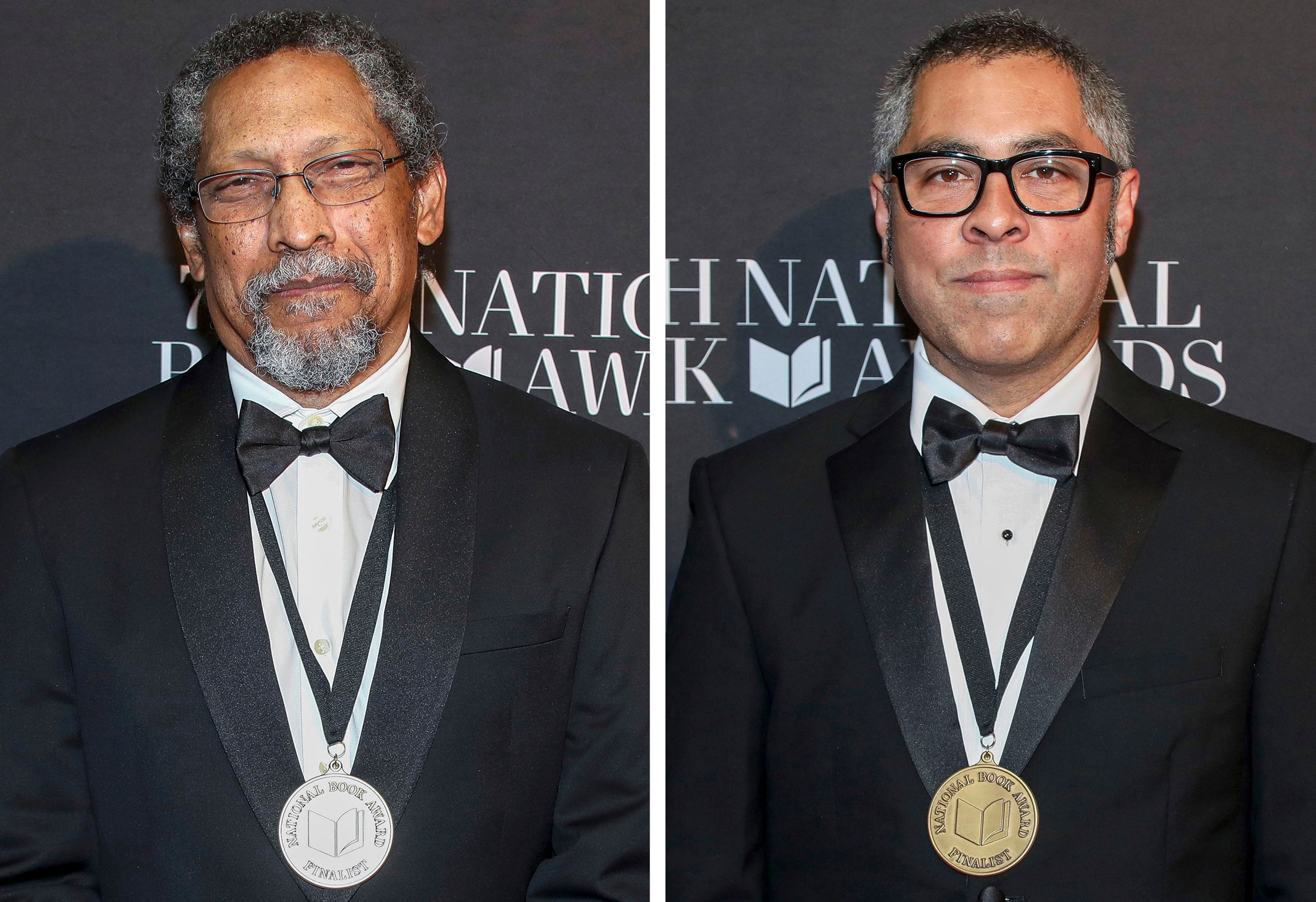

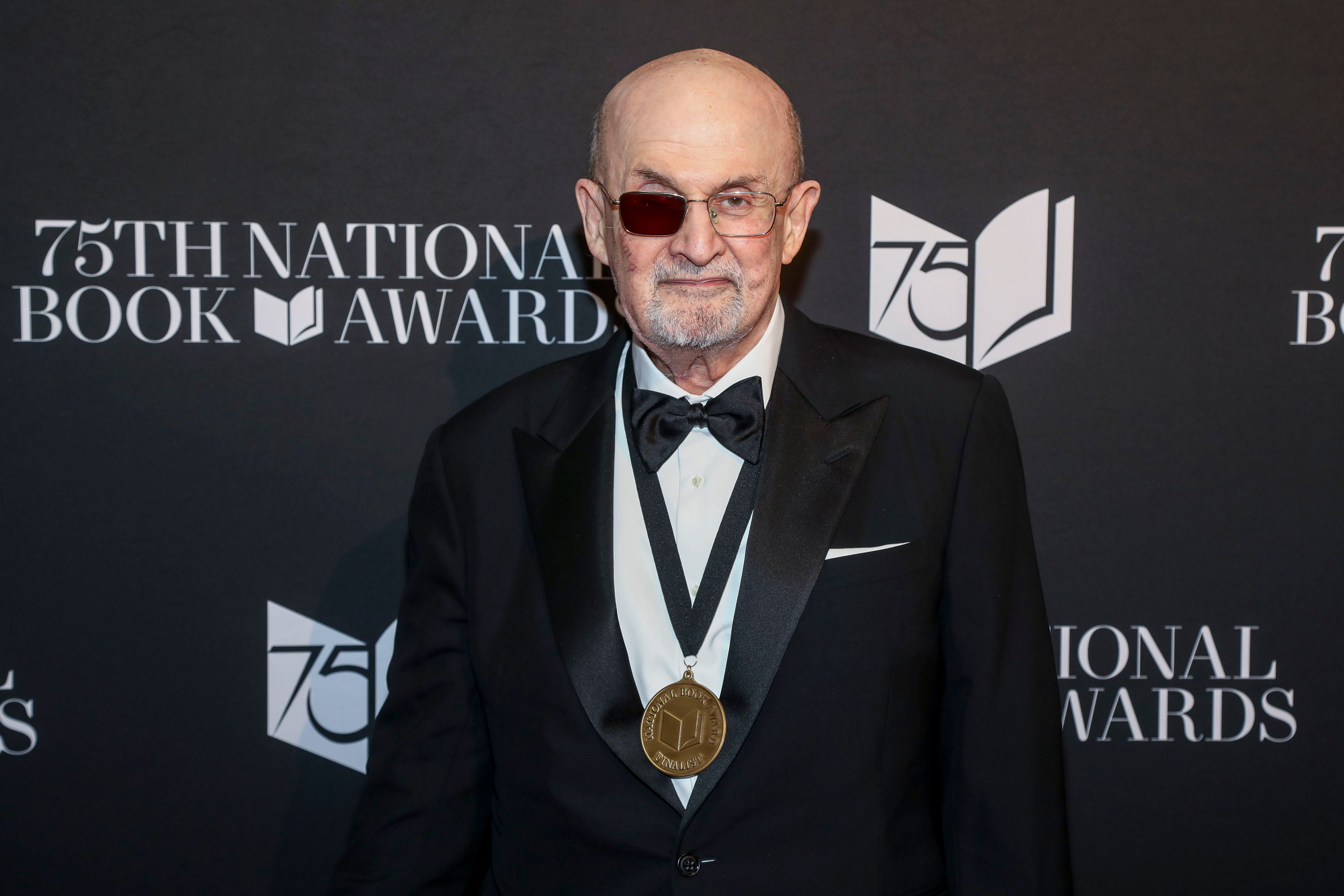

NEW YORK (AP) — Percival Everett's “James,” a daring reworking of “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” has won the National Book Award for fiction. Jason De León’s “Soldiers and Kings: Survival and Hope in the World of Human Smuggling” won for nonfiction, where finalists included Salman Rushdie's memoir about his brutal stabbing in 2022, “Knife.”

NEW YORK (AP) — Percival Everett's “James,” a daring reworking of “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” has won the National Book Award for fiction. Jason De León’s “Soldiers and Kings: Survival and Hope in the World of Human Smuggling” won for nonfiction, where finalists included Salman Rushdie's memoir about his brutal stabbing in 2022, “Knife.”

The prize for young people's literature was given Wednesday night to Shifa Saltagi Safadi’s coming of age story “Kareem Between,” and the poetry award went to Lena Khalaf Tuffaha’s “Something About Living.” In the translation category, the winner was Yáng Shuāng-zǐ’s “Taiwan Travelogue,” translated from the Mandarin Chinese by Lin King.

Judging panels, made up of writers, critics, booksellers and others in the literary community, made their selections from hundreds of submissions, with publishers nominating more than 1,900 books in all. Each of the winners in the five competitive categories received $10,000.

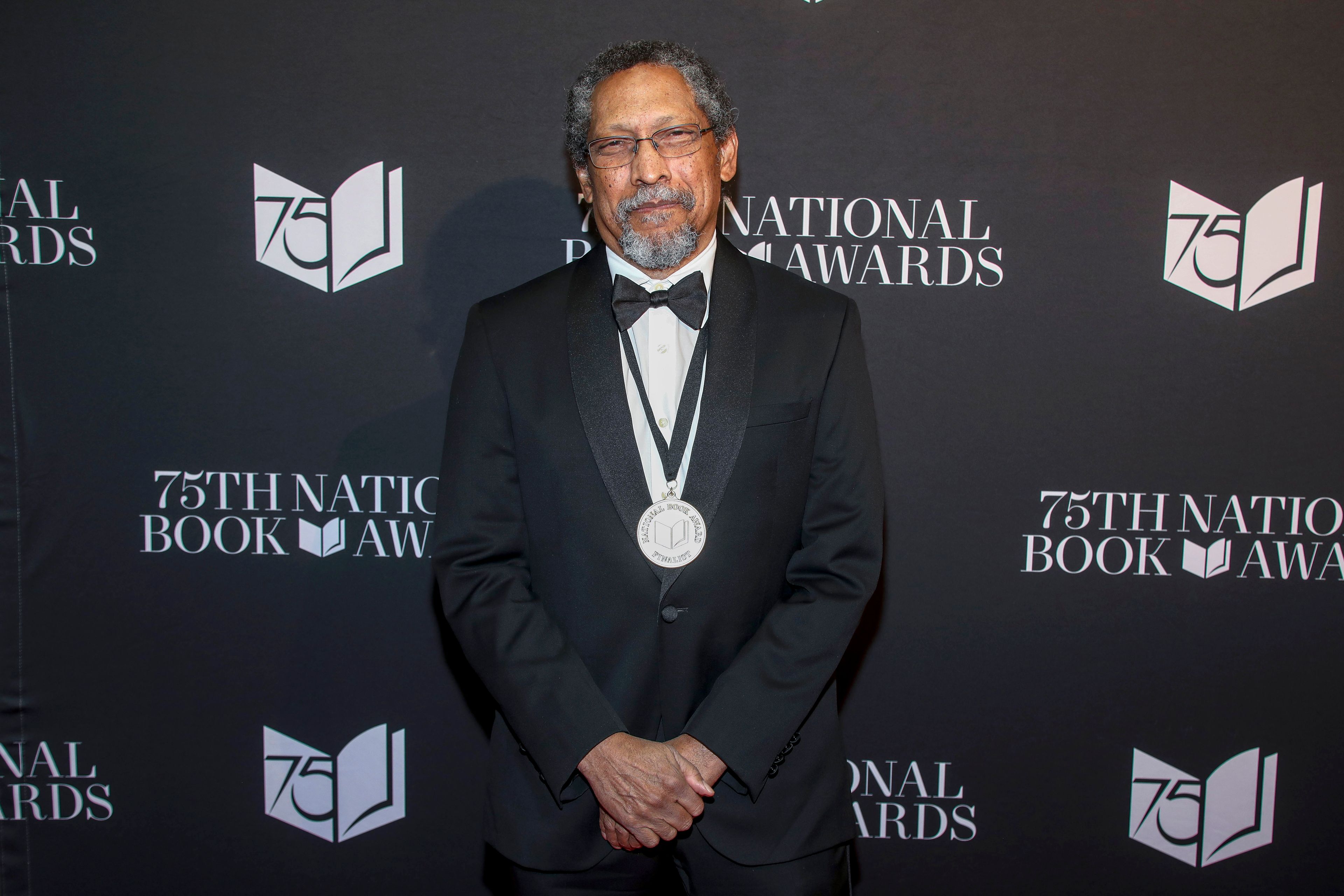

Everett’s win continues his remarkable rise in the past few years. Little known to general readers for decades, the 67-year-old has been a Booker Prize and Pulitzer Prize finalist for such novels as “Trees” and “Dr. No” and has seen the novel “Erasure” adapted into the Oscar-nominated “American Fiction.”

In taking on Mark Twain’s classic about the wayward Southern boy Huck and the enslaved Jim, Everett tells the story from the latter's perspective and emphasizes how differently Jim behaves and even speaks when whites are not around. The novel was a Booker finalist and last month won the Kirkus Prize for fiction.

“James” has been nicely received,” Everett noted during his acceptance speech.

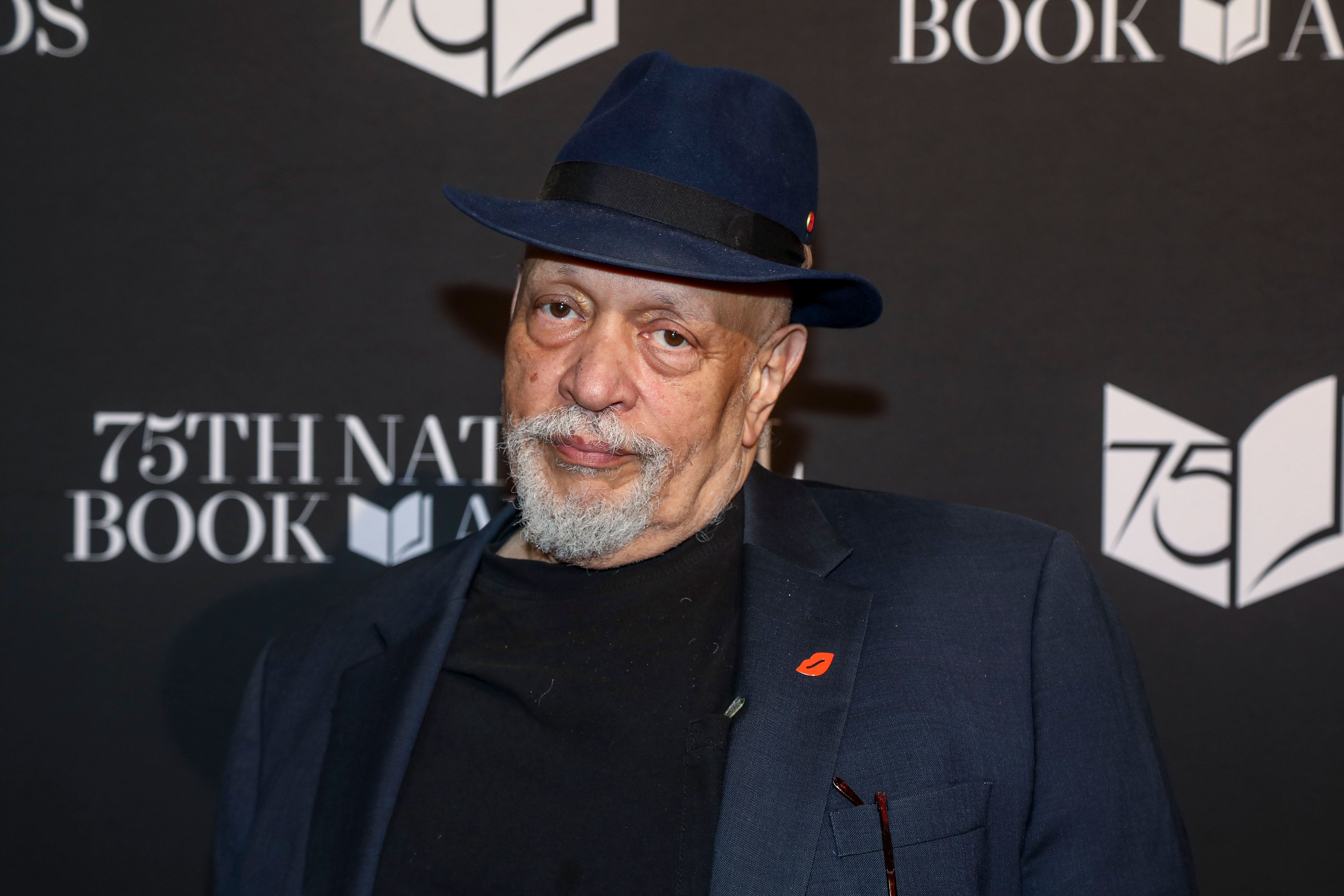

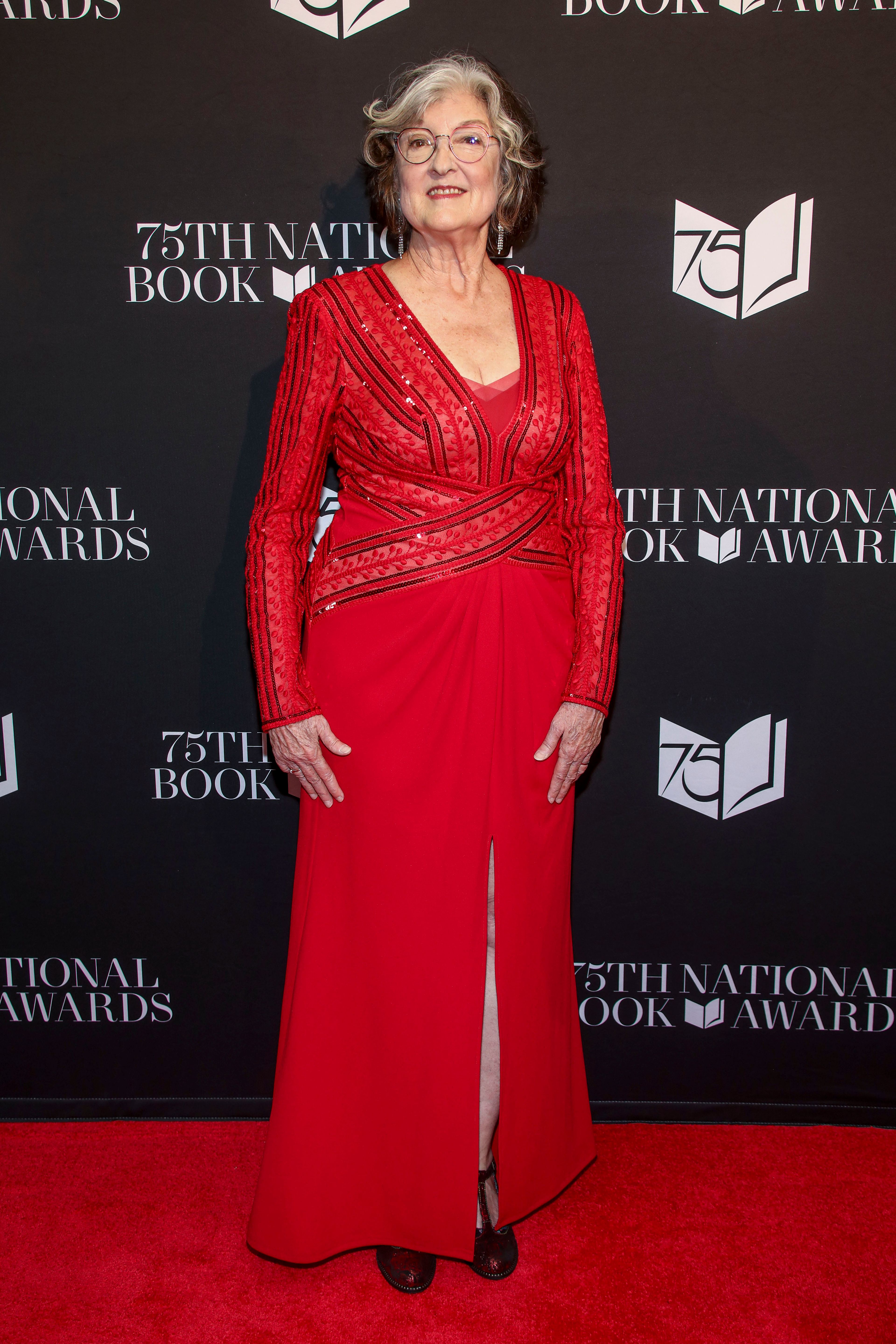

“Demon Copperhead” novelist Barbara Kingsolver and Black Classic Press publisher W. Paul Coates received lifetime achievement medals from the National Book Foundation, which presents the awards.

Speakers praised diversity, disruption and autonomy, whether Taiwanese independence or the rights of immigrants in the U.S. Two winners, Safadi and Tuffaha, condemned the year-old Gaza war and U.S. military support for Israel. Neither mentioned Israel by name, but both called the conflict “genocide” and were met with cheers — and more subdued responses — after calling for support of the Palestinians.

Tuffaha, who is Palestinian American, dedicated her award in part to “to all the deeply beautiful Palestinians that this world has lost and all those miraculous ones who endured, waiting for us, waiting for us to wake up.”

Last year publisher Zibby Owens withdrew support for the awards after hearing that finalists were planning to condemn the Gaza war. This year the World Jewish Congress was among those criticizing Coates’ award, citing in part his reissue of the essay “The Jewish Onslaught,” which has been called anti-Semitic.

National Book Foundation Executive Director Ruth Dickey said in a recent statement that Coates was being honored for a body of work rather than any individual book, and added that while the foundation condemns anti-Semitism and other forms of bigotry, it also believes in free expression.

“Anyone examining the work of any publisher, over the course of almost five decades, will find individual works or opinions with which they disagree or find offensive,” she added.

The National Book Awards have long taken place in mid-November, shortly after the elections, and they're an early snapshot of the book world's reaction: Hopeful after Barack Obama's victory in 2008, when publisher and honorary winner Barney Rosset anticipated “a new and uplifting agenda”; grim but determined in 2016, after Donald Trump's first victory, with fiction winner Colson Whitehead urging the audience to “be kind to everybody, make art, and fight the power.”

This year, as hundreds gathered for the dinner ceremony at Cipriani Wall Street in downtown Manhattan for the awards' 75th anniversary, the mood was one of sobriety, resolve and willed good cheer.

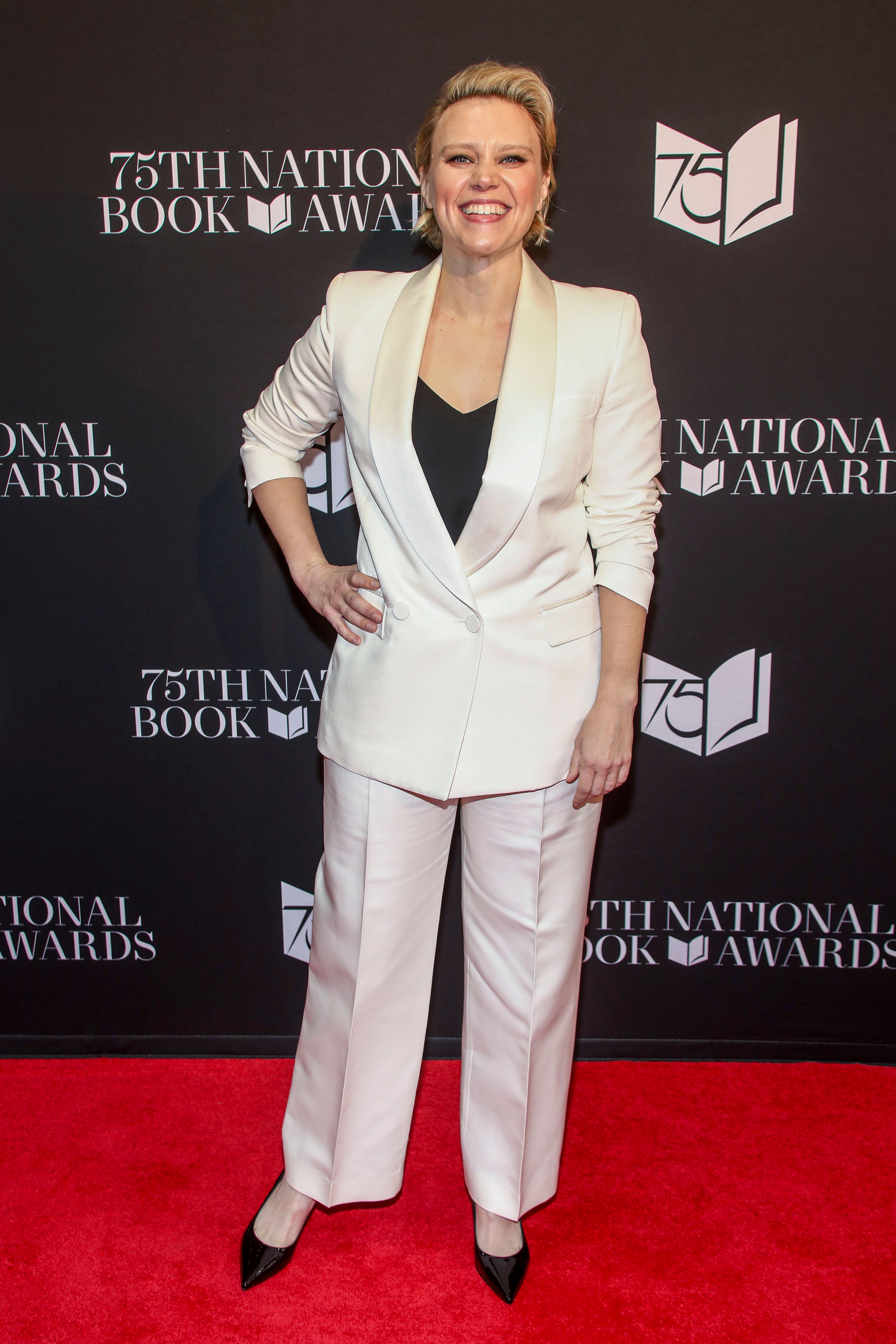

Host Kate McKinnon joked that she was recruited because the National Book Foundation wanted “something fun and light and to distract from the fact that the world is a bonfire.” Musical guest Jon Batiste led the audience in a round of “When the Saints Go Marching In” and sang a few lines from “Hallelujah,” the Leonard Cohen standard which McKinnon somberly performed at the start of the first “Saturday Night Live” after the 2016 election.

Kingsolver acknowledged feeling “smacked down, at the moment,” but added that she has known despair before. She likened truth and love to forces of nature, like gravity and the sun, always there whether you see them or not. The writer's job is to imagine “a better ending than the one we've been given," she said.

At a Tuesday night reading by awards finalists, some spoke of community and support. Everett began his turn by confiding that he really “needed this kind of inspiration after the last couple of weeks. We kind of need each other right now.” After warning that “hope is not a strategy,” he paused and said, “Never had a situation felt so absurd, surreal and ridiculous.”

It took a moment to realize he wasn't discussing current events, but rather reading from “James.”

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.