AP photos of the year: Through photographers' lenses, a catalog of humanity in 2024 emerges

Explore the power of photography in 2024 as AP photographers capture humanity's triumphs and tragedies, freezing moments from global events to intimate encounters, shaping our understanding of the world.

She was born on the water — on a boat along the River Bhramaputra in northeastern India on July 3, one of more than 100 million babies to arrive during a convulsive year. Her first tears in this world were frozen in time, available to countless faraway eyes for one simple reason: a photographer was there to bear witness.

At every speed and in every imaginable color and flavor, life in 2024 hurtled directly at us — dizzying, unremitting, challenging the human race to make sense of it. And behind it all, the unspoken questions:

How do you stop time? How do you preserve moments? Amid all the quick cuts that cut to the quick, how do you absorb what needs to be seen and remembered?

The answer is encapsulated — as it has been for nearly two centuries — in one word that contains multitudes and possibilities: photography.

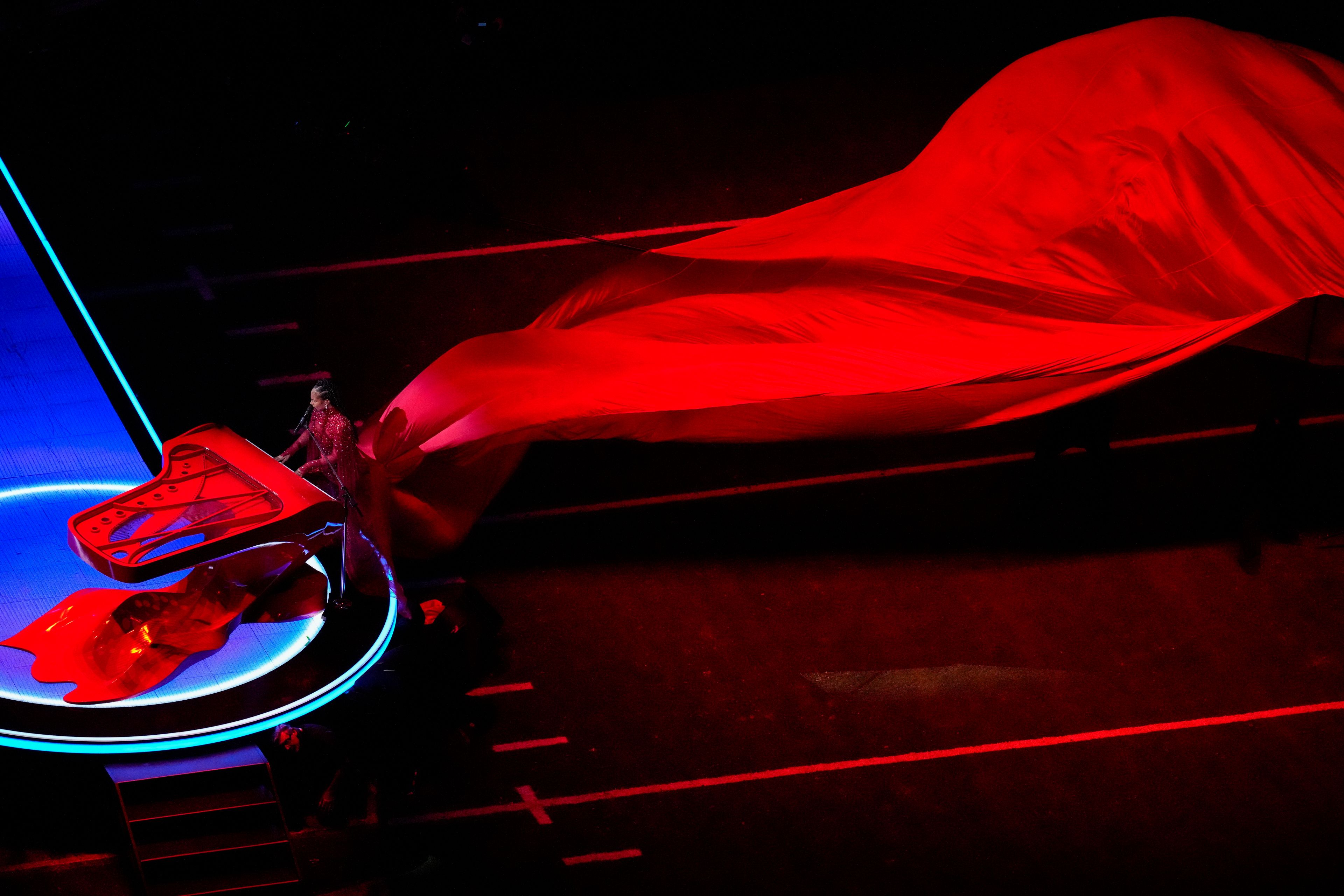

This year, Associated Press photographers across the world captured 2024’s vast catalogue of events, from breaking news (wars, natural disasters, an assassination attempt) to intimate moments both quiet (a lone fisherman in Lebanon) and exuberant (a young couple lying in a pool of squashed tomatoes at a festival in Spain).

In doing so, they assembled a visual catalog of our civilization.

Through their lenses, from the widest of wide angles to the most formidable of zooms, we saw:

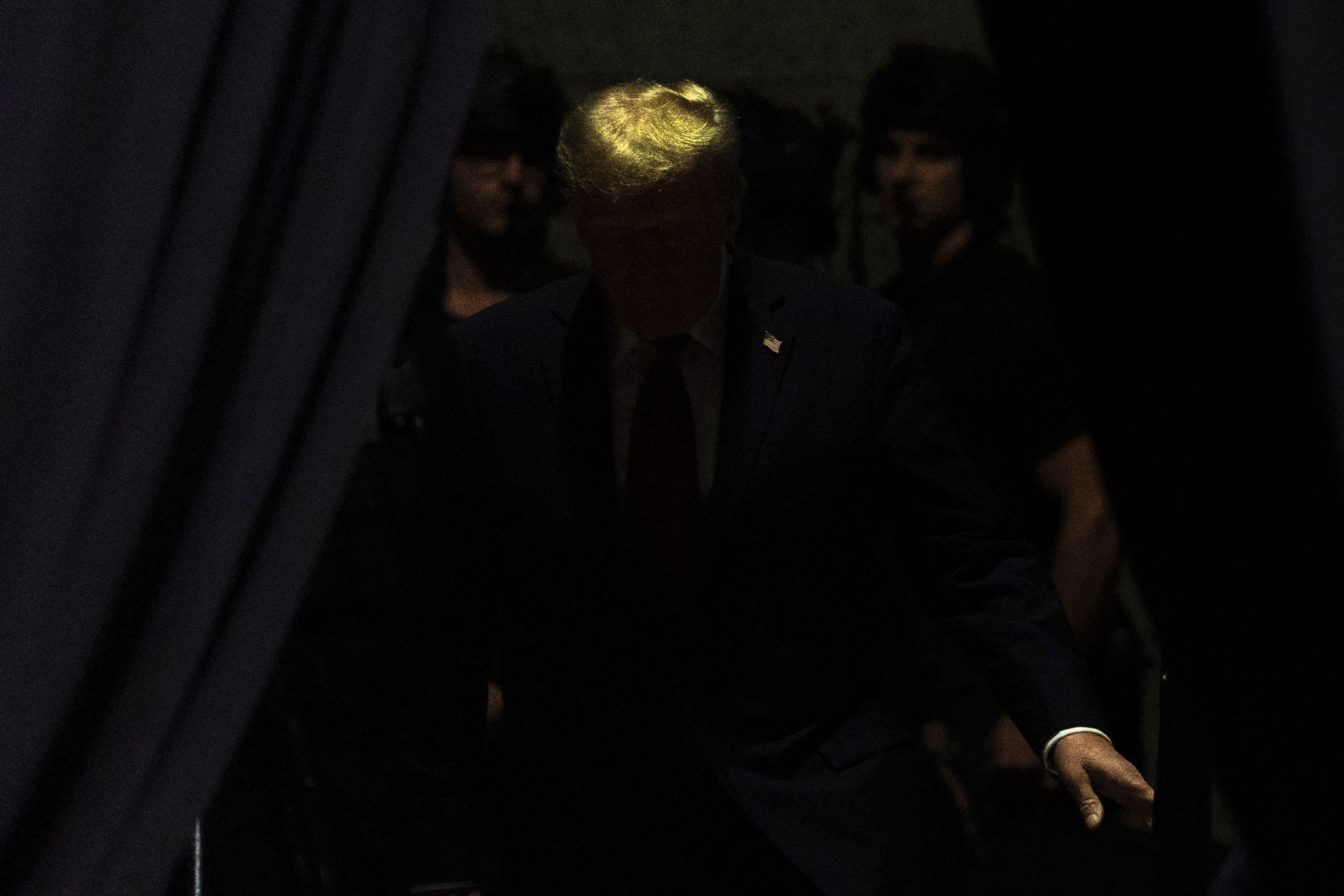

A pope alone in his chair, contemplating. Lava flowing across a burning landscape in Iceland. A former president of the United States — now its next president, too — thrusting his fist skyward in defiance after narrowly escaping an assassination attempt outside a small western Pennsylvania city.

We saw prisoners reaching out from their cells for bread at a Paraguayan prison in July — their outstretched hands grasping, hoping for something to come their way.

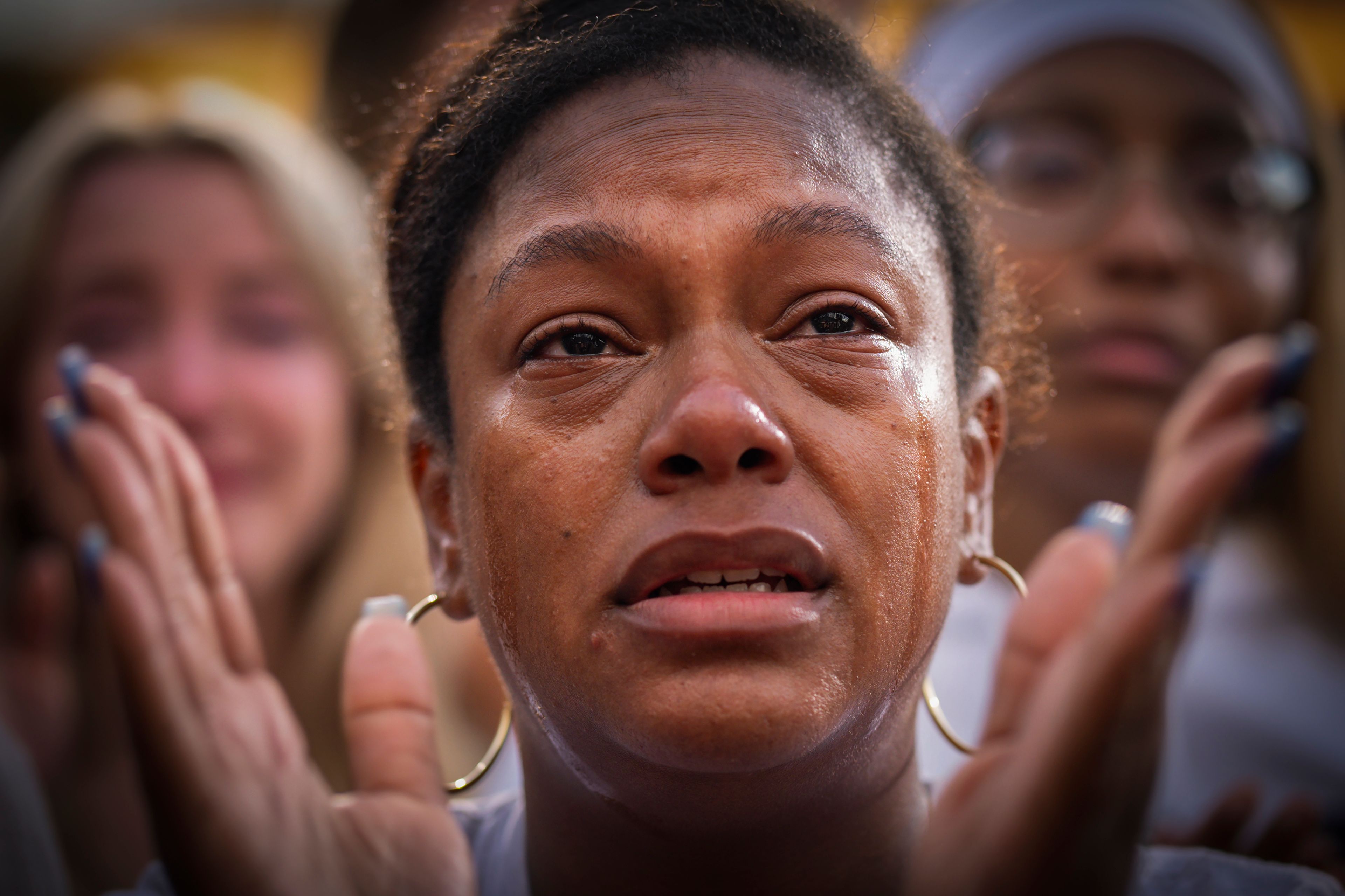

Thanks to photographers and their cameras, we were lifted by proxy into the air to look down. We were able to crawl on the ground and look up at events unfolding. We were able to gaze from a distance and to get right in front of fascinating faces.

We looked straight on. We stared at the news from oblique angles. We saw entire landscapes of violence and of inspiration, and we saw intimate detail that only a modern digital camera with a talented human being behind it can deliver.

We saw how people across the planet elected each other, loved each other, broke bread with each other, competed against each other in the most prestigious of forums. We saw them pray for — and with — each other, kill each other, mourn each other.

In these images, people fight heat, battle cold, grapple with drought, take to the sea, pass the baton, cast the fishing line, beat each other with sticks. Anxiously and expectantly, they look for better lives; sometimes, they find them.

Through the lens, time stopped for a fraction of a second on Feb. 11 when Taylor Swift kissed Travis Kelce after his team, the Kansas City Chiefs, won the Super Bowl. It stopped on Sept. 2 when Santos Araujo, an athlete with no arms, exulted in a victory in the Paralympic pool. It stopped on Aug. 28 when Faten Mreish held the body of her son, who was killed in an Israeli bombardment of the Gaza Strip. It stopped to show a rainbow presiding over an Olympic training session in Tahiti.

In photography, vantage point is everything. Where the camera goes is what we see. The choices that AP photographers make in mere seconds can shape how we see our world for years. Flip through these photos in that light, and they become even more impactful.

Consider the case of Christophe Chavilinga, a 90-year-old man from a camp for displaced people called Munigi in eastern Congo. This year, he fell sick with mpox. By Aug. 16, the blistering lesions from it covered much of his face.

That was the day that, while he waited to be treated at a clinic, he stared straight into a camera. His eyes were weary. His mouth drooped. His dignity came through in every pixel. And that moment, frozen, was beamed around the world.

How do we stop time in 2024? A photographer reaches the scene, presses a button. A sophisticated contraption reacts to light. Pixels are preserved, edited and transmitted across the world. And in the process, time doesn’t merely stop.

Somehow, each image manages to stop the world just a little. It manages to give us snippets of time to think about those around us and those far from us — and how they, like so many, are muddling their way through the 21st century, trying to survive and prosper. Some succeed, some do not.

But at its best, photography introduces us to them. It takes us to them, and brings them home to us.

___

Ted Anthony, director of new storytelling and newsroom innovation for The Associated Press, writes frequently about photography. Follow him at http://x.com/anthonyted

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.