The ability to cast a ballot isn’t always guaranteed in Alaska’s far-flung Native villages

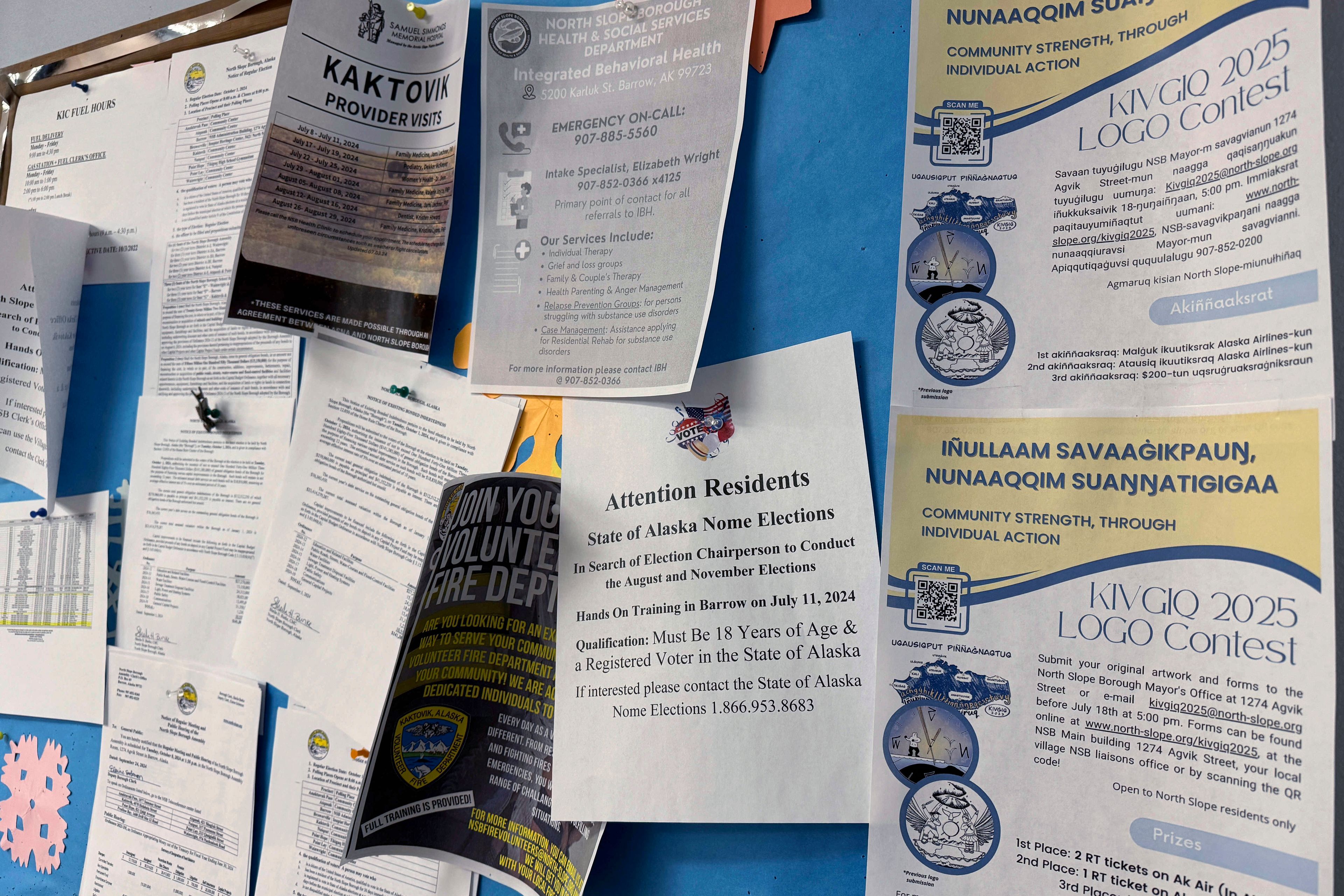

KAKTOVIK, Alaska (AP) — Early last summer, George Kaleak, a whaling captain in the tiny Alaska Native village of Kaktovik, on an island in the Arctic Ocean just off the state’s northern coast, pinned a flyer to the blue, ribbon-lined bulletin board in the community center.

KAKTOVIK, Alaska (AP) — Early last summer, George Kaleak, a whaling captain in the tiny Alaska Native village of Kaktovik, on an island in the Arctic Ocean just off the state’s northern coast, pinned a flyer to the blue, ribbon-lined bulletin board in the community center.

“Attention residents,” it read. “In search of elections chairperson to conduct the August and November elections. … If interested please contact the State of Alaska Nome Elections.”

No one was interested, Kaleak said, and the state failed to provide an elections supervisor or poll workers.

When the primary arrived on Aug. 20, Kaktovik’s polling station didn't open. There was nowhere for the village’s 189 registered voters to cast a ballot. Kaleak, who also is an adviser to the regional government, didn’t even try.

“I knew there was nobody to open it,” he said during an interview in Kaktovik earlier this month.

The development might have shocked voters or politicians elsewhere in the U.S., especially in swing states where any polling irregularities prompt scrutiny from party activists and news organizations, conspiracy theories spreading on social media and calls for investigations.

In Kaktovik, life went on. Some residents were frustrated, but they turned their attention to a more pressing matter: the start of whaling season.

Remote villages, few poll workers

The shuttered polling station represents just the latest example of persistent voting challenges in Alaska’s remote Native villages, a collection of more than 200 far-flung communities that dot the nation's largest state. Many of the villages are far from the main road system, so isolated they are reachable only by small plane. Mail service can be halted for days at a time due to severe weather or worker illness.

Polling sites also did not open for the August primary in Wales, in far western Alaska along the Bering Strait. They opened late in several other villages. In Anaktuvuk Pass, the polling place didn’t open until about 30 minutes before closing time; just seven of 258 registered voters there cast ballots in person.

This year, with control of Congress on the line, the implications of any repeated problems during the November general election could be enormous. The state’s only representative in the House is Democratic Rep. Mary Peltola — the first Alaska Native to serve in Congress. She is popular among Alaska Native voters, won the recent endorsement of the Alaska Federation of Natives and is in a tight reelection fight against Republican Nick Begich.

“This congressional seat is going to be won by dozens of votes,” Peltola told a federation convention this month.

State, regional and local officials all say they are trying to ensure everyone can vote in the Nov. 5 election. In a written statement, Carol Beecher, director of the Alaska Division of Elections, called her agency “highly invested in ensuring that all precincts have workers and that sites open on time.” She acknowledged it can be difficult to find temporary workers to help run elections.

‘Out of sight and out of mind’

Like other Indigenous populations across the U.S., Alaska Native voters for years faced language barriers at the polls. In 2020, the state Division of Elections failed to send absentee ballots to the southwest Alaska village of Mertarvik in time for the primary election because its staff didn't realize anyone was living there.

In June 2022, a special primary for the U.S. House was conducted primarily by mail after the sudden death of Republican U.S. Rep. Don Young. Some rural Alaska and lower-income urban districts had notably high rates of ballots disallowed — around 17% — due largely to missing witness signatures on envelopes or other mistakes the state provides no means of correcting.

Two months later, precinct locations in two southwest Alaska villages — Tununak and Atmautluak — did not open for the regular primary and special general election for the U.S. House, which were held on the same day. Ballots from several other villages arrived too late to be fully tabulated under the new ranked choice voting system the state uses for general elections.

“When these things happen in rural Alaska, when it’s out of sight and out of mind, it seems like the system just shrugs and writes it off as a character flaw for remote Alaskans," said Michelle Sparck, with the nonprofit Get Out The Native Vote. “And we’re here saying this is unacceptable.”

Alaska allows absentee voting, but that can present its own challenges, given the sometimes questionable reliability of mail delivery in rural Alaska.

The Alaska Federation of Natives, the largest statewide Native organization in Alaska, passed a resolution last year raising concerns with mail service. It is surveying residents about their postal service, including how it affects their ability to vote or obtain medicine.

A land of caribou, whales and polar bears

Kaktovik is 670 miles (1,078 km) north of Anchorage, on Barter Island, between the Arctic Ocean and Alaska's North Slope, an area of vast, treeless tundra nearly the size of Oregon. The temperature can dip to 20 below zero F (29 below C) during the perpetual darkness of winter. Air travel provides the only year-round access to Kaktovik, with ocean-going barges delivering goods in the warmer months.

It’s the only community in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, and whether the next presidential administration will support drilling for oil in the refuge — as many villagers hope — is a major topic of concern. The nearest settlement is Deadhorse, about 110 miles (177 kilometers) west, the oil company supply stop that marks the end of the gravel road featured in the reality TV show “Ice Road Truckers.”

Kaktovik's roughly 270 residents, mostly Inupiat, live in single-story houses laid out in a grid of about 20 blocks. They subsist by hunting caribou and bowhead whales; village whalers landed three bowheads this year.

After butchering the whales on a nearby beach, the villagers pile the bones farther away, where polar bears feast on the scraps. That’s made Kaktovik a popular spot for polar bear tourism. The village also has a polar bear patrol, led by village mayor Nathan Gordon Jr., to run the animals out of town when they get too close.

During the August primary, some residents were away hunting or fishing. The mayor was on vacation with his family in Anchorage.

Plenty of obstacles to staffing polling sites

Madeline Gordon, a former election worker, had taken a new job at a village grocery store. Gordon, the mayor's cousin, said she told the Nome office of the state elections division in early summer that she wouldn’t be able to run the primary election, but the state nevertheless mailed a box of ballots to her home.

She gave the box to a city clerk, Tiffani Kayotuk. A state official told Kayotuk to hang onto it until further notice, Kayotuk said. The box was still in her office when she went on maternity leave on the day of the primary.

It had been clear well before then that Kaktovik would need help running the primary.

Kaleak, a deputy adviser to the top official of the regional North Slope Borough — equivalent to a county government in other states — posted the flyer seeking help staffing the election on the community center bulletin board. It was still hanging there recently, near one for the volunteer fire department and another for the local fuel depot. He also posted notices on a community Facebook page.

But the position required travel to Utqiagvik, formerly known as Barrow, for training. And, Kaleak said, the pay — $20.50 an hour — wasn’t enough to be attractive in a village where gas is $7.50 a gallon and other goods, shipped long distance, are similarly pricey. Small pumpkins were going for $80 apiece this month.

Taylor Thompson, who heads the legal department for North Slope Borough, said a borough official had reached out to the state elections division before the August primary to find out if they anticipated problems, and offered to fly a borough staffer to the village if needed.

“The state just didn’t take us up on it,” Thompson said.

She said she “lost it” when she learned from a news article that Kaktovik's precinct hadn't opened. This time, the borough is sending a worker to Kaktovik to ensure the precinct opens for the general election.

“We’re going to make sure that someone is there, no matter what, if the state’s not going to fulfill their obligations,” Thompson said.

Determined to ensure voters won't be disenfranchised again

The borough also was trying to coordinate with the state to ensure polls will be staffed in two other villages, Nuiqsut and Anaktuvuk Pass.

Beecher, the elections division director, said the state was notified late on the afternoon before the primary that Kaktovik didn’t have anyone to run the polls. The division immediately reached out to the village and the borough in hopes of finding someone, she said.

“Unfortunately, despite best efforts, sometimes the trained staff are no longer available, requiring the division to secure other workers and get them trained in a short timeframe,” Beecher said.

The mayor said he got an earful when he returned from vacation.

“I end up coming back and hearing about how the primary wasn’t opened and how people had to miss their first-ever election,” Gordon Jr. said.

Charles Lampe, the president of the Kaktovik Inupiat Corp. and a city council member, favors getting city officials trained to work elections. That way, he said, “nothing like this ever happens again."

For Kaleak, the disenfranchisement of Alaska Native voters should raise as much outrage as the disenfranchisement of voters anywhere else in the country.

“Every person should be able to have a vote, and it should count, and it should be fair,” he said.

___

Bohrer reported from Juneau, Alaska. Johnson reported from Seattle.

___

The Associated Press receives support from several private foundations to enhance its explanatory coverage of elections and democracy. See more about AP’s democracy initiative here. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.