‘US doesn’t see me as an American’: Thousands of adoptees live in limbo without citizenship

HENDERSON, Nev. (AP) — The 50-year-old newspaper was turning yellow and its edges fraying, so she had it laminated, not as a memento but as proof — America made a promise to her, and did not keep it.

HENDERSON, Nev. (AP) — The 50-year-old newspaper was turning yellow and its edges fraying, so she had it laminated, not as a memento but as proof — America made a promise to her, and did not keep it.

She pointed to the picture in the corner of her as a little girl in the rural Midwest, hugging the family Yorkshire terrier, with dark pigtails and brown eyes so round people called her Buttons. Next to her sit smiling, proud parents — her father an Air Force veteran who had survived a German prison camp in World War II and found her in an orphanage in Iran. She was a skinny, sickly 2-year-old; he and his wife decided in 1972 to take her home and make her their American daughter.

They brought her to the United States on a tourist visa, which in the eyes of the government she soon overstayed as a toddler — and that is an offense that cannot be rectified. She is one of thousands of children adopted from abroad by American parents — many of them military service members — who were left without citizenship by loopholes in American law that Congress has been aware of for decades, yet remains unwilling to fix.

She is technically living here illegally, and eligible for deportation.

“My dad died thinking, ‘I raised my daughter. I did my part,’ but not knowing it put me on a path of instability and fear,” she said. The Associated Press is using only her childhood nickname, Buttons, because of her legal status. “Adoption tells you: You’re an American, this is your home. But the United States doesn’t see me as an American.”

Every time she turns on the news, she hears former President Donald Trump, in his bid for reelection, promising to round up immigrants living illegally in the U.S. Now she lays awake at night, wondering what it would be like to be sent back to Iran.

“What is a detention camp even like?” she wondered.

“We have a plan, we won’t let that happen,” her friend Joy Alessi, a Korean adoptee, assured her. They have lawyers, media statemetns prepared, phone numbers of sympathetic congressmembers.

But they slumped their shoulders — they know it could happen, because it already has.

Out of the shadows

These two women grew up in military families, and were taught to be grateful to the nation that celebrated saving them. Then one day, as adults, they walked into passport offices and learned the news that would unspool their lives.

Their adoption paperwork, signed by judges and stamped by governments, declared they enjoyed all the privileges of being daughters of American families. But that was untrue in one critical respect: Adoption for decades did not automatically make children citizens.

They both hid for years, thinking they were the only one who fell through the cracks. Then Trump stormed into politics in 2015 on a promise to rid America of undocumented immigrants. They weren’t citizens, so they couldn’t even vote to try to stop him. Each decided they had nothing left to lose, emerged and found each other.

Other adoptees found them, too, and told stories of indignities endured by those not fully American — they can’t get jobs or driver’s licenses or passports, every interaction with the government is terrifying, some panic when there’s a knock on the door.

No one knows how many of them there are — estimates range from 15,000 to 75,000. Many were adopted from South Korea, home to the world’s longest and largest adoption program, but they’d also been brought from Ethiopia, Romania, Belize, more than two dozen countries.

They started the Adoptee Rights Campaign, and were joined by an unexpected coalition, from the Southern Baptist Convention to liberal immigration advocates, all baffled that the government let this linger.

The Adoptee Rights Campaign has heard from people who’d been deported, some still living in hiding, others freshly discovering they’d never been made citizens. There is no government mechanism for alerting them. They find out by accident, when applying for passports or government benefits. One woman learned as a senior citizen, when she was denied the Social Security she’d paid into all her life.

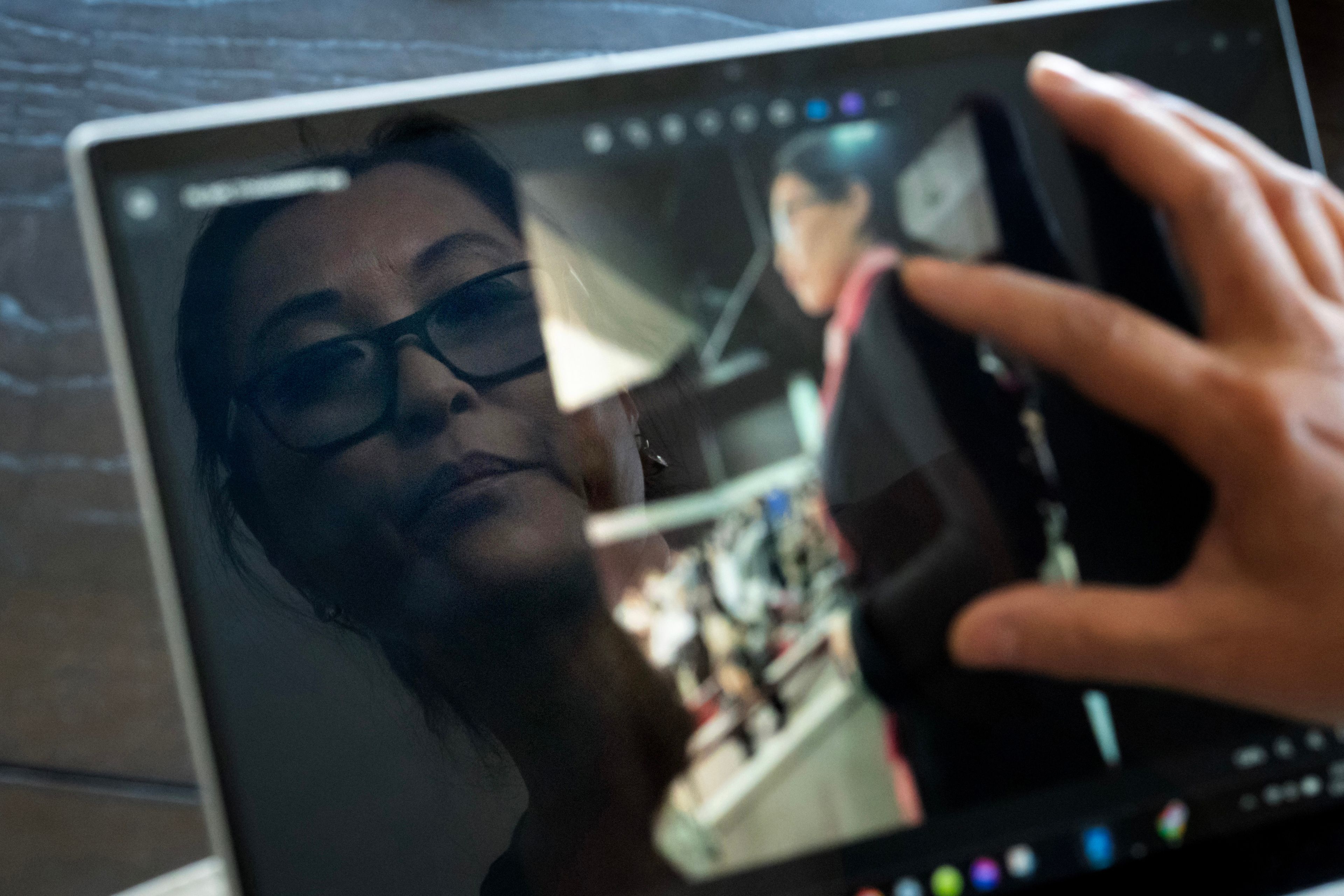

Buttons calls herself the group’s “adoptee wrangler;” she was visiting Alessi in Nevada, sitting at her kitchen table, fielding inquiries and checking in on people.

She’s 54 and has never been in trouble; she has a corporate job in health care, owns her own home in California. She was raised a Christian, so fears that deportation to Iran would be “a death sentence.” Still legislators won’t help.

She had hope. She’s lost that now. For a decade, legislation has been introduced over and over, it dies, and nothing happens.

So she lugs around the laminated newspaper clipping, stacks of adoption files and court records as proof she’s supposed to be here.

“It’s hard to give hope,” she said, “when I don’t feel like I have any left.”

‘One piece of paper can ruin your life’

Alessi anointed her friend Buttons “an honorary Korean.”

This problem they have both endured was born there, in Alessi’s motherland, and to her it represents the most glaring example of the neglectful system that brought them here.

The international adoption industry grew out of the wreckage of the Korean War in the 1950s. Americans were desperate for babies — the domestic supply of adoptable children had plummeted — and South Korea wanted to rid itself of mouths of feed. Alessi was among this early wave of adoptees, taken from South Korea at 7 months old in 1967.

The system focused on shipping children abroad as quickly as possible. Korea’s government, eager to curry favor with the U.S., did everything it could to speed up the process, including relaxing the obligation of agencies to ensure citizenship for adoptees.

The adoption industry took the model created in South Korea into poor countries around the world, shipping babies in bulk to American families.

South Korea has struggled to track the citizenship of children placed in U.S. homes, and the status of more than 17,550 remains unconfirmed, according to government data AP obtained. The Adoptee Rights Campaign used Korean figures to estimate up to 75,000 adoptees from all over the world could lack citizenship. But groups like the National Council for Adoption put the number somewhere between 15,000 and 18,000.

The Korean adoption diaspora has been hit particularly hard — there are simply more of them. At least 11 adoptees have been deported to South Korea since 2002, where they don’t know the language or the culture. An adoptee named Phillip Clay, sent to the U.S. at 8 years old in 1983, was deported. He killed himself by jumping from an apartment building in Seoul in 2017 at 42 years old.

Adam Crapser, adopted at 3 years old in 1979, was also deported to South Korea. The married father of two says he was abused and abandoned by two different adoptive families who never filed his citizenship papers. He got into trouble with the law — once for breaking into his adoptive parents’ home to retrieve the Bible that came with him from the orphanage.

He sued his Korean adoption agency, Holt Children’s Services, and a court last year ordered the agency to pay him damages for failing to inform his adopters that they should take steps to secure his citizenship.

For some adoptees, their status is fixable through the arduous naturalization process — they have to join the line as though they’d just arrived. It takes years, thousands of dollars, wasted days, routine rejections from immigration offices on technicalities, the wrong form, an errant typo.

Alessi looked at a picture of herself standing in a high school gymnasium, finally being made an American citizen at 52. “We welcome you!” she remembers the announcer saying, and the crowd cheered. But her body looks stiff, her mouth pursed.

“You don’t welcome us,” she thought that day in 2019.

Her friend, the adoptee called Buttons, was at the ceremony crying, genuinely happy for her friend, but also devastated for herself. Alessi felt a sort of survivor’s guilt.

“You were sitting right there, and I felt so conflicted, so shameful,” Alessi told her.

Because for some adoptees, there is no clear solution. The difference between them is what visa their adoptive parents brought them in on, and many chose the fastest route — like a tourist or medical visa — not imagining complications down the road.

“One piece of paper,” Buttons said, “can ruin your life.”

‘A collective failure’

A quarter-century ago, the U.S. Congress recognized it had left adoptees in this legal limbo.

By 2000, nearly 20,000 children were coming to America each year. But the U.S. had wedged foreign adoptions into a system created for domestic ones. State courts give adopted children new birth certificates that list their adoptive parents’ names, purporting to give them all the privileges of biological children.

But state courts have no control over immigration. After the expensive, long process of adoption, parents were supposed to naturalize their adopted children, but some never did.

Those early decades of adoption were a “wild west,” said Greg Luce, a lawyer who has represented many non-citizen adoptees; there was no standardized procedure to help adoptive families.

“It’s a combination of adoption agencies that were neglectful, adoptive parents who should have known better, and the U.S. government that had lax oversight and a visa system that could allow this to happen,” Luce said. “It’s a collective failure on the part of everyone who was involved except the adoptee. They were a child, and they’re the ones left holding the bag.”

The U.S. is unique in this: No other nation that has taken in adopted children deprives them of citizenship.

In 2000, Congress acknowledged that injustice and passed the Child Citizenship Act, conferring automatic citizenship to adopted children. But it was designed to streamline the process for adoptive parents, not to help adoptees, and so applied only to those younger than 18 when it took effect. Everyone born before the arbitrary date of Feb. 27, 1983, was not included.

Hannah Daniel, director of public policy for the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, the lobbying arm of the Southern Baptist Convention, said lawmakers often find this situation hard to believe.

“I agree that it feels unbelievable,” she said. “It’s the most classic example of wanting to bang your head against the wall, because how in the world have we not fixed this?”

Adoption has been a rare issue championed by lawmakers on both sides of the aisle, a way of saving children by making them American. Many churches preach intercountry adoption as a Biblical calling.

Daniel is part of a bipartisan coalition lobbying for a decade for a bill that extends citizenship to everyone legally adopted by American parents. The groups insist that families formed by adoption are due the same respect, the same rights, as biological ones, including equal treatment under the criminal justice system.

But that argument has been consumed by the country’s hyper-partisan frenzy over immigration. Any bills offering paths to citizenship have stalled out.

Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley, among those skeptical of the legislation, declined an interview. A spokesperson wrote in a statement that he is “a longtime adoption advocate” but “believes that any adult seeking U.S. citizenship should have their criminal records taken into consideration.”

That is a sentiment that advocates of the bill say undermines the very meaning of adoption. If a foreign adopted sibling and a biological sibling commit a crime together, the biological child would pay their debt to society and move on. The adopted child might face a second, severe punishment: getting sent back to where the U.S. professed to have rescued them from.

A bill is before Congress again now. But Daniel isn’t hopeful.

“In this day and age in Congress, if not doing anything is an option,” she said, “that is the bet I’m going to take.”

‘The American dream’

Laura Lynn Davis called her representatives, her senators. She’s written to celebrities and talk show hosts, thinking surely someone would help.

Mike Davis, her husband of 27 years, was adopted by a soldier, a Vietnam veteran stationed in Ethiopia, who met him there as a boy and brought him to the U.S.

He was deported to Ethiopia two decades ago, and now lives in a room with a mud floor and running water only once a month and even when the tap works, it isn’t safe to drink.

Davis, now 61, remembers his father telling him that everything would be OK because he was an American now. He pledged allegiance to the flag every morning and considered himself a happy military brat, moving around Army bases.

“I was living the American dream,” Davis said.

He worked at a pizza shop through high school and when he graduated, he opened his own.

In the 1990s, he was charged with possession of a firearm, marijuana and cocaine. He didn’t go to prison; he was sentenced to 120 days in a boot camp program. He found out he’d never been naturalized when he reported to his probation officer.

Nothing happened for years. He married Laura Lynn, they had children to raise, and he pushed it to the back of his mind.

Then one day in 2003, he closed his pizza shop and went to bed, someone banged on their door at 5 a.m.

“My kids were sleeping,” he said, “When they woke up, their dad was gone.”

He languished in a detention center for over a year, terrified, because he had the same perception of Ethiopia as every American: The State Department advises its citizens to not go there because of unpredictable violence, kidnappings, terrorism.

Then officers took him to the airport and put him on a plane, he said. One officer felt sorry for him and gave him $20; Davis promised to pay him back when he returned to the U.S.

He sold his wedding ring to pay rent, and that was the darkest moment. His adoptive father grew sicker, and Davis anguished over not being with him in the end.

His wife sold their house and moved their family to be with him. But life was hard in Ethiopia: There were people with M16s on the street, they couldn’t work or speak the language. Laura Lynn lost 30 pounds. She and their children went home to Georgia.

Mike was their breadwinner, and they struggled without him. They lived in cars and motels, but never blamed him.

Laura Lynn kept all his things neatly packed and awaiting his return: clothes, sports memorabilia, his favorite music — on cassette tapes, a reminder of how the world changed since he left. He gets sick a lot as he’s getting older, she said, and can’t access medications in Ethiopia.

He has five grandchildren he’s never met. His youngest son, Adam, 26 now, recently moved into his first apartment, and thought how nice it would be to have his father there to see it.

Laura Lynn has more hope than she has in a long time, she said, because a group she never expected came to their aid: Koreans. They’ve offered advocacy and legal help. He’s being represented by groups like Asian Americans Advancing Justice and Adoptees for Justice.

“I pray we can make them see that he didn’t ask to come here, he was adopted and brought here. He became a really good man,” she said. “He has a family who loves him and we’re ready for him to come back home to us.”

‘A spin of the roulette wheel’

Emily Howe, a lawyer in California, carries around a 5-inch binder, which she calls “the simplified version” of the labyrinthine set of laws that dictate which adoptees have been able to become citizens and which have not.

Howe was adopted from South Korea in 1984, barely young enough to be granted citizenship by the 2000 law. By a twist of luck and timing, this could have been her, she said. So she represents many adoptive families for free.

“It shouldn’t be a spin of the roulette wheel,” she said. She now asks every adoptee if they know their citizenship status. It gets complicated quickly; if they ask the government and find out they aren’t citizens, they tip off authorities to them living here illegally.

Her clients are panicking about what will happen if Trump wins reelection.

“I’m terrified,” a mother named Debbie cried in Howe’s San Diego office. “What if he gets back in? I’m hearing him talk about mass deportations.”

Debbie and her husband, Paul, adopted two special-needs children from a Romanian orphanage in the 1990s, and they’ve been trying to make them citizens almost ever since. The Associated Press is using only the first names of the parents because they fear endangering their adopted children.

The California couple watched a “20/20” television special about the plight of children there — they called them “unsalvagables,” they didn’t learn to read, there wasn’t enough food.

The couple was middle-class, with three biological children. But Debbie couldn’t sleep thinking about those kids, cold and hungry. So they refinanced their house to bring home two, a boy and a girl.

“We thought we had to get these children out of there. Then we’ll deal with what we need to deal with,” Debbie said.

The boy was 10, and so small, just 40 pounds, that the school allowed him in kindergarten. The girl was 14 and legally blind, with limited vision in just one eye. They both had physical and cognitive impairments; the doctors believed the boy suffered fetal alcohol poisoning.

The family was overwhelmed by their needs. Their new son was curious — in another life, he might have been an engineer, Debbie thinks. But in this one, they had to nail the front door shut because he’d wander out at night. He was fascinated by electricity, and couldn’t be left alone without fear he’d start a fire.

Howe assures them they did everything they could.

“We thought we did it the right way, we tried to, I hope we did,” Debbie said. “Maybe we were naive. Maybe there was something we missed.”

They consulted with dozens of lawyers, who all said it couldn’t be fixed — it was a convoluted calculation of the children’s ages, how their birth certificates were written, their visas. They can’t tally how many thousands of dollars they’ve spent.

“It’s dumb, it’s outrageously dumb, it should not be this monstrous task,” Howe said. “This could be fixed in a month if anyone had the political will to do it.”

Their son, 43, doesn’t understand the situation he’s in. But their daughter understands. She’s a Special Olympian, now 46, with a stack of gold medals. She can’t compete in international competitions because she can’t get a passport.

“I want to be a citizen really bad,” their daughter said. “I want to be here for a long, long time.”

They've called their legislators. Debbie wept again and again: “My adopted children deserve all the privileges of my birth children. They are no different in our eyes. Why are you looking at them differently?”

Everyone told them not to worry because they aren’t the type of people on immigration’s radar.

Then Trump’s administration terrified them. Debbie lay in bed, thinking her children couldn’t survive a detention camp. She imagined someone barging into their home and snatching them. It made her physically sick.

Debbie and Paul are in their late 60s, and feel an urgent need to fix this.

“The clock is ticking,” Debbie said. “I have zero regrets about adding these two to my family. But this country let them down, absolutely, without a doubt.”

‘It’s time for my country to fight for me'

For most of her life, Joy Alessi was a proud patriot, who got teary-eyed when Garth Brooks sang about America. But patriotism is confusing for her now — as it is for many of the adoptees who’ve found themselves in this predicament.

Alessi and Buttons hadn’t seen their friend and fellow adoptee, Leah Elmquist, since she became naturalized.

“Do you feel different? Do you feel like a citizen?” Alessi asked her, when they met for dinner at a Korean barbeque.

Elmquist had always considered herself “super-duper American.” She served in the Navy for 10 years; she was in a USAA commercial. That was all before she was actually made an American.

She told Alessi she doesn’t feel any differently now.

“I felt like a citizen for the decade I was in the Navy. And I wasn’t one,” she said.

Elmquist was adopted from South Korea as an infant in 1983, just six months too old to get citizenship by the 2000 legislation.

She grew up in a white family in a Nebraska town with two stop lights. She can cite what her adoption decree declared her parents had done: they “do hereby bestow upon said minor child equal rights, privileges and immunities with children born in lawful wedlock.”

That was not true, but she only learned that later.

“That’s why I joined the military. I felt so lucky to be an American, ironically. I wanted to thank this country for raising me,” she said. “I didn’t think about citizenship because I felt I was being more American than most Americans.”

She excelled in the military, but wasn’t eligible for certain security clearances. She's wanted to serve as a linguist, but couldn't. After leaving, she laid low, terrified of deportation. When Trump won election in 2016, she felt a fear more intense than the night before she deployed to Iraq.

Alessi pulled up a photo of Elmquist in 2019, standing behind a podium marked with the seal of the U.S. House of Representatives. Elmquist was wearing her military uniform, and Alessi recalled that the room went quiet, all you could hear was the “click click click” of cameras.

Elmquist remembered what she’d said: “I fought for my country, now it’s time for my country to fight for me.”

It didn’t.

That session, the bill didn’t pass.

Elmquist was rejected multiple times by immigration. Finally, she made it to an interview, and had to prove she could read and write English. Her interviewer was a veteran, like her, and said it seemed weird she was there. “Tell me about it,” she remembers responding.

She was naturalized in 2022, the day before her 40th birthday. She likes to look back at her picture on the front page of the local newspaper.

“I can see how happy I was,” she says. “I almost cried.”

“I can imagine,” Buttons responded.

She smiled, and wiped away a tear, imagining that one day maybe she’d feel that too.

___

AP researcher Rhonda Shafner contributed to this report.

___

This story is part of an ongoing investigation led by The Associated Press in collaboration with FRONTLINE (PBS). The investigation includes several stories:

Widespread adoption fraud separated generations of Korean children from their families, AP finds

Western nations were desperate for Korean babies. Now many adoptees believe they were stolen

A South Korean adoptee needed answers about the past. She got them — just not the ones she wanted

It also includes an interactive and documentary, South Korea’s Adoption Reckoning.

Contact AP’s global investigative team at Investigative@ap.org.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.