A.C. Nielson

Axtel Carl Nielson lived in Cape Girardeau for 25 years, from the 1910s to 1930s, with his wife Josephine and son Richard. The couple was married in Chicago in 1905 and had at least two children prior to moving to Missouri. During his time in Cape Girardeau, he worked as an auditor for Harrison Securities Inc. ...

Axtel Carl Nielson lived in Cape Girardeau for 25 years, from the 1910s to 1930s, with his wife Josephine and son Richard. The couple was married in Chicago in 1905 and had at least two children prior to moving to Missouri.

During his time in Cape Girardeau, he worked as an auditor for Harrison Securities Inc. and other companies. He was heavily involved in the local community through organizing the Boy Scouts and Salvation Army. During the outbreak of World War I from 1917 to 1919, he served as quartermaster sergeant in the 7th Separate Company and later Company A, 2nd Separation Battalion in the Missouri Home Guards.

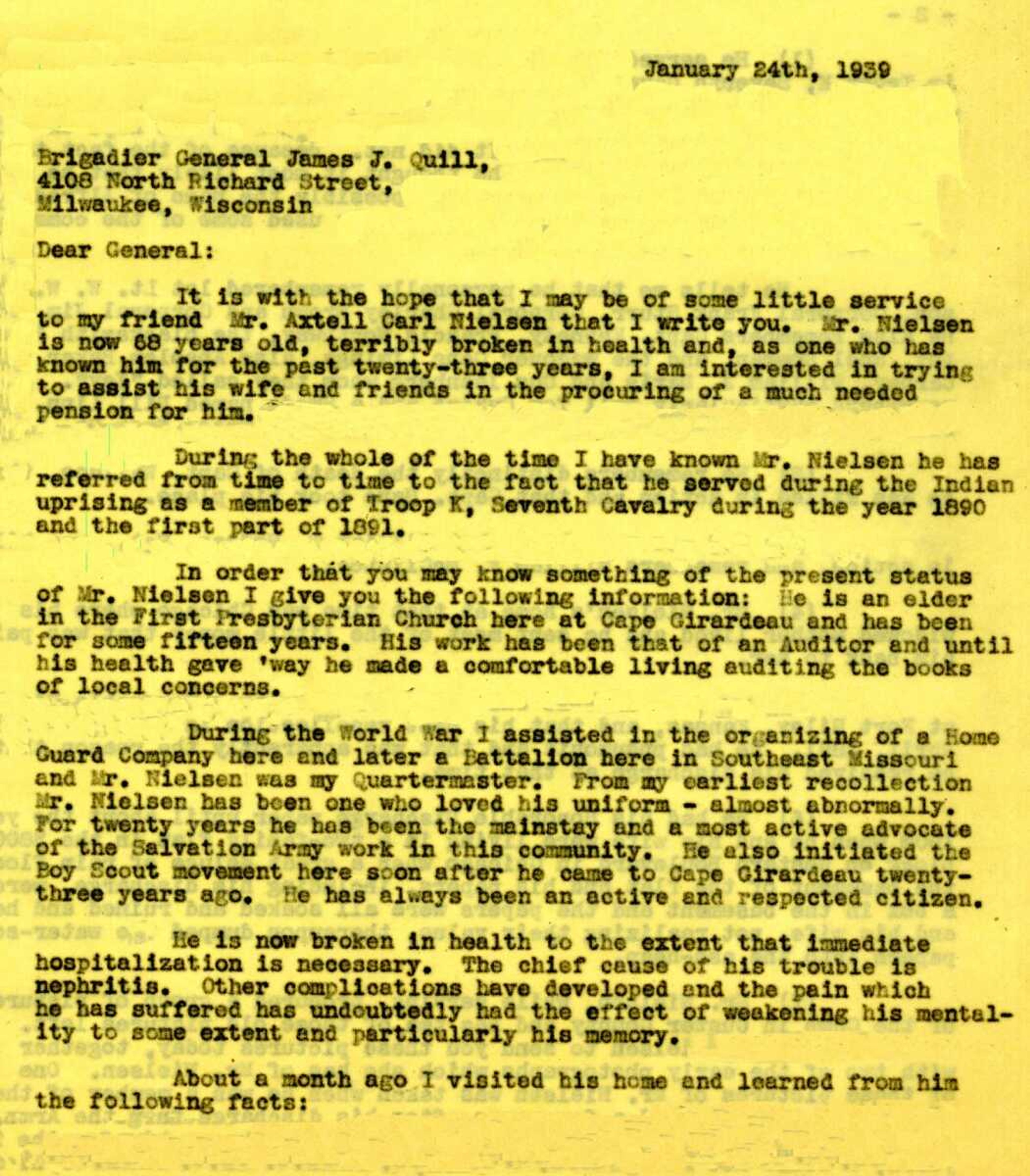

In 1938, word reached attorney Allen L. Oliver from George H. Sutherland of Memphis, Tennessee, that Nielson was in declining health, and he was trying to obtain a pension and admittance to the Army and Navy Hospital in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Complicating matters was Nielson's claim he had served as a teenager in the 7th Calvary in Troop K, under an assumed name, but he could no longer remember which name he used. He may have gone by James Christianson or Alfred Matthis. Nielson was born on Feb. 3, 1871, in Denmark and immigrated to the United States, ending up in Chicago when the Indian Wars out west were occurring. According to him, he enlisted at Fort Omaha in Company E of the 2nd Infantry. He was transferred to Troop K at Fort Riley, Kansas. The troop participated in the tragic engagement with Big Foot's band of peaceful Lakota Sioux along Wounded Knee Creek on December 29, 1890. The Native Americans lost at least 250 men, women and children. Nielson was later discharged at Fort Riley because of pneumonia in April 1891.

Correspondence among Julien N. Friant, James Quinn (who served in Troop K), Oliver and Sutherland attempted to determine if Nielson was telling the truth. After several letters with Nielson's wife, and a personal visit, Oliver unequivocally believed the man did serve. Through his wife, Nielson remembered several names of his comrades in Troop K, including the name of his captain who had been killed at Wounded Knee. Oliver wrote tirelessly in hopes of obtaining a pension for him as he felt he had earned it.

A letter from Quinn, who personally knew Christianson after the war, stated he had attended his funeral in 1930. Both Christianson and Matthis, according to the government, received a pension, and Matthis died in 1900. It may never be known if Nielson did serve without further documentation being uncovered. From the rest of the correspondence, it does not appear he received his pension. His health continued to deteriorate, and he died in Little Rock, Arkansas, on Jan. 11, 1940.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.