Hunter brothers take flying where few could follow

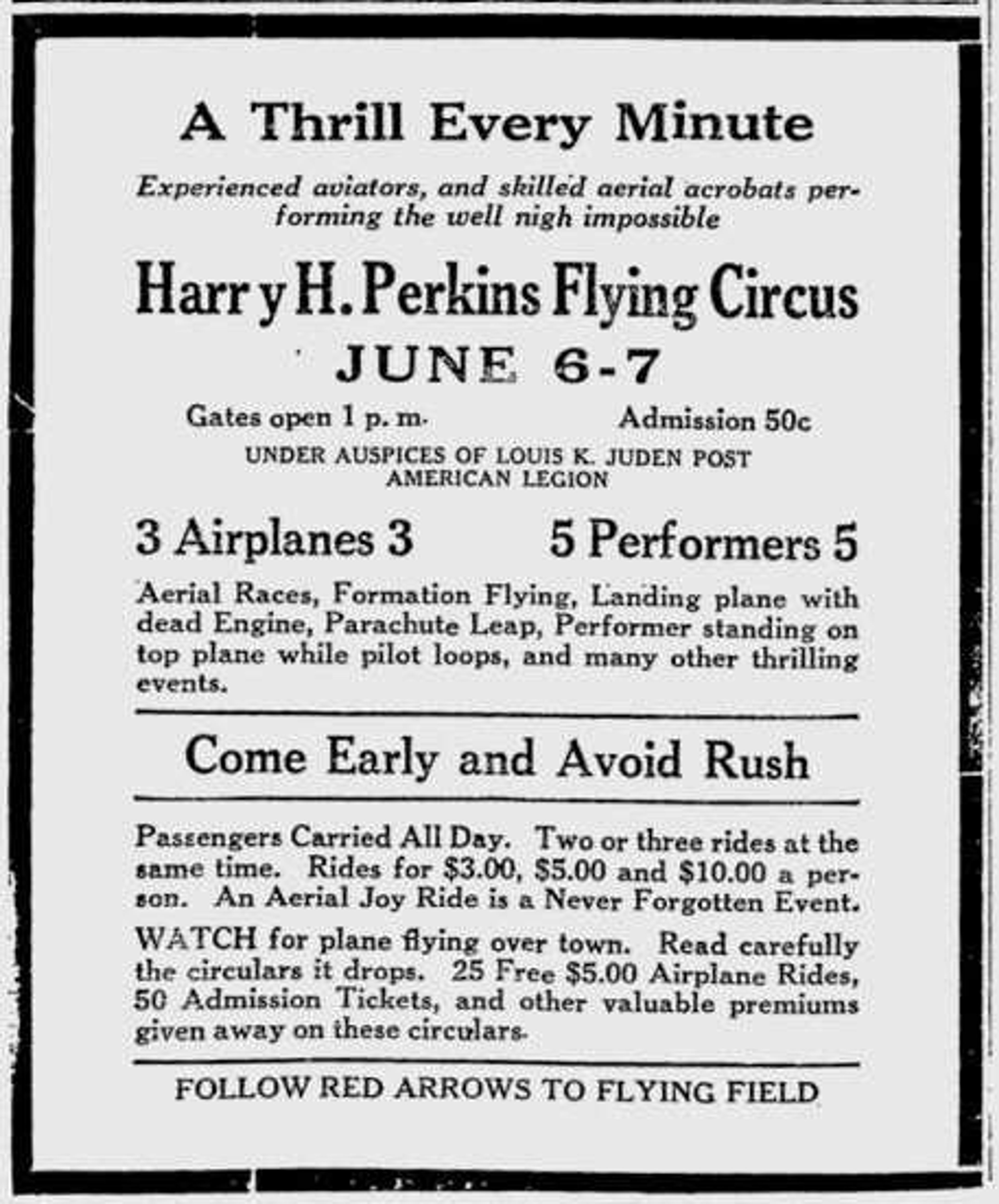

An advertisement proclaimed "A Thrill Every Minute" when the circus came to Cape Girardeau on June 6 and 7, 1925. This was no ordinary circus, however. This was the Harry H. Perkins Flying Circus featuring dare-devil pilots performing aerial stunts and taking passengers on joy rides...

An advertisement proclaimed "A Thrill Every Minute" when the circus came to Cape Girardeau on June 6 and 7, 1925. This was no ordinary circus, however. This was the Harry H. Perkins Flying Circus featuring dare-devil pilots performing aerial stunts and taking passengers on joy rides.

The star attraction was the Hunter Brothers -- Albert, John, Kenneth, and Walter -- who hailed from Sparta, Illinois. They had cut their teeth on motorcycle stunts, but in 1923 decided on a whim to sell their motorbikes and purchase a biplane in St. Louis. After only 90 minutes of instruction, John Hunter was able to fly the plane back home, albeit with a rough landing.

Taking lessons from a local pilot, Bud Gurney, the four brothers quickly became adept at stunt flying. They performed as the Hunter Flying Circus, an act described as "sky vaudeville." By 1925, the brothers had joined the Harry H. Perkins Flying Circus.

At the time, Cape Girardeau didn't have an airport, so the event organizers had to scout for a location. Initially they selected a field along the Cape-Jackson road, but then switched to what they thought was a better location on the Gordonville road west of Cape.

As a publicity gimmick, circulars were dropped from the air in the days prior to the event. Some contained hidden tickets for free admission or airplane rides.

In a front-page story, the Southeast Missourian described the stunts that the troupe would perform: "parachute leaps, tail spins, races, changing planes in mid-air, nose dives, and wing-walking." The story noted, "Kenneth Hunter performs by hanging by his teeth to a rope attached to the chassis of a speeding plane. As an emergency measure an ambulance, ready for immediate action, is kept at the field."

The newspaper offered a prize to the first couple who agreed to get married while airborne during the event. Glover Gill and Emma Scharf decided to participate in "what is said to be the first aeroplane wedding performed in Missouri."

During the opening day of the circus, the couple took to the air along with Rev. H.C. Hoy, pastor of Centenary Methodist Church. With the motor idled at 3,500 feet, the couple exchanged vows and rings before returning safely to a cheering crowd of 350 onlookers.

Watching from the ground, Rev. Hoy's wife was rather anxious about the whole thing. She had good reason to be worried about the dangers of airplane stunts. The following day, the circus was marred by a horrendous tragedy.

Two young women, Grace Lamer and Pearl Baysinger, had arrived from Cobden, Illinois, to attend the show. They decided to buy tickets for a "pleasure trip." Immediately after takeoff, pilot John Hunter lost control of the airplane. It careened into a tree and tumbled to the ground. Hunter was able to jump to safety, but the passengers, riding in the front cockpit, were caught in an inferno and burned to death.

In testimony given to the coroner, the pilot explained that the takeoff was fine, but "as I started to swerve the ship to the right to avoid the tree, it refused to turn. I don't know what it was. The controls might have jammed or we might have hit an air pocket."

He added, "As the plane's wing struck the tree, I immediately shut off the gas and killed the motor. All I remember is that it swung sharply around, hesitated for a moment and then plunged to the earth."

Despite the disaster, the flying circus continued the rest of the day. The organizers didn't want to upset anybody who had traveled a long distance to attend. Ticketholders were offered refunds, but many elected to go forward with their airplane rides.

Prosecuting Attorney Frank Hines immediately opened an investigation into the crash. The Southeast Missourian reported, "The case is unprecedented in Southeast Missouri, and Prosecuting Attorney Hines explained there is no definite state law covering an accident in an airplane. However, he indicated that if there is evidence to show that the plane was defective, or that there had been evident carelessness on the part of the pilot, a general charge of criminal carelessness or negligence could be filed."

The matter was settled two days later when the pilot and the flying circus reached an "amicable settlement" with the families of the victims. John Hunter agreed to pay funeral expenses and $500 cash to the families. He also faced additional financial pain from the loss of his uninsured aircraft, a Standard J-1 biplane built for World War I. It had an estimated replacement value of $3,000.

His brothers Albert and Walter had witnessed the crash. This may have been a factor in the decision by the brothers to ease into the slightly less risky career of flying airmail routes around the Midwest.

Nevertheless, the brothers decided in 1929 to try a new dare-devil adventure: beating the world record for endurance flight. The plan was for John and Kenneth to pilot a plane, keeping it aloft for the most consecutive hours. Walter and Albert would fly a second plane, periodically delivering fuel, food, and clean laundry.

Their first attempt lasted 264 hours, but was thwarted by thick fog that prevented making contact with the refueling plane, forcing a premature landing. In 1930, they tried again. Flying over Sky Harbor Airport near Chicago, the brothers were able to set a new record time of 553 hours, 41 minutes, and 30 seconds in the air -- more than 23 days.

When they finally landed, they were greeted by a massive crowd of 75,000, and found themselves in the midst of worldwide acclaim.

Their endurance record held until 1935. John Hunter didn't live to see the record broken, however. He died in 1932 while traveling to Louisiana to establish an airmail route. While preparing to take off from Rosedale, Mississippi, he was struck by a propeller and thrown into the Mississippi River.

Two of the other brothers had lengthy aviation careers. Kenneth worked as a test pilot for Lockheed, and then later as a corporate pilot. In 1974, he was killed in a crash during a landing approach at Oklahoma City, an incident that was later blamed on pilot error.

Walter worked as a pilot for American Airlines, retiring in 1966. Albert, however, switched to more grounded careers in farming, trucking and moving houses.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.