STEAM Club members learn about earthquakes, structures in innovative fashion

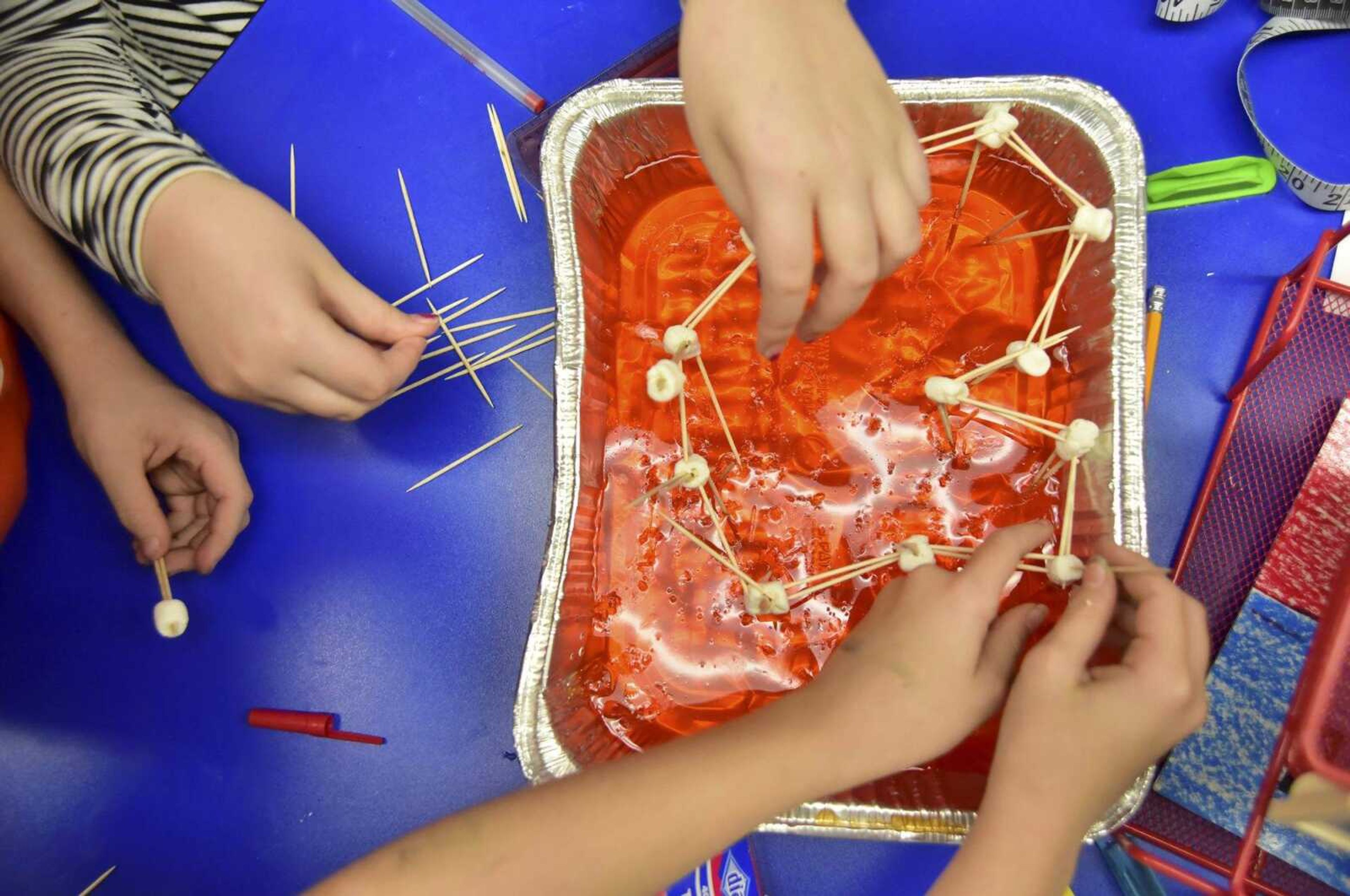

It sounds like a recipe for disaster: pans of Jell-O, marshmallows and toothpicks in the hands of third- through sixth-graders. In reality, it was a lesson in how to avoid disaster. The after-school project, led by Alma Schrader teacher Rhonda Young, was providing insight into how best to construct a building to withstand an earthquake, and the students were attempting to build structures with marshmallows and toothpicks that ultimately could withstand the jiggles of the Jello-O...

It sounds like a recipe for disaster: pans of Jell-O, marshmallows and toothpicks in the hands of third- through sixth-graders.

In reality, it was a lesson in how to avoid disaster.

The after-school project, led by Alma Schrader teacher Rhonda Young, was providing insight into how best to construct a building to withstand an earthquake, and the students were attempting to build structures with marshmallows and toothpicks that ultimately could withstand the jiggles of the Jello-O.

For the full 90 minutes, the group, called the STEAM Club, passed on an appetizing after-school snack and instead contemplated the challenge, confronting problems and developing solutions as they attempted to follow Young's guidelines, which called for a structure 6 inches wide and 12 inches tall.

They had started the Tuesday session with a video on the cause of earthquakes -- the movement of tectonic plates below the earth's surface -- and then were given a worksheet that focused on a strategy before being allowed to go to the cafeteria.

"I can't let anybody get Jell-O until I see some plans," Young said above the din as anticipation built among the group.

The club, an acronym for Science, Technology, Engineering, Art and Mathematics, has met weekly since the start of the school year and has tackled such projects as constructing zip lines to transport Ping-Pong balls, building pyramids out of sugar cubes and fooling with ingredients of homemade silly putty to adjust elasticity.

Young looked at the building plans and responded, "I'm excited to see some of you remember from some of our other challenges that triangles are ..."

"... the strongest shape," fourth-grader Wyatt Cook said, finishing her thought.

From an educational standpoint, everything but a few buildings was about to go according to plan.

Young patrolled the projects with encouragement, never having to issue a reprimand for misuse of Jell-O.

She stopped to observe fourth-graders Jaxon Knight and Ellana Hale.

While most of the pairings had pierced the toothpicks directly into the Jell-O, they pushed the marshmallows below the surface and then inserted toothpicks.

"I think you're the only ones using the marshmallows as an anchor," Young said. "I like that idea."

They also were using a double-toothpick approach, which they credited to Jude Class, who was working at the next table over with fellow fourth-graders Sophia Stuart and Lidia Masters.

It was a structural trend gaining popularity amid a room in search of stability.

Elsewhere, third-graders Kevin Cai and Tyton Hale were pretty much hard at work.

Cai was taking charge. "Would you start helping me and stop eating?" Cai said as Hale fiddled with the marshmallows.

The puffy white pieces soon were put to better use as they used them as anchors after hearing Young applaud the idea.

"It's working; it's getting sturdier," Cai said with excitement. They, too, would employ the double-toothpick approach.

At one point, Young told the students to walk around the room and observe the work of others.

She encouraged the adoption of ideas and even starting over if necessary, noting the trial and errors involved in the inventive process.

"Every time you tear down and start over, you learn what not to do the next time," Young said during the walk-around. "It gets better, better and better."

With the students firmly involved in their task, she took a seat.

"I love the conversations between them," Young said. "They amaze me with their strategies."

Young, who has 18 years of teaching experience, was one of 150 teachers nationwide to be selected to attend the Mickelson Exxon/Mobil National Teacher's Academy for one week last summer in New York.

Currently a fourth-grade teacher, she was one of only two Missouri teachers chosen from applicants for all-expense-paid training in STEAM education strategies, a workshop visited by professional golfer Phil Mickelson and his wife, Amy, who co-sponsor the program.

"It was intense, but I learned so much," Young said.

Every day, she participated in STEAM challenges she could use in a classroom setting.

"The thing that disappointed me is that Cape did not have STEAM in their curriculum," Young said. "A lot of the schools around the country have STEAM labs, STEAM teachers. So I was kind of excited to come back with some of the ideas to put in place."

She said Exxon/Mobil is monitoring the teachers throughout the year, and since she doesn't teach science this year, she started the club.

"My idea was to do this after school and see how it worked," Young said. "And it's just been amazing. The kids -- the conversations are so rich, and the kids are so excited, and they meet the challenges. And if they don't meet challenges, then they just don't want to stop because they want to keep going until they conquer it because they see others conquer it."

Young said Exxon/Mobil targets teachers for grades three through five because of the students' formative stage.

"That's when they get the inspiration and, like, turned on by engineering ideas that later they might go into and improve," Young said. "So they feel like that starts in third to fifth grade, so they invest their money."

Young provides the students with general guidelines and supplies, then steps back and watches as creative thinking takes over.

"They just come up with amazing things -- just amazing things," Young said. "They're engineering, and they don't even realize it."

Young usually conducts the same challenge with a different STEAM group on Thursdays and said she totals 40 to 45 students between the two days.

The group did not meet the week of Thanksgiving, but tales of "Dragon Puppy Puppets" -- using all the parts in a bag to make a toy -- from the previous session two weeks earlier were still in the air.

"It's too fun to be a class," Masters said.

"It's not really a class; it's more like math, like all that stuff, but she's trying to make it, like, into fun projects, which she is doing a very, very good job at," fifth-grader Lucian Nordin said.

In the end, Wyatt's group had assembled a 12-inch structure -- a toothpick stuck in the top to get to the necessary height -- that pretty much withstood the jiggle test.

Others were in various stages, with one resembling more of a Jell-O salad.

The culinary field, rather than engineering, may be in some futures.

But make no mistake: It was no disaster area when the clock struck 5:15 p.m.

Chairs were back on top of desks.

Neat. No sign of an earthquake.

"Every week, we make a big old mess, and every week, we get it cleaned up," Young said.

jbreer@semissourian.com

(573) 388-3629

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.