Thankful People: Moore family counts its blessing after harrowing accident

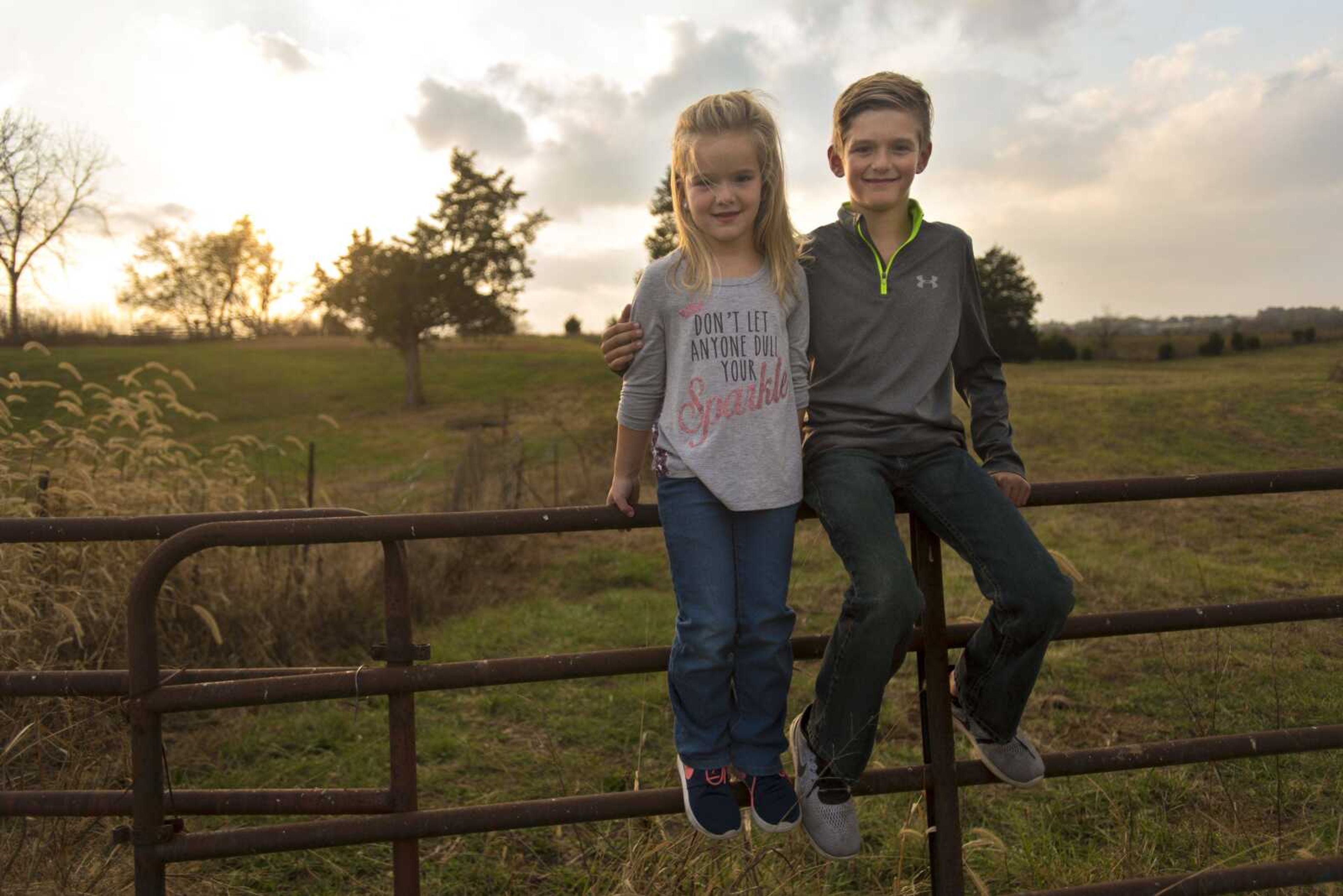

Connor Moore sits at the kitchen counter with his parents in their newly constructed home in rural Perry County. The lean 10-year-old is energetic and inquisitive as his mom, Becky, and dad, Dave, recount the most divinely choreographed day of their lives, one that involved the saving of a life...

Connor Moore sits at the kitchen counter with his parents in their newly constructed home in rural Perry County.

The lean 10-year-old is energetic and inquisitive as his mom, Becky, and dad, Dave, recount the most divinely choreographed day of their lives, one that involved the saving of a life.

Becky, director of the child development lab at the University School for Young Children on the Southeast Missouri State University campus, is talking about CPR, a skill she's been required to be certified in for her job the past 12 years and was called on to use in April, about three months after her latest biennial re-certification.

The wheels appear to be spinning in Connor's head, much like on the motorcycles he's been riding since the age of 3 and racing since 5. He interrupts with an inquiry.

"Could you just, like, do CPR on somebody if they, like, get hurt and you, like, don't know how to do it?" Connor asks.

"No, you have to be able to do it," his mom replies.

Connor asks: "What if nobody knows how to do it?"

The reply is a pensive, uncomfortable look.

The conversation resumes, and after listening some more, Connor takes one more stab: "Mom, so if you aren't trained, do you just let them there?"

He eventually heads off to his bedroom, which has motocross racing trophies -- some as big as him -- and the conversation continues about that April day.

"Had I not done anything and it turned out a different outcome, I knew I never would have been able to live with that," Becky says.

She never had to use CPR on one of the children at work, but she needed it for her own son.

n

It was about 4:30 p.m. April 8, and the Moores were mowing the front field at their not-yet-completed home when Kade Baudendistel, Connor's longtime friend and classmate at St. Vincent de Paul, came running and crying from the field behind the house.

"The first words out of his mouth were, 'Connor's dead and there's nothing you can do,'" Becky says.

The last time she or Dave saw Connor, he was buckled driving their Ranger UTV into the field behind the house. Kade was buckled in as his passenger.

Becky immediately dialed 911, and Dave hopped on his motorcycle to race to the scene, only to be thrown when a wheel caught a hose in the yard. Becky jumped into the car and drove about a quarter-mile behind the house, finding a discolored Connor, with blood trickling from an ear, pinned under the 1,500-pound vehicle.

Connor, all of 4-foot-8 and 70 pounds, had removed his seat belt to better reach the pedals. It was a mistake. He hit an unlevel spot, and the vehicle overturned on its right side, throwing Connor across Kade and out. The roof came to rest across the torso of Connor, who was on his stomach.

"No pulse, no heartbeat, no breathing. Nothing," Becky said.

Becky tried to lift the vehicle, but it wouldn't budge. Dave had abandoned the motorcycle and came running to the scene, lifting the Ranger enough for Becky to slide out Connor to begin CPR.

"I remember doing CPR and just thinking I wasn't going to quit until somebody drug me off of him," Becky says.

That was about 10 minutes later, after she had restored a pulse and first-responders arrived. The time was expedited when neighbors, who were outside and heard Dave's cries for help, rushed to the scene and went to the road to direct emergency personnel.

An ambulance arrived, then Air Evac, which needed just 17 minutes to reach Children's Hospital in St. Louis.

Becky had heard a mushy sound when applying CPR and knew there was something wrong with Connor's lungs. She was right, noting in hindsight both his lungs had collapsed.

"He was basically suffocating," Becky says. "There was nowhere for the air to go. In the helicopter, they decompressed his chest."

Two holes were made in his chest to allow the air to get out, and his blood pressure began to rise.

On the ground, the Moores were traveling at 100-plus mph up Interstate 55. They received updates from her sister, who had been in St. Louis and arrived at the hospital before Connor.

Becky says her sister repeatedly called asking how far they were from the hospital.

"I took that as they wanted to tell us that he didn't make it," Becky says.

On the fourth call, Becky asked why, and she was told they were prepping Conner for a CAT scan.

They covered from Perryville to the hospital in 43 minutes in her parent's car, and the waiting room quickly filled with family. A chaplain entered and prayed with all before Becky and Dave headed up to an intensive-care waiting room. There they met the surgeon in charge of Connor's team of doctors.

Connor had sustained two fractures to a pair of vertebrae, had a fractured pelvis, severely damaged his lungs and had a concussion.

In relative terms, that was good news. The doctor said Connor's heart and brain had avoided damage.

"Actually, the night we got there, he told me, 'I'm confident that your boy is going to be OK. With the injuries we can see ... things can change, but with the injuries we see, I'm confident your boy is going to be fine,'" Dave says about the news he received about 9 p.m.

"I gave him a humongous hug," Dave says.

Connor was on medication and still unconscious at the time.

Kade visited Connor on Sunday and got a squeeze of the hand from his friend. He was the first to get a response.

"That was a good reassurance for Kade to know that he was going to be OK," Dave said.

Connor didn't open his eyes until Tuesday, finally giving his mom the reassurance that all was going to be well.

"He opened his eyes and looked at me, and I said, 'Where's your mom?' and he moved his eyes and looked at her," Dave says. "And I said, 'Where's your dad?' and he looked back at me."

Dave knew Connor was processing information, and all doubts were removed when the breathing tube later was removed, allowing Connor to talk.

"One of his first questions was asking if Eli Tomac won, his favorite dirt-bike racer," Dave says with a laugh. "I was like, 'I think he's OK.'"

Connor, who received loads of cards from his classmates, was released from the hospital Friday.

When the family returned, they found neighbors, community members, family and friends had finished the remaining work on the house.

Connor would miss about a month of school, ultimately finishing third grade with half-days.

It hasn't hindered him as a fourth-grader. If anything, Connor is doing better in school, which Becky credits to both teachers and administration.

"He's doing phenomenal," Dave says. "He's on top of everything. I'm like, 'Holy cow.'"

Connor went through some counseling, something which Becky still is receiving.

Becky says the incident has changed the family dynamics.

"We really don't sweat the small stuff anymore," she says. "It's really changed how we view a problem. ... Our patience level is a lot better."

The family will spend Thanksgiving with Dave's family in their new home, which has remained a positive place to live and dream.

"If it had gone the other way, we wouldn't be sitting in this kitchen right now," Dave says. "I could tell you that."

Becky says she looks back on the whole day as if it was planned.

"Like, weird things happened all day," she says. "Like, how is that not a sign? People were in the right place at the right time."

Dave says Kade's part was pivotal. He lives next door to Becky's parents, who the Moores were living with at the time, and made a split decision to come out to the property. He kept his belt on and was quick to summon help. He receives tight hugs whenever he visits.

"He's my hero," Dave says. "Every time I see him, 'What's up, little hero?' He just kind of grins at me."

Becky is trying to team up with Air Evac to put on a CPR class in an attempt to give back and help others.

"This went out all over," Becky says. "The amount of people that prayed and went to the church, were in churches when we were even on our way to St. Louis. Just the amount of people that prayed and sent stuff and visited and helped finish this so we could move in. There's not enough words to say how thankful we are and how blessed we feel."

jbreer@semissourian.com

(573) 388-3629

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.