Ahead of the curve

Cara McElmurry, Jessica Bailey and Tyler Terry will graduate from Central High School in less than four months. Next year, junior Derek Walker will receive his diploma. The four students are well aware that Central's graduation rate has been low in the past for black students. Of the black freshmen who entered the high school four years earlier, 59.3 percent graduated last spring, according to the school district's report card from the state's education agency...

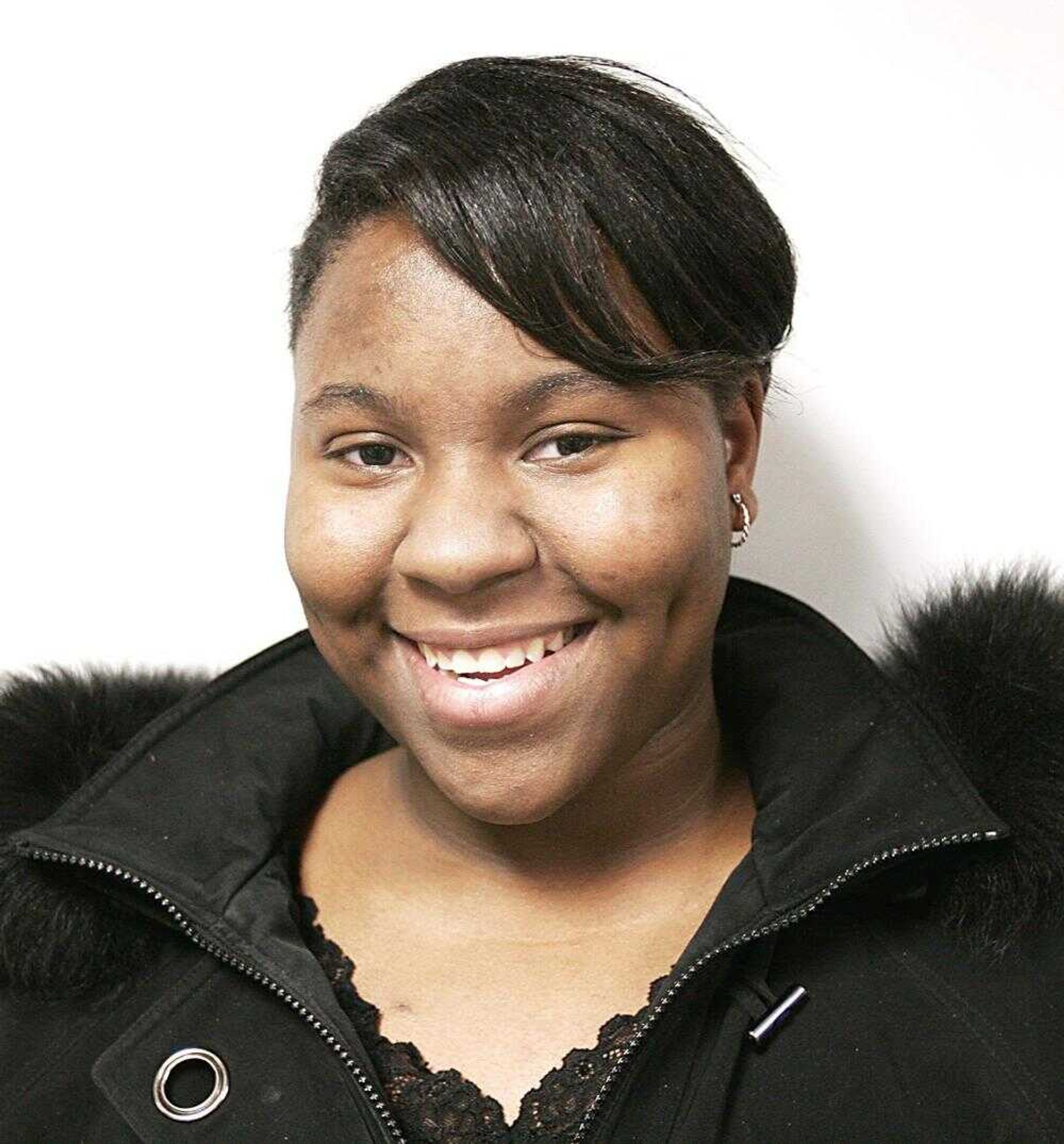

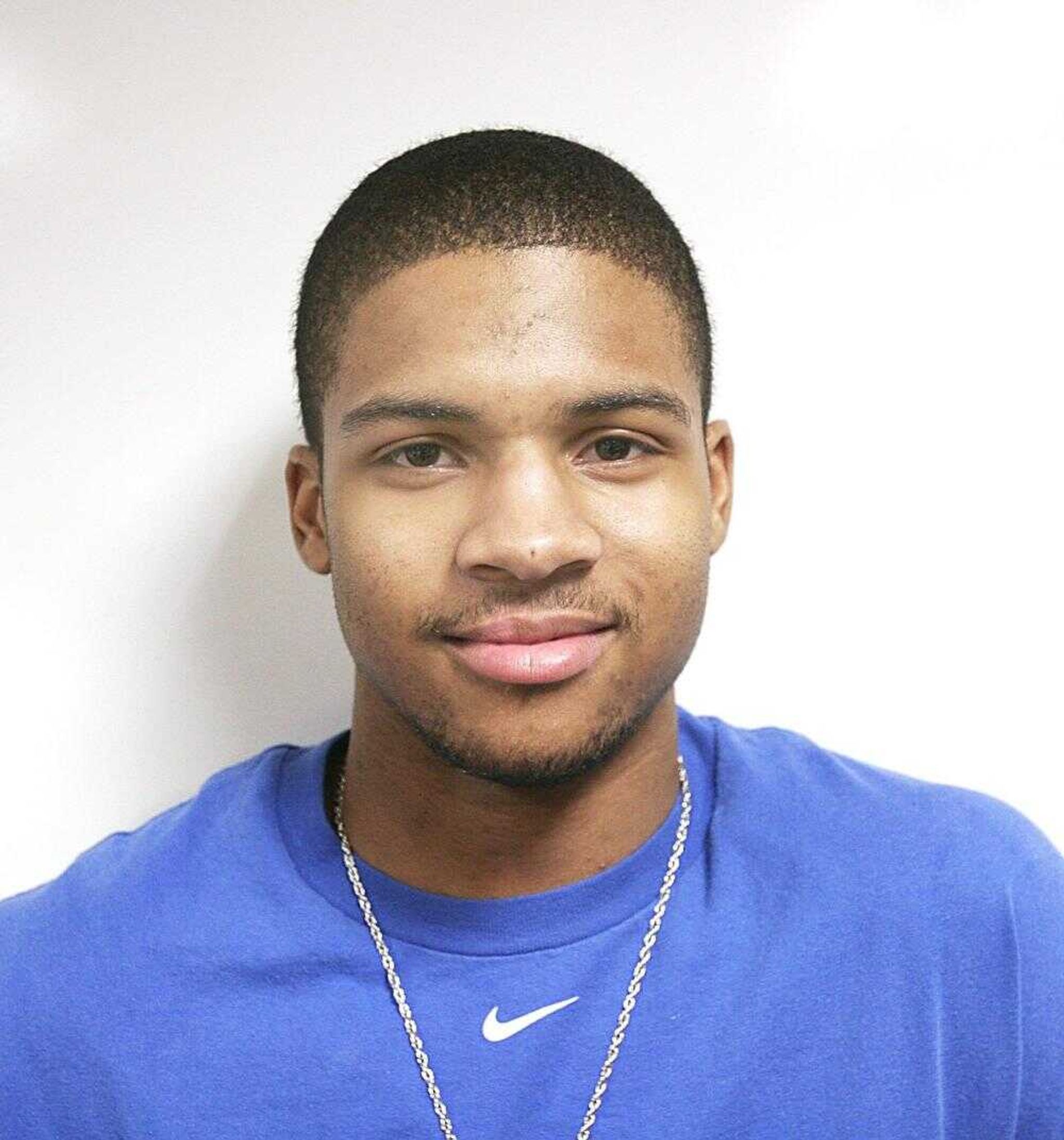

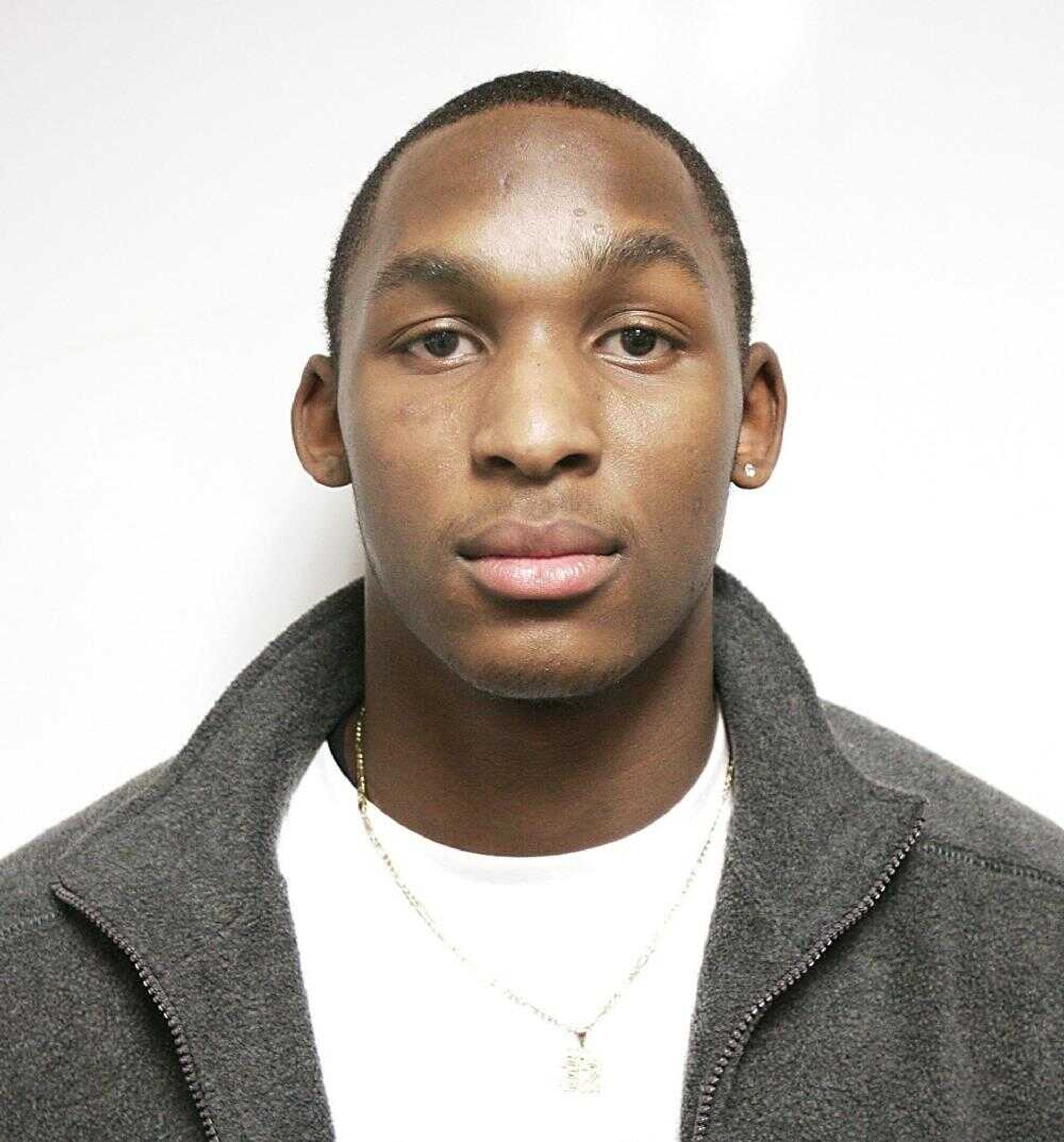

Cara McElmurry, Jessica Bailey and Tyler Terry will graduate from Central High School in less than four months. Next year, junior Derek Walker will receive his diploma.

The four students are well aware that Central's graduation rate has been low in the past for black students. Of the black freshmen who entered the high school four years earlier, 59.3 percent graduated last spring, according to the school district's report card from the state's education agency.

Everyone in McElmurry's family has graduated from high school. Family encouragement is what motivates her to do well in school, she said.

"Education has always been a real big thing for us," McElmurry said. "I think what happens to a lot of black students is that they don't have support from their families."

Terry agreed. "Some parents don't care or don't know what their children are doing after school," he said. "The parents don't push their children to do well."

Each of the students has known a fellow classmate who's dropped out of school.

They believe some students drop out because their friends did, or some will drop out because they were sent back and forth between the regular and alternative school.

"Some people I've known were kicked out of school at one time, and they say, 'forget it,' and just don't show back up," Walker said. "Most of them are on the corner now, selling (drugs) and doing what they can to get by."

The group of students is also familiar with a long-standing achievement gap between black and non-black students on state tests like the Missouri Assessment Program. The disaggregate results of the MAP tests, which are broken down by gender, ethnicity and learning disabilities, show black students' scores are significantly lower.

"I did as best I could on the MAP test," said McElmurry, who was required to take the test for the final time in 10th grade. "I do think there's a lot of people who don't try hard because they're not getting anything out of it."

McElmurry said her mother has always pushed her to do the best she could during school

"Fortunately, my best has always been all A's and B's," said McElmurry, who plans to attend St. Louis University in the fall and major in pre-medicine. Eventually, she wants to become a children's pediatrician.

!["I think it's [racism] something we've all experienced. But once we got to high school and everyone came together, it kind of mellowed out." (Central High School senior Cara McElmurry.)](https://public-assets-prod.pubgen.ai/brand_a7b06a8b-02b9-4920-9426-9b9be1d4e410/asset_bec8b761-b0f5-52c9-9211-b588f6a160da.jpg?w=2048)

Bailey, who grew up in St. Louis, moved to Cape Girardeau in the eighth grade. She's seen what could happen if she doesn't get an education.

"The area in St. Louis where I grew up at wasn't too good of a neighborhood. There were gangs, and the police would come to the area every night," Bailey said. "A week before we moved away from St. Louis, there was a dead body behind the trash can of our house."

Bailey's mother motivates her to do well in school. After she graduates, she plans to attend college to become a homicide detective.

Both Walker and Terry said sports motivate them to maintain good grades.

"I need to do well in school or else I can't play sports," said Walker, who plays on the high school's football and basketball teams.

The students have significant role models in the black community that they look up to. For Terry, it's Mohammad Ali, and for Walker, it's Michael Jordan and Kobe Bryant. Locally, McElmurry said Debra Mitchell-Braxton, founder of the city's annual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. memorial breakfast, is one of her role models.

It's these black figures who have helped the students learn to ignore the racism that they say still exists.

"Some of the parties we can't go to," Walker said. "You pull up to a party and someone will say, 'no black people allowed.'"

Terry said players from opposing teams call Central's black players racist names during football games. "There's a lot of tension when you play against the predominantly white schools in football," he said.

"I think it's something we've all experienced," McElmurry said. "But once we got to high school and everyone came together, it kind of mellowed out."

jfreeze@semissourian.com

335-6611, extension 246

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.