WASHINGTON — Space shuttle science may soon come to an eye doctor near you: Researchers are using a NASA gadget to finally tell if a cataract is brewing before someone's vision clouds over.

It's a story of shot-in-the-dark science that paid off with a noninvasive test that detects when eyes are losing the natural compound that keeps cataracts at bay.

Any eye doctor currently has the equipment to detect cataracts, said Dr. John Kinder, an ophthalmologist with Eye Consultants in Cape Girardeau. Some studies have shown that smoking and sun exposure accelerate the formation of cataracts, but "at this point there haven't been any vitamins or medicine that will prevent a cataract," he said.

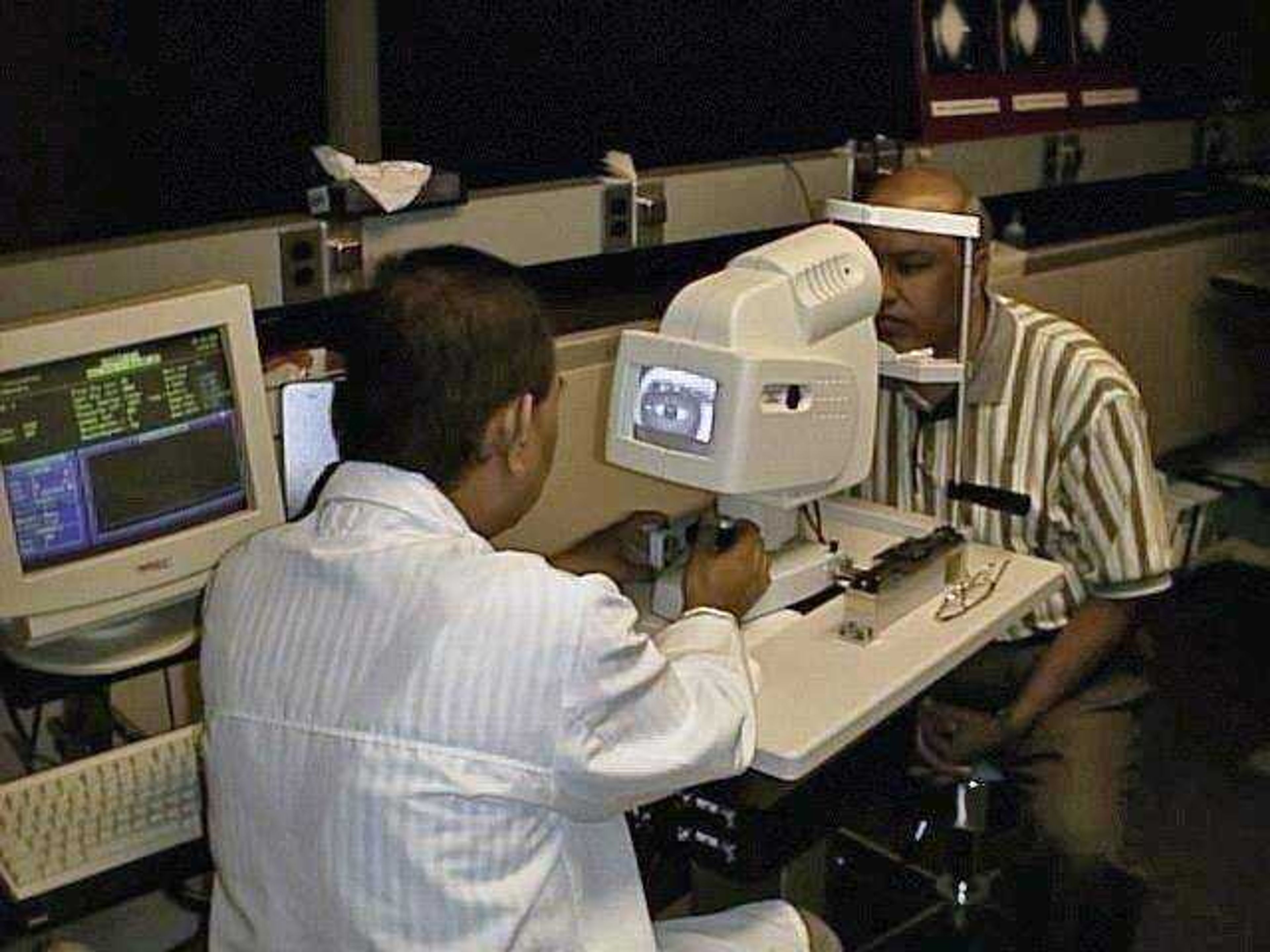

Enter the NASA device. It allows easier testing of whether certain medications might prevent or slow cataract formation.

Don't call the eye clinic yet: The government has only a few prototypes of the device and no commercial manufacturer lined up. But already, doctors at Baltimore's Johns Hopkins University have begun experimental use to see how the exam might fit into the care of a variety of eye patients.

"It's like an early alarm system," said Dr. Manuel Datiles III of the National Eye Institute, who led a study of 235 people that found the laser light technique can work.

It all started when NASA senior scientist Rafat Ansari developed a low-powered laser light device to help astronauts with experiments growing crystals in space. Ansari, with NASA's John Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, knew physics, not medicine. Then his father developed cataracts, where the eye's normally clear lens becomes permanently clouded.

Kinder said early on, glasses can help, but "as the cataract worsens, glasses no longer help and surgery becomes necessary to improve the vision," he said in an e-mail.

Ansari read up on cataracts and learned the lens is largely made up of proteins and water. One type of protein, called alpha-crystallin, is key to keeping it transparent. When other proteins get damaged — by UV rays, cigarette smoke or aging — alpha-crystallins scoop them up before they can stick together and clog the lens. We're born with a set amount of alpha-crystallin. Once the supply's gone, cataracts can form.

Ansari's space laser measures proteins that make up crystals. Ever notice the dust particles floating in a flashlight beam? It's the same principle. Small particles flow fast and larger ones more slowly, so that light shining on them scatters in different, measurable patterns.

Could it spot cataract-related proteins? His next step is not for the queasy. Ansari bought some calf eyes at a slaughterhouse and got his then-teenage daughter, now a doctor, to dissect the lenses in their kitchen. He stuck them in the refrigerator to test after the cold clouded them over. (Ansari hadn't known that biologists do just that step to create a model of human cataracts.)

When he warmed up the lenses and beamed his device, light scattering differed with the lens' changing opacity. It was time to ask eye specialists if the technique might allow usable alpha-crystallin measurement.

It took more than a decade of laboratory and animal testing, but the result is a machine that does just that — by aiming Ansari's special laser at the lens for five seconds and then calculating light scattering.

In last month's Archives of Ophthalmology, National Institutes of Health researchers reported tests of 235 people ages 7 to 86. Alpha-crystallin decreased steadily both as lenses began to fog and as people with seemingly clear lenses got older.

"What we are really looking at is the reserve of this alpha-crystallin," Ansari said. It can "repair any damage if there is a certain concentration. If it depletes below that level then I think the game is over."

What next? NASA and NIH researchers separately are planning to study if special formulations of antioxidants — nutrients that fight certain age-related tissue damage — can slow alpha-crystallin loss.

Ansari also plans to measure the effect of long-term space travel on astronauts' vision.

Already, Datiles has used the test to diagnose cataracts beginning in some patients whose doctors found no other reason for their worsening vision.

And at Hopkins, ophthalmologist Dr. Walter Stark is using it to help tell if some patients complaining that their LASIK surgery for nearsightedness is wearing off need more vision-sharpening surgery — or if they're really forming a cataract, which LASIK can't fix. Also, researchers are testing diabetics with a cataract-speeding eye disorder.

"This test does correlate significantly with cataract formation," Stark said. "We think it has great potential."

Features editor Chris Harris contributed to this report.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.