Stormchasers 'in awe of that power'

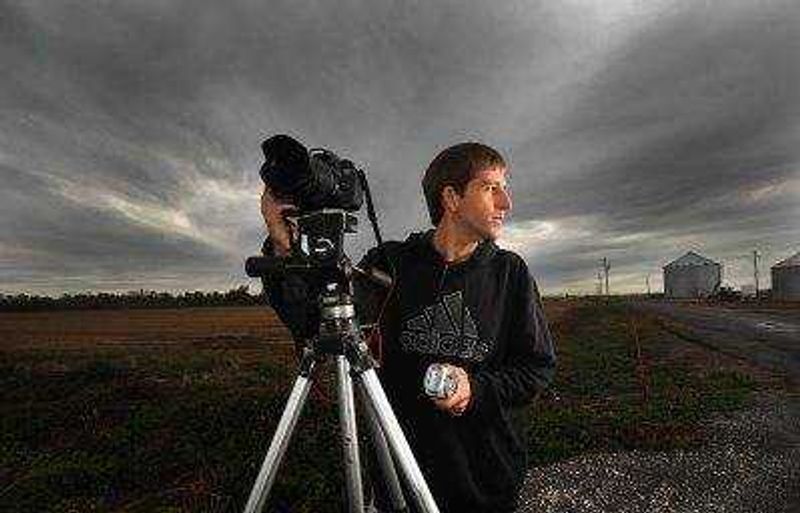

Churning, angry cloudscapes tinged with green and purple; panoramic long exposures crackling with streaks of lightning; it was the pictures that first caught David Patterson's eye. He found himself noticing storm photos in a friend's online gallery about three years ago...

Churning, angry cloudscapes tinged with green and purple; panoramic long exposures crackling with streaks of lightning; it was the pictures that first caught David Patterson's eye.

He found himself noticing storm photos in a friend's online gallery about three years ago.

"I've always enjoyed storms, but I saw these pictures, and I thought, 'Woah! Where'd you shoot that?'" he said. "And he explained that he chases [storms], and I just said, 'Man, I wanna go.'"

So Patterson, already a photographer, went along for the ride.

"I got hooked," he said. "Just Mother Nature and the show she puts on, I guess. If there's one thing [I enjoy most about storm-chasing] it's storm structure and the way it looks being right up in front of it."

Before long, the 34-year-old Cape Girardeau native had his Skywarn severe weather-spotting certification and was plugged in to the underground storm-tracking community.

"It starts with the storm prediction center. They'll outline what the chances are for severe weather, and, if the chances are good, we'll go out a few days to check it out."

He explained that the majority of the chase is done poring over meteorological models and maps in the days leading up to a storm, and nothing's ever guaranteed.

"You get yourself worked up about two days ahead of time," he explains. "You get off work, you find a babysitter, and then there wasn't a tornado after all."

But he says that the feeling of a chase once a storm fires is a rush of the first order. He and the friends with whom he sometimes chases usually stay about a mile to the southeast of a storm cell, navigating gravel roads and farmland in Patterson's Toyota Corolla, jockeying for the prime vantage point.

"Being to the southeast is the No. 1 rule for all chasers. It gives you two modes of escape," he explains. "But a lot of times, the most dangerous part is getting to and from the storms. It's traffic. It's other drivers with their hazards on doing 30 on the interstate."

Not to mention other chasers.

"They call it chaser convergence. There are a lot of people who have a smartphone, and think they're footage junkies all of a sudden," he says. "It started out like that for me but then I realized that I didn't like those type of people; the footage junkies who only care about getting whatever shot they're after."

Because despite the initial draw, Patterson doesn't chase for pictures. He chases to help the weather service.

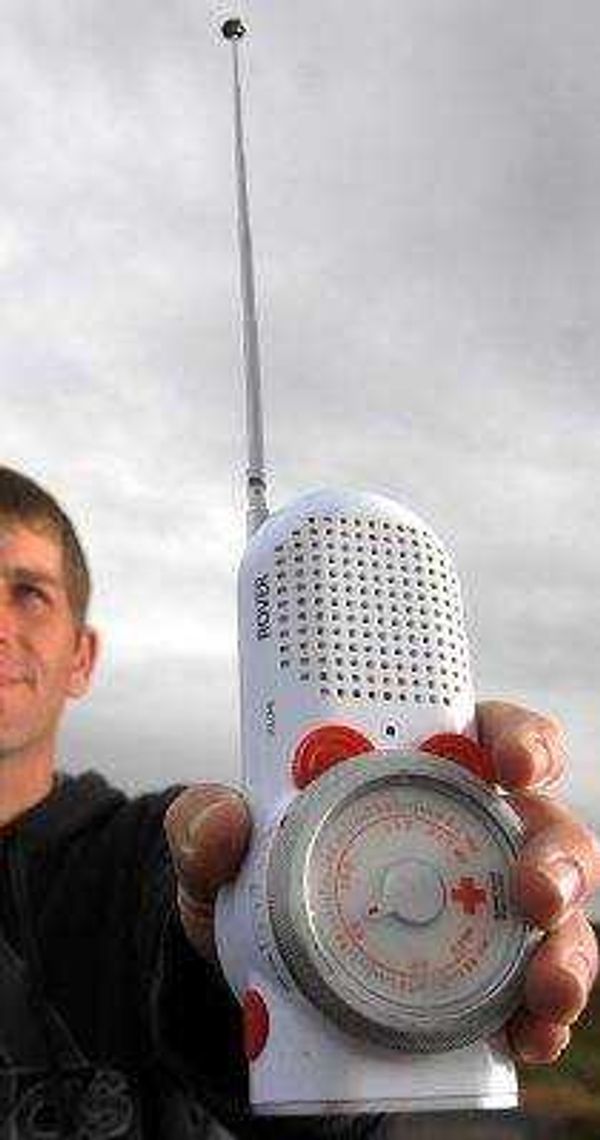

"One of the things that I really enjoy about chasing is, once I know what I'm seeing, I can call in reports while it's going on. Because that's where the meteorologists wish they could be." he says. "Then I shoot damage, piece it all together in my head and then forward everything I got to the weather service."

Stark, sobering and just as powerful as an EF4 itself are the pictures of the aftermath. Sometimes, it's as harmless as a downed tree branch or a toppled play-set in the yard. Other times, it's much darker.

It's a splintered farmhouse, insulation caught in the trees; or a displaced refrigerator, slack-jawed and still reeling in the calm after the storm.

There's a burden to those pictures. Those are people's lives and livelihoods. But since tornadoes are rated based on the severity of damage left behind, it provides researchers with an important data set. Still, Patterson is tight-lipped about those pictures.

"I've never sold a single picture," he says, weary and careful. "I really don't want to make money off of people's misfortune like that."

He says the most satisfying part of any chase is being able to warn people of incoming severe weather.

"Maybe you stop for lunch or gas before things start popping off and you talk with people," he says. "Once, I told probably 15 people at lunch, none of whom knew there was a storm coming. Then that afternoon, you know, we're watching seven transformers blow right down the line. It feels good to be able to give people a heads up."

But then again, there was the EF4 he saw in South Dakota. After years of chasing and more than 100 tornado-less outings, there it was.

"I was just in awe at the time," he says. "It doesn't even appear to be moving. You're just in awe of that power."

Patterson says that while the experience is one-of-a-kind, nobody should underestimate severe weather.

"People should be very careful," he says. "It goes back to storm chasing in general. Common sense goes a long way."

tgraef@semissourian.com

388-3627

---

Twisters by the numbers

166-200: mph of wind in an EF4 tornado

27: Annual average number of tornadoes in Missouri

01: Number of fatal lightning strikes in Missouri in 2013

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.