Missouri citizen scientist has become hummingbird expert

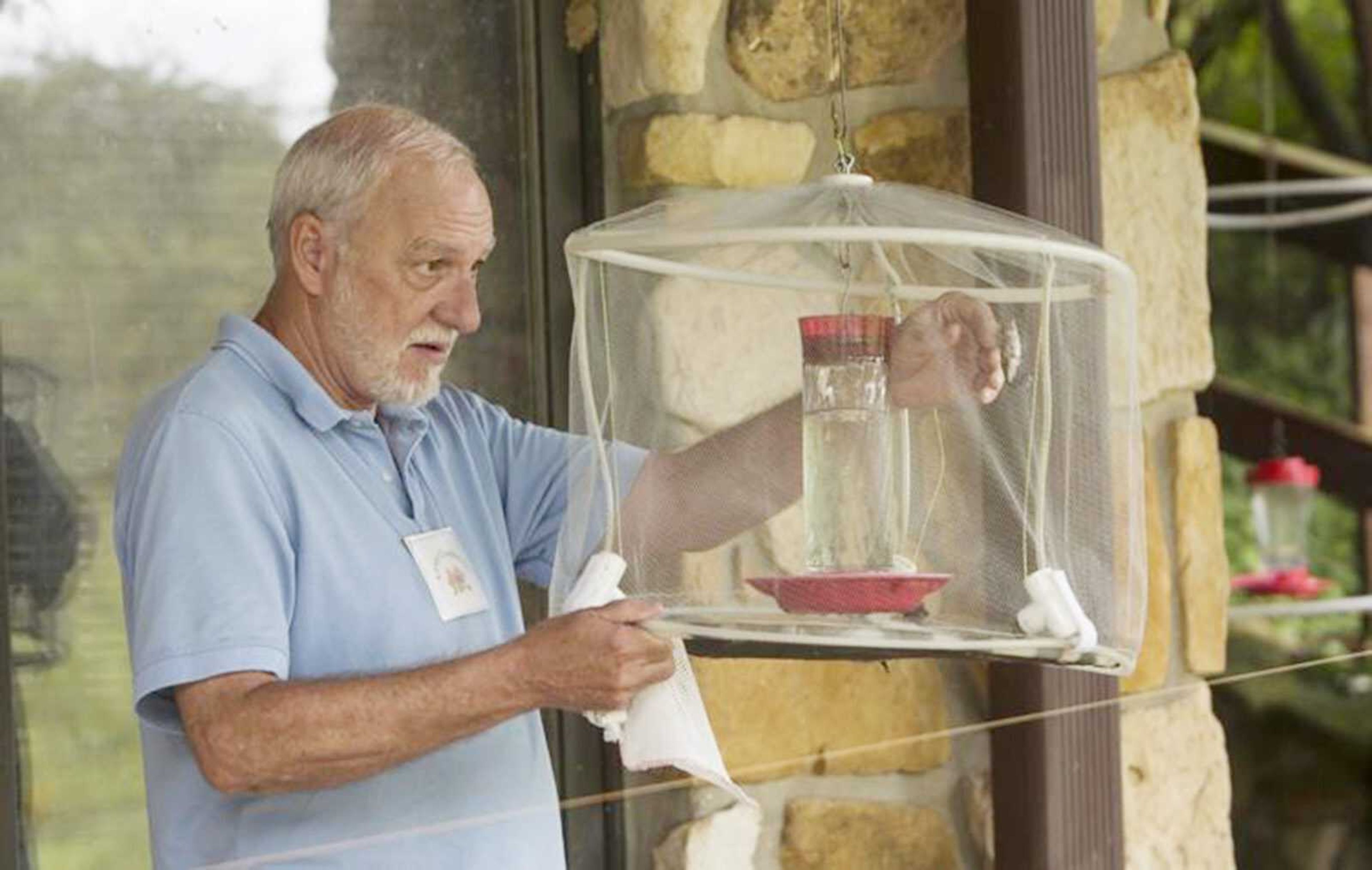

LEASBURG, Mo. -- The ruby-throated hummingbird flitted past the wildflowers at Onondaga Cave State Park toward the feeder full of sugar water and into a trap. It was the first specimen of the day for Lanny Chambers. He pulled the hummingbird out of the netting, put it into a mesh bag and then examined the adult female under lamp light. ...

LEASBURG, Mo. -- The ruby-throated hummingbird flitted past the wildflowers at Onondaga Cave State Park toward the feeder full of sugar water and into a trap.

It was the first specimen of the day for Lanny Chambers. He pulled the hummingbird out of the netting, put it into a mesh bag and then examined the adult female under lamp light. This hummingbird came in at 3.4 grams, about the weight of a penny. Around one of its legs, he fastened a metal ring engraved with an identification number: M41841.

Chambers belongs to a small group of citizen-scientists across the continent who study hummingbirds -- a job that is both laborious and essential as scientists seek to learn more about the migratory bird's role as a pollinator in an era of climate change.

"I don't know of anyone else in the state who's done more research on hummingbirds than Lanny," said Sarah Kendrick, Missouri's state ornithologist.

Chambers, 72, a retired graphic designer from Fenton, said he bands about 400 per year. The vast majority are ruby-throated hummingbirds (Archilochus colubris), the only species known to nest in Missouri.

Because hummingbirds are protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, banding them requires a license from the U.S. Geological Survey's Bird Banding Laboratory. And Chambers is one of 110 people in the United States permitted to do so, said Bruce Peterjohn, chief of the Bird Banding Laboratory. He said another 24 licensees live in Canada.

Ruby-throated hummingbirds, common across the eastern United States, generally winter in Central America before migrating and nesting in North America in the spring.

"We hope that if we band enough birds, we'll catch each other's birds and learn more about their migration travels," Chambers said. "We can make generalizations, but we have precious little data. Hummingbirds are way too small to carry radios."

Chambers and his wife, Linda, first became interested in the quarrelsome birds during a trip to Colorado in the 1980s.

"They're relatively fearless," he said. "They know they can out-fly just about anything else. They're not fast, but they're so maneuverable they're very hard to catch.

"And they're beautiful. Their iridescent feathers catch people's eyes."

Threats to the birds

Chambers has maintained Hummingbirds.net since 1995; until recently, on the site, he plotted the visitor-submitted location and dates of first spring hummingbird sightings.

A 2013 study published in The Auk, the Journal of The American Orinthologists' Union, suggests climate change could affect the relationship between hummingbirds and the plants they pollinate. The study uses data collected on Chambers' site and from the group Journey North.

The study found ruby-throated hummingbirds were arriving in North America about 15 days earlier than they had historically, possibly because of higher temperatures in their winter homes.

The fear generated by climate change is hummingbirds will arrive before a plant blooms, or after it is done blooming.

"It means the birds won't have the food supply that they've come to depend on," Chambers said of the latter scenario, "and for the plants, it means that they won't get pollinated before they stop blooming. So it's not good for anybody."

He noted the birds and plants had "co-evolved over millennia."

The Audubon Society, dedicated to the protection of birds, cites the 2013 study and a separate 2012 study as indicators of climate change effects.

"The degree to which hummingbirds are able to adapt to accommodate these changes is poorly understood," the group says on its website, calling for more research.

Onondaga research

On Saturday, the capture of the adult female shortly after 10 a.m. delighted a crowd of about 20 people who hovered around Chambers as he measured the bird. Missouri State Parks hosted and advertised the event.

Chambers placed the bird in 9-year-old Brayden Bostick's flat palm. It stayed still for several seconds. Then, it was off.

Chambers asked Brayden if he felt the bird buzzing in his hand. That was its heartbeat, Chambers said.

"I was actually kind of freaked out," said Brayden, of Leasburg. "It scared me."

Chambers said Labor Day weekend was peak migration season for the species, and he suspected Saturday that recent rains signaled to the birds they should leave.

It was one explanation for a slow day catching hummingbirds. Chambers caught two more Saturday morning at Onondaga: an immature male and an immature female.

The immature male was 3.6 grams, which the couple considered heavy.

Chambers said the bird likely had been filling up on bugs to prepare for its flight south.

According to the Missouri Department of Conservation, hummingbirds can lose up to half of their body weight during the trip.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.